I’m sick and damn tired of hearing about the debt ceiling. And, like most people, when I’m tired of hearing about something, I shut my ears and start talking about it.

The debt ceiling, which is essentially the amount of money our government can owe at any given time, has risen more times than Gen. David Petraeus’s little soldier during meetings with his mistress-biographer.

For those of you not counting, the debt ceiling has risen 35 times since President Ronald Reagan took office in January 1981.

The last time the debt ceiling (not to be confused with another recently covered, ominous-sounding financial crisis, the fiscal cliff) qualified as “worth noting” to the general public was in 2011. Before 2011, the United States’ debt ceiling was set at a paltry $14.3 trillion, and like a meth-addled Denham Springs eighth grader, the country needed more money.

After a long-fought, bitter and truly pointless party-line battle, Congress increased the debt ceiling to $16.4 trillion in August of that year.

Surely our esteemed president and members of Congress have realized the negative effects of all this spending and the importance of staying within its means, right?

Nah, of course not.

The U.S. government will be at the end of its rope again in March, at which point it will either have to raise the debt ceiling again or shut down.

As much as I’d like to say we shouldn’t raise the debt ceiling again, we certainly need to.

A government shutdown would have catastrophic effects. For example, short-term interest rates would most likely increase, and the countries from which we borrow would lose faith in our ability to repay debts, making it more expensive to borrow in the future — I don’t know how they still have faith in us.

What the country needs is a policy solution attached to the inevitable bill that will increase the debt limit. The most likely answer is a dollar-for-dollar deal, which would force spending cuts to equal whatever amount to which the debt limit is raised.

The bill passed Jan. 1 to “avert” the “fiscal cliff” raises taxes on the rich and will bring in about $600 billion in new revenue over the next decade.

This isn’t even close to good enough. For perspective, the U.S. has been averaging a more than $1 trillion deficit each year since 2008. How does that make the $60 billion of revenue per year look now?

The country needs to make a political 180-degree turn that’s more severe than Taylor Swift’s genre reversal.

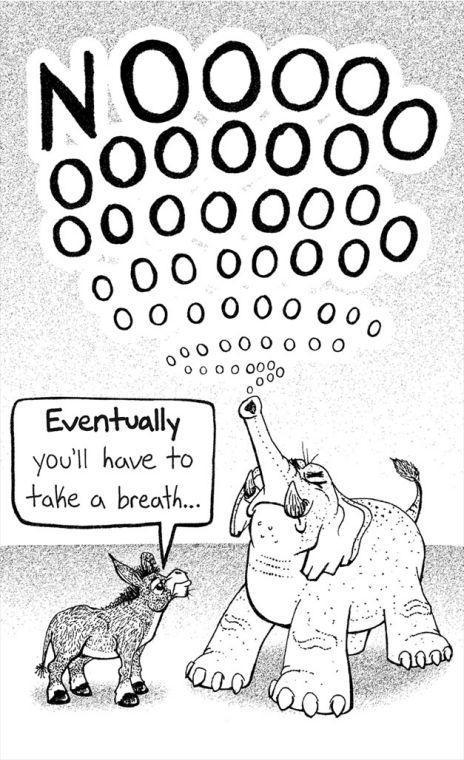

Gridlock in Washington is one of the U.S.’s more predictable aspects, and there will need to be some type of major shift if anything is to get done. Republicans budged a little on taxes during the fiscal cliff deal, so now the Democrats need to budge on spending cuts.

The only way to get the nation back on track is by closing the annual deficit gap, creating a surplus instead of a deficit and riding that surplus out of our national debt by 2060 or so — optimistically speaking. Only when we stop spending more than we take in can we stop increasing the national debt and, therefore, the debt ceiling.

The debt ceiling is not the problem. It’s one problem on a long list entitled “Fiscal Irresponsibility.” If citizens are not willing to force their elected officials to be responsible stewards of the taxpayers’ money, they may as well stop raising the debt ceiling.

Sooner or later, all those countries snickering about lending trillions to the best country in the world will try to cash in.

And we’ll have to pay — even if we don’t have the money.