Most colleges have a racing or solar car team, but only top engineering programs offer students the chance to build chemical cars.

This University is one of them.

The American Institute of Chemical Engineers at the University gives future chemical engineers the opportunity to put the skills they learn in the classroom to practical use.

Led by senior Aubyn Chavez, the University’s chemical car team offers some of the best training and the fiercest competition in the Southern region.

“We’re in the most competitive region, with Alabama and Florida, so it’s pretty tough,” Chavez said.

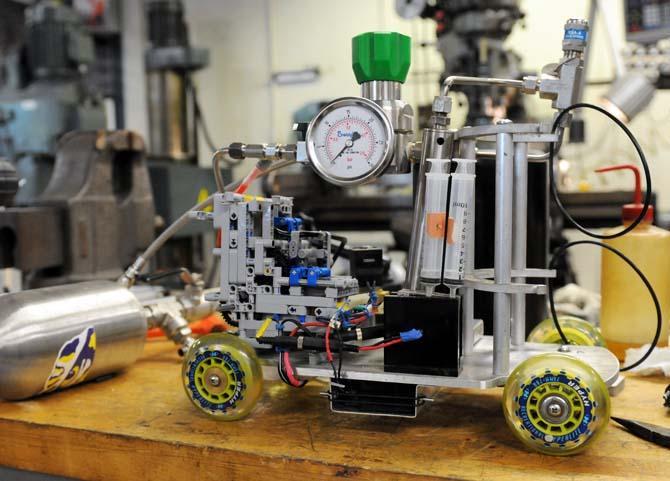

Chemical engineering junior Staci Duhon said the team is comprised of 12 devoted students who put countless hours into designing new car models, constructing new cars and creating the chemical reactions needed to fuel them.

“I feel like I spend my life devising doing these calculations,” Duhon said.

But what makes a chemical car so different from a regular machine?

For one thing, they’re fairly small. Chavez said constructing a large vehicle would break the rules of the contests in which they compete.

The car also does not utilize typical fuels like ethanol or solar power. Instead, it starts via hyper-fast hydrogen peroxide reaction and utilizes an iodine clock mechanism to stop.

Chavez said the completion of these chemical reactions serves as the basis for chemical car competitions.

Unlike most car-based contests, chemical car competitions are not races. They are modeled after over-under wagers integral to gambling games like poker.

“All the teams are given a distance, and whichever team’s car moves closest to that distance wins,” Chavez said.

But the University’s team doesn’t stake their reputation on guesswork. The group dedicates a substantial amount of its training to calculations that determine how far the car can travel when a particular amount of material is used for a chemical reaction.

When the group flew to Puerto Rico on March 20 to compete in the regional competition, they had no idea how far their car had to travel, as is the convention for these competitions. They had to make sure their chemical reactions performed as closely to the team’s predictions as they possibly could.

“We were in the machine shop day and night — we poured blood, sweat and tears into this,” Duhon said.

The top five cars of each region are invited to participate in a national competition. The University’s team achieved sixth place out of 15 cars at regionals, falling literally inches short of the leading cars but handily defeating its rival at Alabama. LSU’s car qualified as a wild-card pick for nationals.

This is a significant step up from last year’s competition, during which the team could not get its car to move.

Building this year’s car was no easy feat either. In Duhon’s words, anything that could have gone wrong did go wrong. The team members even had a part of their car confiscated before their flight back to Puerto Rico, despite following all of TSA’s guidelines.

Despite these setbacks, the team is proud of what they accomplished. Chavez said she feels as though she is much better prepared for a career in engineering than she was before she joined the team.

“I feel so much more capable of doing actual engineering things now that I’ve worked on this car,” Chavez said.

Duhon said that maintaining a competitive team and car requires a large commitment of both time and effort, but she considers any investments she makes in the car as an investment in her future.

“I feel so much more capable of doing actual engineering things now that I’ve worked on this car.”

Students build car fueled by chemical reactions

By Panya Kroun

April 6, 2014

Chemical engineering junior Staci Duhon (left) and senior Aubyn Chavez explain the car Monday, March 31, 2014 at the machine shop in the Chemical Engineering Building.