The work of a master painter was exposed for the first time yesterday to crowds wielding iPhones, tablets and a wide spectrum of digital cameras.

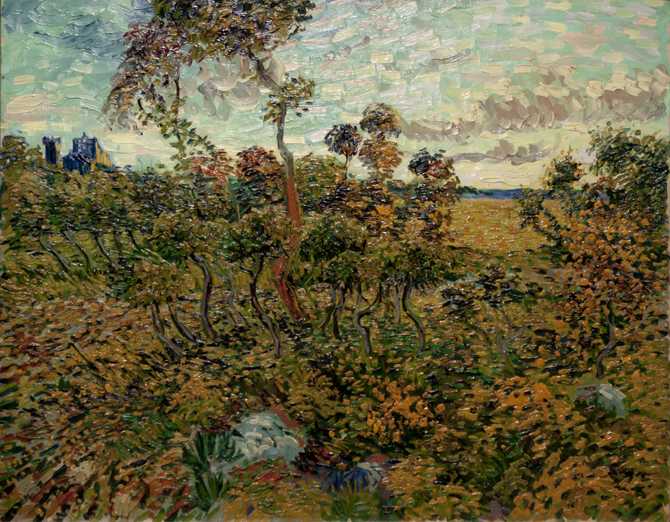

“Sunset at Montmajour” by Vincent van Gogh hung Tuesday on public display at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, where it will continue to pose for a year as tourists and art admirers examine its twisted trunks and light-reflecting leaves.

But while excitement still lingers over the new discovery, critics have described “Sunset” as clumsy, fussy and a failure. Van Gogh himself wrote to his brother 125 years ago that the study was “well below what I’d wished to do.”

Even the wall of words accompanying the museum display acknowledge the brushwork “lacks precision in some places” as a result of the unforgiving terrain.

I found the criticisms unsettling at first. Though I’m an advocate of critical thinking and constructive assessments in art, it doesn’t seem right to belittle the painting for being a transitional piece.

Whether it’s art, sports or skipping rocks, the work we produce in the developmental stages of success is important, even if it doesn’t compare technically to the heights of our eventual peaks.

There’s the artist’s rut, the writer’s block and the player’s slump. Creative wells run dry and ideas evaporate before taking shape. Dreaded dry spells threaten productivity and send uncertainty creeping into our thoughts when things seem to be going well.

It’s the pressure to constantly make masterpieces materialize and the fear of criticism that keeps people from embracing these influential transition periods. What comes after these begrudged phases are the golden ages and the innovative eras that we desire.

Just one month after painting “Sunset” on July 4, 1888, Van Gogh created “Sunflowers.”

“I am hard at it, painting with the enthusiasm of a Marseillais eating bouillabaisse,” Van Gogh optimistically wrote to his brother about the multiple paintings of the flowers. “So the whole thing will be a symphony in blue and yellow.”

In 1888, Van Gogh spent the summer days developing his signature style in the bright sun rays of southern France. He began some of his most famous paintings in this year, leaving behind realism and learning to be an impressionist. He was injecting motion, light and a new color palette into his work.

“Sunset at Montmajour” is an ambitious and experimental piece from this time, but criticisms have described it as somehow less than a worthy work of artistic brilliance.

Christopher Knight, art critic for the Los Angeles Times, called it “blandly pretty.” Jonathan Jones, an art blogger with The Guardian, said it was “just not that wonderful” and an “uncharismatic daub.”

If an unraveling and mentally ill Van Gogh were alive to see these responses, would he have continued painting? Would he have bothered to lay down the tedious strokes in “Starry Night?” Or would he have shot himself that much sooner?

Maybe “Sunset at Montmajour” doesn’t compare to “Cafe Terrace.” It isn’t “Vincent’s Bedroom in Arles,” and it won’t grace as many dorm room walls as “Head of a Skeleton with a Burning Cigarette.”

But the newly discovered painting was worth more as a learning experience for Van Gogh than the tens of millions of dollars of its material value today.

We should similarly value our transitional works as million dollar masterpieces. It’s the slack, the slowdowns and the internal impediments that inspire growth and ripen talent.

Opinion: Transitional works are just as valuable as masterpieces

September 24, 2013

“Sunset at Montmajour” was put on display Tuesday, Sept. 24, 2013, at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum. The painting was declared this month as a genuine work by van Gogh.