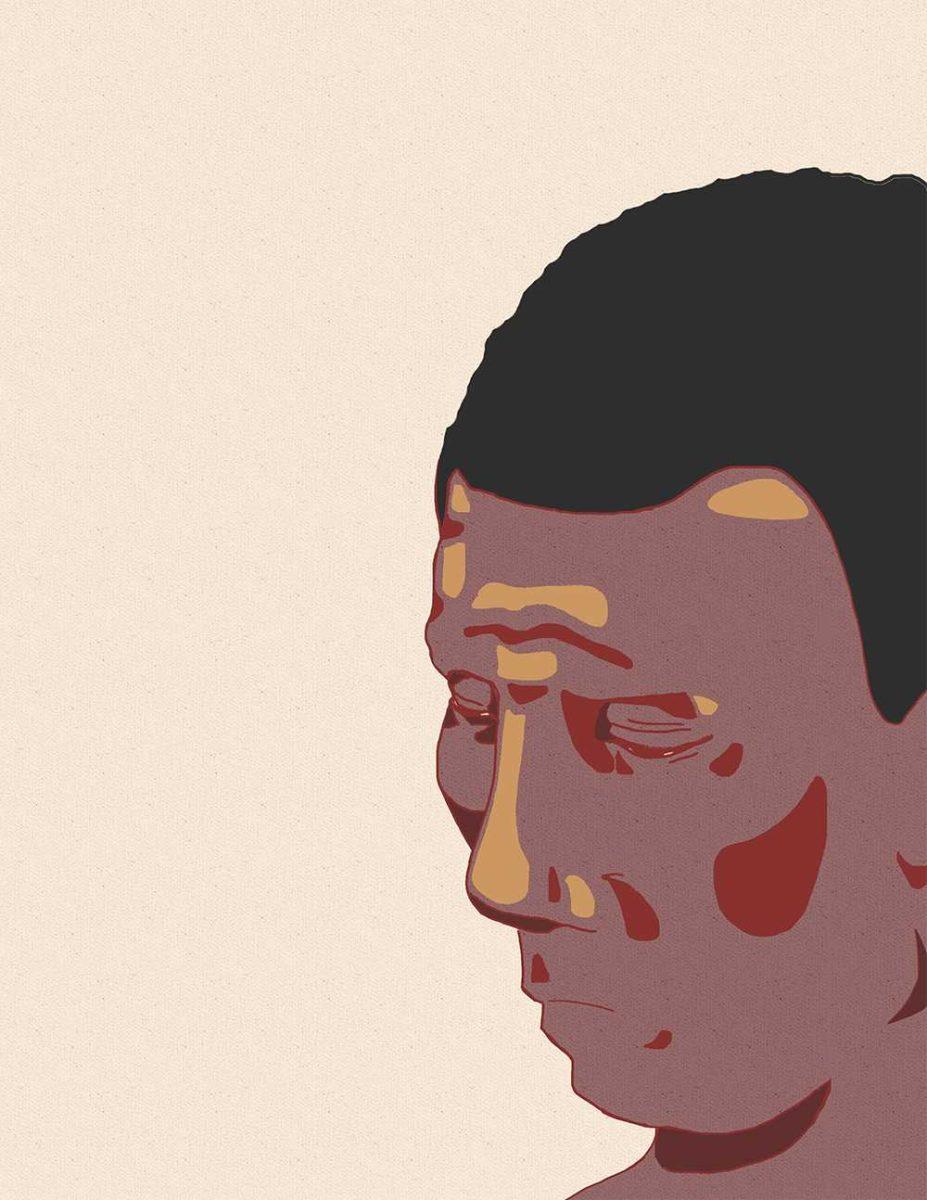

Millicent Foster found out she had AIDS in 2003.

She was diagnosed while she was living in Angie, La., after multiple visits to the emergency room for physical difficulties.

“When I found out, the most I knew about HIV or AIDS was, you can get it from being gay, or you got it from blood transfusions, or you could get it from using drug needles,” she remembered. “I never heard anything about getting it from unprotected sex.”

She first noticed her hands becoming numb, which made her job as a beautician difficult. She later grew worried as her hair fell out and her skin grew dark from the neck up. But it wasn’t until a year later, in 2002, that her symptoms began intensifying and a doctor finally suggested an HIV test.

Two weeks after the test, her results were positive. Her viral load (the measure of a virus in one’s body fluid) was high enough to prove she had an established case of AIDS.

“‘We estimate you might live about six months,’” Foster recalled the doctor saying. “‘We may not be able to bring it down, and we may not be able to do much for you.’”

But she beat that estimate, “Thanks to God.” Since her diagnosis, Foster defeated an addiction to crack cocaine, raised a granddaughter, buried her only daughter and continues to resist her bodily disease. And after seven years, she began speaking to community groups around southern Louisiana about her experiences in an effort to help prevent the further spread of HIV.

The Struggle of Prevention

Organizations like Baton Rouge AIDS Society make HIV information readily available, but the number of recorded AIDS cases in Baton Rouge continues to grow, making the city one of the highest AIDS per capita in the U.S. Despite offering treatments, testing and other preventative information, BRASS still struggles in its outreach to the community about the effects of contracted HIV and the necessity and responsibility of residents to prevent its growth. But people often aren’t aware of these provisions or that they even have HIV according to LSU Health Promotions Coordinator Sierra Fowler.

“They don’t have insurance, or they don’t know that they have these [AIDS Service] organizations or they just don’t even know they’re infected,” Fowler said. “You can have HIV for up to 10 years and not have any symptoms, and you think that you’re completely fine. Then you get sick and you’re already at full-blown AIDS status.”

Fowler said this lack of personal knowledge partially accounts for Baton Rouge’s growth in AIDS rates. While more people may have contracted the disease in recent years, more people who previously had HIV now have AIDS, or people have discovered their previously dormant illness. This, in turn, inflates the current rates.

Apathy also plays a part in this inflation. Some locals affected by HIV don’t want to know their status with the disease and don’t care if they spread it to others.

Foster has spoken to several church groups and community organizations about her own AIDS diagnosis and the importance of HIV awareness. And she’s come face to face with residents who know and care little about the issue.

“A lot of people know you can contract HIV from unprotected sex, but still a lot of them will not use condoms. You feel it can’t happen to you,” She said. “HIV does not discriminate. It don’t care how old you are, what color you are or what your sexual orientation is. It’s out there and it’s real, it’s very real.”

The Mission

Along with other readily available information and services, BRASS’s website explains the nature of the HIV virus and why AIDS is essentially incurable: HIV is a virus that attacks T-cells, or cells that fight disease and infection. AIDS is the final stage of an HIV infection when one has no T-cells to fight off other infections or diseases at all. With such weak immune systems, the infected are prone to die from other contracted illnesses. And while treatments exist to slow HIV if it is recognized before it develops into AIDS, none of these treatments cure the virus. They only slow it down.

Work like Foster’s plays an important part in engaging residents on a personal, visceral level to better promote a message that local organizations like BRASS continually address. With so many residents unaware of the full and far-reaching effects of HIV, local organizations dedicated to preventing the spread of this disease have a specific strategy: educating both the infected and those who think they’re unaffected. By informing the uninfected about how to prevent and avoid infection, and making sure residents with the virus are aware of their cases and won’t spread the virus further, residents can collectively stop the spread of disease and dedicate more time to helping those who have HIV or AIDS.

Gonzales’ Face to Face Enrichment Center founder Gabrielle Johnson began working with AIDS patients and outreach with BRASS in 1998, but created the Enrichment Center to address AIDS and other community issues in Ascension parish. She regularly speaks to schools, churches and community centers about HIV statistics and prevention methods, and both organizations’ offices offer free HIV testing that she said has become increasingly straightforward. The needle-to-vein blood sampling is no longer necessary.

“We don’t mess with needles here,” she said, referring to the potentially un- attractive blood sampling test method.

The Enrichment Center’s small but invitingly cozy office hosts counseling space and pamphlets on HIV and other health information along with the free OraQuick ADVANCE® Rapid HIV-1/2 Antibody Tests. These tests mix an oral swab from one’s mouth in a bottle of solutions that show HIV results in a matter of 20 minutes.

“I wish more people would come and get tested,” Johnson said. “I mean, it’s here and it’s free.”

Johnson said her organization outreach always seems well received. Most churches and schools she visits often ask for her organization to return.

Face to Face presentations seem particularly impactful to schools, she said.

“The kids are amazed. Whenever we talk about the stats and the symptoms of HIV it’s like their eyes get really big,” Johnson said. “We think we’re having a positive effect on them, and we hope we are, but we’re still getting those positive test results.”

Despite positive feedback from using this information in her outreach, Johnson said some attitudes undermine her organization’s work. She explained certain victims aren’t concerned about the severity of these diseases; they neglect tests out of fear of positive results or they actively seek out diseases for governmental benefits.

“There are those people who they call ‘bug chasers’ who want to get infected so they can get the benefits like the housing,” Johnson said. “So they’re intentionally trying to get infected.”

Under the Louisiana Ryan White Health Insurance Program, those affected by HIV can receive health insurance aid and temporary or potentially permanent housing.

Johnson also added that most cases who test positive for HIV in the Baton Rouge region are high school men, many of whom aren’t concerned about the consequences. She explained victims can feel complacent in contracting these diseases because they come from poor living environments, have bad role models and feel they will never amount to anything greater.

“Whether you’re HIV positive or negative, or your partner is HIV positive or negative, they have a choice as to whether or not they want to be with you,” Foster said. “Going around and being intimate with someone and not letting them know — that’s not a good thing.”

Prevention Money

Johnson’s husband, founder and CEO of BRASS, Reverend A.J. Johnson said the limited number of AIDS service

organizations also makes disseminating their information difficult and less impactful on communities. And with governmental funding continuing to dwindle, budget cuts largely limit these organizations’ resources according to Mrs. Johnson, while at least three other AIDS service organizations shut down as a result of cuts, she said.

“A lot of organizations have been cut down because of budget cuts, so there’s really not as many organizations out there doing the outreach as there once was,” she said. “That makes our job even harder because we have to take the slack from the other organizations who are no longer in the community.”

Louisiana disperses funds from the Ryan White Health Insurance program to various AIDS service organizations in Louisiana like HAART, the HIV AIDS Alliance for Region Two, the region that contains Baton Rouge and Ascension Parish. However, with recent cuts in this program, less money is dispersed through these organiza- tions. Mrs. Johnson also said the state’s Office of Public Health has made staff cuts in its own STI/HIV prevention program.

“We’re not doing enough because we have less money or no money in some areas,” Mr. Johnson said. “The state currently funds one organization to provide HIV testing to the entire region . . . being No. 1 [AIDS rates] this is not the time to reduce testing sites, this is the time to increase testing sites.”

Opening Up

To boost community outreach in the midst of these cuts the Johnsons approach residents on a personal and emotional level with work like Foster’s and outreach with churches.

Before Foster began speaking on the local issue, the first people she influenced were within her family circle. After her diagnosis, family and friends immediately sent her all the information they could learn and find about HIV and AIDS in hopes of helping her.

“I’m getting five or six envelopes a week full of information,” she recalled of the weeks following her diagnosis.

But Foster still had not fathomed talking to others about the disease and its effects on the community.

“I was still caught up with the stigma, I didn’t want anybody to know,” she said. “I had so many bad experiences in those seven years. I wasn’t comfortable with myself or talking about them with anybody else.”

She first whimsically spoke about her experiences at a family services open house at the request of her case manager. After being impressed by her testimony, one attendee put Foster in contact with A.J. Johnson, who helped her fortify her story-telling and helped her gain confidence in her abilities to retell her experiences to ultimately reach out to others.

“I heard you speak, and you have an awesome testimony,” she recalled the BRASS member telling her. “And people need to hear what you have to say, you could actually help somebody.”

Foster was skeptical, but she spoke at another open house for the organization, after which she started working with Mr. Johnson and speaking at different community events. By her first AIDS Day speech in 2009, she had eight bookings to speak about her experiences. She now works largely with Phenomenal Women with Voices, a travelling group skit that tries to encourage those affected by HIV. The group also works in other community outreach handing out information and protection for safe sex.

It was the responses following her speeches that Foster said gave her the confidence to continue speaking on her past. People still approach her in public to thank her for her story’s influence on their lives.

“I think if more of us were stepping out, the stigma wouldn’t be as bad,” she said. “More people would come out and get tested.”

Not Immune

September 22, 2013

Since being diagnosed with AIDS, Millicent Foster has become a promoter of AIDS awareness. She shares her story with others in hopes of helping those who are uneducated or unaware of the disease.