Let’s face it: Technology is outgrowing all of us.

The idea of social media, the Internet and even mobile phones seemed unachievable a few decades ago, and now technology has surpassed our wildest dreams.

So rather than spending an unlimited number of hours trying to figure out the mechanics behind iCloud, we focus on learning how to handle ourselves in this new online world.

We are taught to protect our social media accounts, reject friend requests or follows from people we don’t know and think before publishing any information we might regret later.

Above all else, we are taught to be honest.

Movies, public service announcements and reality shows center around exposing individuals who misrepresent themselves online, because — like us — the law is struggling to keep up with the ethics of these new means of communication.

But when government agencies like the Drug Enforcement Administration commit the same indiscretions a middle school child would make, it’s time to click the update button.

Facebook made headlines Monday after releasing a letter condemning the DEA for impersonating real people to communicate with suspects of drug-related crimes.

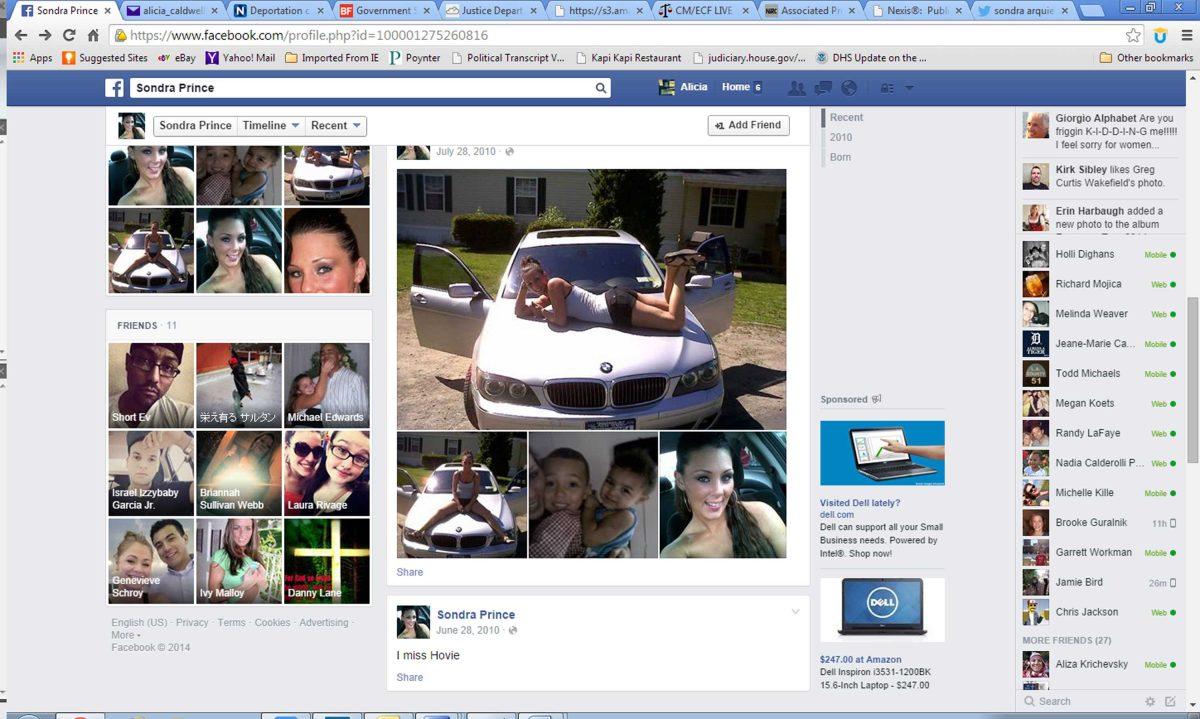

The letter was inspired by the case of Sondra Arquiett, who sued a DEA agent for setting up a fake Facebook account in her name.

Arquiett, then known as Sondra Prince, was arrested in 2010 and faced charges related to cocaine distribution. She pled guilty and was sentenced to probation.

While she was awaiting the trial, however, DEA agent Timothy Sinnigen created the fake profile, posted photos from Arquiett’s seized cell phone — one of which showed Arquiett in panties and a bra and another showing her with her son — sent and accepted friend requests from friends and suspects and held conversations with Arquiett’s acquaintances as well as a known fugitive.

All this happened without Arquiett’s consent.

The Justice Department obviously sided with Sinnigen, stating that while Arquiett did not give permission for the use of her photos on a fake Facebook profile, by allowing the police to access the information on her phone, she “implicitly [consented].”

But this argument is completely outrageous.

If Arquiett granted the DEA permission to search her house for evidence, they wouldn’t be allowed automatically to take her personal items and use them to communicate with other suspects in her name.

It’s an utter invasion of privacy and ultimately makes the DEA guilty of identity theft.

As part of the curriculum in my media law class, we have the opportunity to talk to middle school students about online safety. One of the first topics that comes up during these talks is the fact that, while misrepresenting yourself online and other inappropriate online behavior may be unethical, it is not yet illegal in the U.S.

Most of these kids will be exposed to blank profiles of strangers or spam Instagram profiles promising #likesforfollows, and we emphasize the importance of ignoring and reporting accounts they don’t know.

But if the Justice Department says it’s OK for government officials to misrepresent themselves online, what stops a child predator from putting a 13-year-old’s face as their profile picture?

Police and government agencies have solved crimes for hundreds of years without needing to steal private citizens’ identities, and simply because social media makes this process easier does not give them the right to do so now.

Cases like Arquiett’s might be the push our legislative and judicial branches need to begin reviewing and implementing laws to criminalize inappropriate online behavior.

The Internet and technology will continue to evolve at a rapid pace, but it’s time for the law to catch up.

Jose Bastidas is a 21-year-old mass communication senior from Caracas, Venezuela. You can reach him on Twitter @jabastidas.

Opinion: DEA impersonations call for regulation of online behavior

October 23, 2014

This image, obtained by the AP, shows the Facebook account created by DEA agents under the name of Sondra Prince, a drug crime suspect.

More to Discover