Some LSU students don’t know LSU has a rugby team. Some LSU students do, but don’t know much about the sport. “I know there was a movie Invictus, and that’s about it,” says chemical engineering junior Alex Thistlethwaite. As in the poem for which the film is named, the LSU Rugby team invokes the spirit of the author: retaining strength in the face of adversity.

History

Football garners the most attention at LSU, but for athletes who tackle combat sports differently, rugby offers a rugged alternative to an American classic. For American and international students alike, rugby delivers a fierce game that requires grit and bravado. Without padding, rugby players rely on thick skin to barrel through one of LSU’s most intense—and rewarding—club sports.

According to its website, the LSU Rugby Club has thrived on campus since its inception in the early 1970s. Rugby out-of-towners Rob Haswell and Jay McKenna were relying on flag football when McKenna shouted, “With you!” This signaled to Haswell, who played rugby in South Africa, that he was not the only player on the field. The two went to the LSU Athletics Department, who sent them in the direction of Hal Rose.

The three came together and rounded up enough ruggers to play on both sides. The team’s first match against Tulane ended in a 15-5 victory. Haswell’s emphasis on relentless offense and comradery is something the team values to this day..

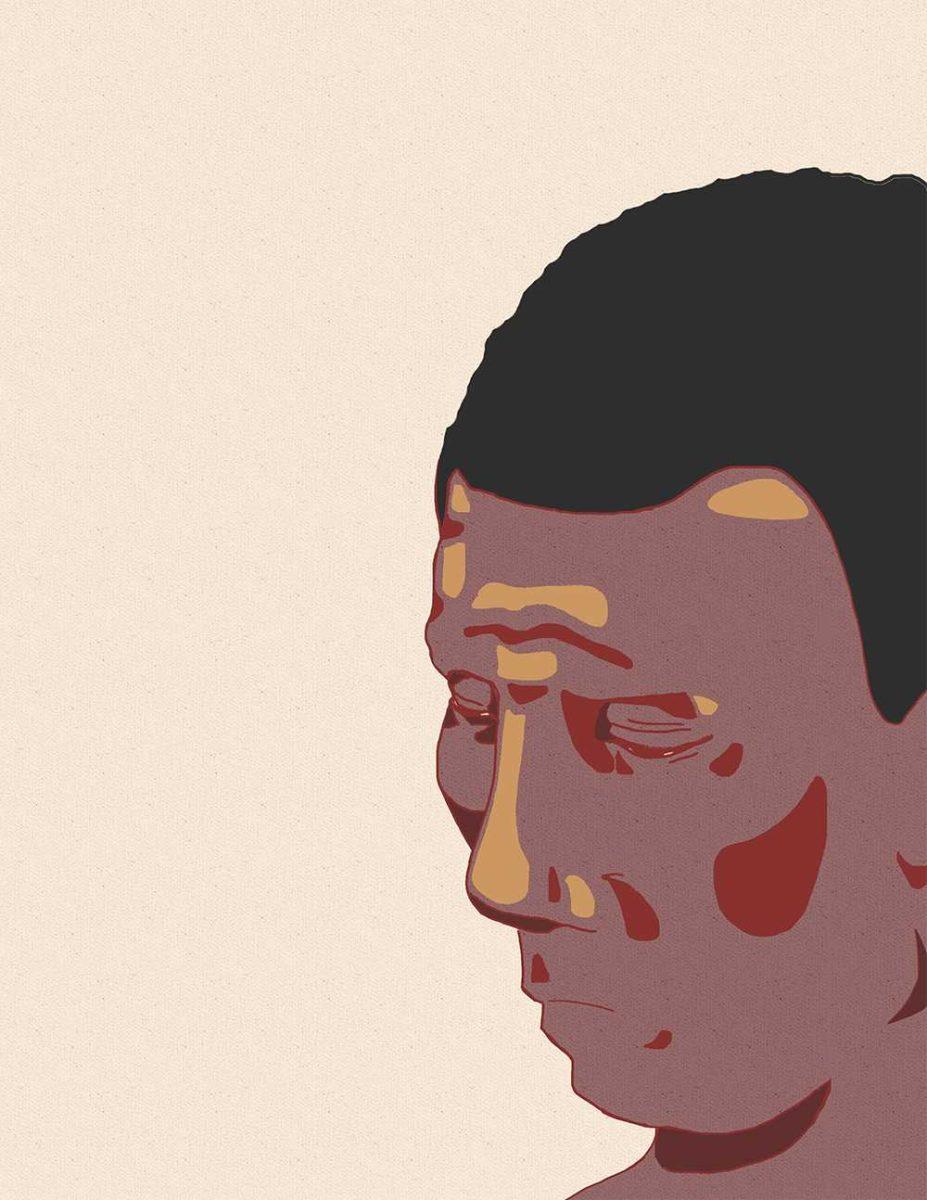

Former LSU rugby player Gift Egbelu agrees the team has been relatively successful, although it has “devolved in the last five years.” Baton Rouge has not implemented any youth or high school programs, which prevents young athletes from being exposed to the sport unless they travel to New Orleans.

“It’s trying to find itself, but without the ability to grow,” Egbelu said.

Despite difficulties in cultivating Louisiana youth for rugby, the Tiger Ruggers have posted winning seasons every year, earning top honors in the most competitive U.S. tournaments. The team has clinched championships in Louisiana, the Deep South and Texas divisions of the sport.

Traveling has become integral to playing this rare sport, with tours in England and the Bahamas and hosting teams from England, Wales and France among other countries.

Continentally, the team has hosted and been hosted at universities across the country.

Growing it here at home faces another challenge: how to maintain the traditions of rugby while adapting it for a modern audience. In the arena of sports, this means, as Egbelu says, “how to transition [rugby] to a profitable, institutionalized sport.”

Part of the struggle with institutionalization is retaining the amateurism while making rugby “family-friendly.” Rules restricting violence could, as Egbelu says some claim, “soften the sport.” It takes an understanding of the game’s mechanics to know how softening the blows on the field might compromise the game.

How it Works

Without any context, rugby doesn’t exactly translate to American audiences. As with most sports, the object of the game is to score as many points as possible. In rugby, this is done with successful “tries,” which means grounding the ball in the opposition’s in goal area, marked between two goal posts. Each try is awarded five points. A player can also score points by kicking the ball between the goal posts. In rugby, any player can score a try — which may explain the chaos seen on the field.

A drop kick gets the ball going, similar to the drop point guards experience in basketball. The ball must be bounced for this kick, but it is not bounced while the ball is in play. The ball must stay within the parameters of the field, and it must travel at least ten meters. Within these guidelines, rugby players are allowed to try nearly anything. There are no limitations once the ball is in possession—unless you’re tackled, that is. The opposing team may not tackle a player who does not possess the ball, but the ball-bearer gets the brunt of the defense.

The catch to rugby is that players cannot pass the ball forward. It can fly sideways or even backward, but “forward passes” are not allowed. Kicking is an option, but players normally kick to gain ground or avoid being tackled. Strategy-wise, kicking is not often used to advance the ball in place of passing or running, so players are advised to kick rarely.

The iconic images of rough rugby play are from the practices of rucking, mauling and the scrum. A ruck is when the ball is touching the ground, a scenario in which players come together to gain possession by pushing and stepping over the ball. If the ball is off the ground and players are attempting to gain possession, it’s a maul. Players must be bound together, pushing and grappling for the ball. A maul must be in constant motion or the game will be stopped.

A scrum is when the eight forward of each team lock down together, head to head, and grapple for the centered ball with their legs and feet. Hands are not allowed for this part of the game. These plays in rugby cause more physical contact and interlocking than any other sport. Because every member contributes equally, the team ethic must be strong for a team to succeed.

The physical ruggedness of rugby does not always communicate the importance of skill to those unfamiliar with the game.

“You can be an amazing athlete, but not at rugby,” says Egbelu. “How you think and see the field is crucial. It’s a reactive game, and you must play within the moment. Running fast doesn’t mean scoring.”

Strategy is also crucial because rugby cannot be played alone: the sport is devised to necessitate the involvement of various players.

“It’s not what you do for yourself, but your teammate,” Egbelu says. “It gives you no choice but to be team-oriented. Everyone has a job, and when everyone does it correctly, the team can win.”

For Love of the Sport

At risk of being considered cliche, Egbelu says that camaraderie is crucial to the sport.

“If you have ever played rugby, it’s an automatic fraternity,” he said. “You’re connected with people all over the world.”

Rugby not only transcends geographic barriers, but also age. Like golf, sailing and tennis, rugby is also a lifetime sport, with eighty-year-old men getting their heads in the game.

“It’s not about athleticism; it’s about skill,” Egbelu says, which challenges ideas that rugby is all brawn.

On the field, the battle is intense; the “rawest person you can be without judgment,” as Egbelu describes.

According to Egbelu, to release tension off the field, everything is solved with a beer.

“There will be fist fights on the field,” Egbelu says. “Off the field, you’ll buy that person a beer.”

The beer culture that is a part of rugby culture gives players a chance to celebrate victory and make friends out of former enemies– and perhaps numb some of that pain from sustained injuries.

Rugby is a sport for which 98 participants are not paid, according to Egbelu. Whether to utilize strategic skills, share glory with teammates or forge lifelong relationships, rugby is a game where reward outweighs risk.

Egbelu did not say why he first stepped onto the field several years ago, but he explained why he and others stay on the field: “For love of the sport.”