Biology professor Brent Christner and colleagues go deep into West Antarctic ice sheet for research.

Brent Christner and his colleagues aren’t going under the sea — they’re going under the ice.

Christner and his co-authors published a paper in Nature, a prominent scientific journal, documenting their discovery of microbial life in the waters 800 meters beneath the West Antarctic ice sheet.

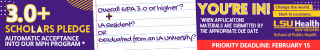

Christner and his colleagues are researchers with the Whillans Ice Stream Subglacial Access Research Drilling project, or WISSARD project, an ongoing multi-university collaboration funded by the National Science Foundation.

Graduate student and co-author of the paper Amanda Achberger said their research focuses on understanding what microorganisms are present in Lake Whillans and how those microorganisms are obtaining energy.

“We know there’s water beneath the ice sheet, and life needs water, but that’s not all it needs,” Christner said. “It needs a source of energy just like your car needs a source of energy to run.”

Achberger said this paper is just scratching the surface of what the WISSARD project can discover. Achberger said researchers in the University’s lab have identified the organisms in Lake Whillans but do not understand how those organisms function and what adaptations they have that allow them to live in an extreme environment.

Christner said researchers have speculated about the existence of life beneath the ice sheets for decades, but the traditional theory has been the coldest place on the planet cannot support life.

“If we were sitting here 20 years ago talking about life underneath the Antarctic ice sheet, you know, you’d get laughed out of the room,” Christner said.

One of WISSARD’s major obstacles was finding an appropriate drilling method. When samples were presented in 1999 as the first evidence of microbial life beneath the Antarctic ice sheets, studies citing the evidence were called into question because of the drilling methods employed in retrieving the samples.

“We’re talking about microbial life in a place that we’ve never been able to access,” Christner said. “The breakthrough in this project is literally the breakthrough in that we drilled through the ice sheet for the first time, specifically to look for life underneath the ice sheet.”

The team spent years planning the drilling and cleaning methods that would be used in the Antarctic to protect the environment and prevent contamination of the extracted samples. The equipment was tested in the U.S. as well as Antarctica multiple times before the team actually penetrated the ice sheet.

“The last thing you want to do is contaminate this environment that’s been hidden away for hundreds of thousands of years,” Achberger said.

Christner said the team will return to Antarctica in January to continue studying Lake Whillans and its microbiological ecosystem by drilling into an area of the ice sheet where researchers suspect the lake floods over into the ocean.

“Within the next two years, there’s going to be a number of articles that come out from our group and others that describe in more detail the biology of this system and the physiology of the organisms,” Christner said.

The WISSARD project’s findings have implications for the stability of ice in Antarctica that could affect even Baton Rouge, Christner said. Achberger said researchers are still trying to understand how the microbes interact with each other and with the oceans Lake Whillans feeds into.

“Now, that means that a bit of thinning or instability of that ice sheet means it could be floated, and what that would mean is that us, sitting here in Baton Rouge, we’d have beach front property because that ice sheet alone would raise sea levels about seven meters,” Christner said.

While Christner acknowledged this is an important implication of the study, he said as microbiologists, Baton Rouge-based researchers are primarily concerned with the presence of microbes beneath the ice.

“Part of it is understanding Earth … We don’t have a very good understanding of the microbial ecosystems that are here under our feet,” Achberger said.

The study also raises the questions of whether organisms that can survive in the harsh environment beneath the Antarctic ice sheets might also be able to survive in the harsh environments on other planets.

“I don’t know that Louisiana State University is going to be a center of polar research, but what I’d like to see us be is a university that is recognized for its microbiology-based research whether that be in Antarctica or that be in the high atmosphere or in coastal regions or deep in the Gulf,” Christner said.

Professor finds life in Antarctic ice sheets

September 2, 2014

LSU’s Dr. Brent Christner, who recently published a paper documenting a lake beneath Antarctic ice sheets, within the freezer room of the Life Science Building on Tuesday September 2, 2014.

LSU's Dr. Brent Christner, who recently published a paper on his discovery of a lake beneath Antarctic ice sheets, in his office in the Life Science Building Tuesday September 2, 2014.