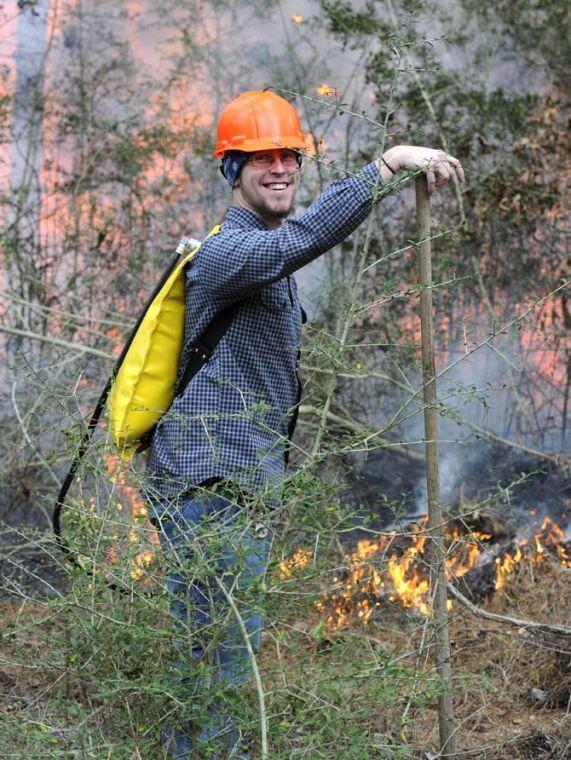

A forest fire protection and use course may sound boring — that is, until it’s revealed that its 10 students get to start fires for a grade.

Niels de Hoop, professor in the Louisiana Forest Products Development Center at the LSU AgCenter, said students in his RNR 4032 class learn not only about preventing forest fires, but also how to use fire as a forestry tool. Prescribed burns can be used to remove competing vegetation, underbrush that blocks wildlife habitats and food and excess fuel material that can ignite during dry weather.

De Hoop’s course lasts eight weeks, during which students typically conduct one to two prescribed burns at the Bob R. Jones-Idlewild research station in Clinton. Prescribed burns generally cover a 10-to-20-acre stand of trees, de Hoop said.

“There’s several firing techniques that you can use,” de Hoop said. “Some are hotter than others, some burn slower than others.”

Days with relatively low humidity and 9 mph winds from the north are ideal for burning, de Hoop said. It is also important to determine how high the smoke will rise and whether it will blow away or smoke the area in, he said.

Forestry and natural resources ecology and management junior Kasie Dugas and forestry senior Dexter Courville said although the course is fun, its value lies in the hands-on experience.

“The class is a good tool to teach you the do’s and don’ts of burning and land management,” Courville said.

Courville said every burn and every stand is different, making for a unique class.

“Cool guys walk away from flames,” said Charles Pell, forestry senior. “We walk through them.”

Because the class only has a couple of chances to do prescribed burns, conditions are not always exactly right, Dugas said. Still, the practical experience gives students the discretion necessary in the industry to know when might be a better day to burn, she said.

Dugas said when she and her classmates finish the course, they will be certified to conduct prescribed burns.

“Once we’re done with the class, we’re pretty much going to know what we need to do and not to do and people can trust us,” Dugas said.

De Hoop said Louisiana has a lot of wildfires, with most ranging in size from 30 to 100 acres. They are small when compared to the “spectacular fires” seen in the American West, he said.

Louisiana’s rainy weather and humidity keeps the risk of fire low, de Hoop said. On the other hand, the humidity is much lower in the dry intermountain West where wildfires often ignite.

De Hoop said because the need in the West is normally to suppress fire rather than prevent it, underbrush and excess fuels collect in some forests, creating a hazard.

“You see stands that are grown up that are just sort of tinder boxes waiting to happen almost explosively, so they’re trying to institute some prescribed burning and fuel reduction,” he said.

But, fuel reduction operations that remove excess branches and limbs are not always economical in the West, de Hoop said.

“It’s very tough for them because there’s not nearly as many sawmills and paper mills in the intermountain West anymore that are able to take this material,” de Hoop said.

By contrast, timber makes up half of Louisiana’s agricultural industry and forestry is the No. 4 employer in the state, he said.

Forestry management is important in Louisiana for a number of reasons, de Hoop said. One is to protect people who live in wooded areas and their structures.

“We have a lot of people that live scattered throughout the woods nowadays, so the reason to put them out has become more intense than in the past,” de Hoop said.

De Hoop said excess materials, such as dead trees and leaves, tend to rot because of Louisiana’s high humidity, so it is not dry enough to burn. Despite the high rotting rate, Louisiana also has a high growth rate that maintains a steady supply of biomass, he said.

“When we do get these dry periods, typically late summer into the fall, we have a lot of material there that can catch fire that’s now dry enough,” de Hoop said.

Southern pine forests have evolved with fire, de Hoop said, making the trees flame-resistant. Because of this, forests in the South are ideal for using prescribed burns to remove underbrush and other excess materials.

However, many foresters in Louisiana fear liability lawsuits and refuse to conduct prescribed burns, de Hoop said. Smoke management is often their main concern, he said.

“If you’re burning and the wind changes and now you’ve smoked in a local town or a local hospital or a local nursing home, or you’ve got somebody in a house nearby … and [he or she] can’t breathe very well in the first place and now you’re smoking them in, you’ve got a big liability situation,” de

Hoop said.

De Hoop said liability concerns have “prevented a lot of prescribed burning from happening that from a forestry standpoint really needed to happen.”

De Hoop said fire is a tricky but effective tool — and only one of many that foresters use to manage land.

“The art of forestry … is taking many, many different things and putting them all together to make it work for the forest.”