When Leland Boyd woke up in the middle of the night as a child, he’d sometimes find his father Earcel in the bathroom, scrubbing his hands over and over.

“The next day you’d see him, his hands would be just red,” Leland said. “He would take a bar of soap and just scrub his arms for hours under hot water. He would be in the bathroom at least three times a month early in the morning for hours.”

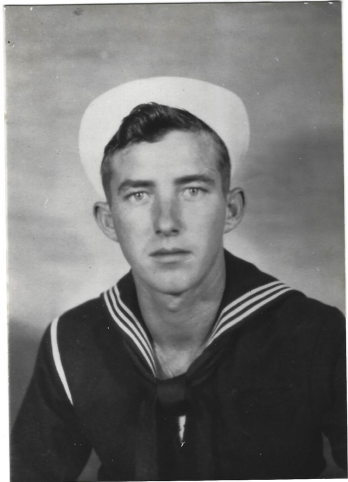

Earcel’ssons believed this compulsion was a result of nightmarish experiences during World War II, when Earcel participated in landing assaults on the Japanese in Guam.

During one raid, another son Sonny said, Earcel spotted a Japanese guard whose position put U.S. troop movements at risk. That night, Earcel silently crawled up a ditch, grabbed the guard from the back and slit his throat with a knife. He then had to lie in the ditch overnight with the guard’s blood encrusting his hands and arms.

“He never felt that he could get his hands washed clean,” Sonny said.

That happened when Earcel was 21, and later in the war, he shot an American soldier who attempted to reboard a landing craft after debarking on an assault. Earcel was trained to allow no one to reboard unless wounded or dead and shot the soldier, who recovered, Sonny said.

The Boyd brothers believe that their father’s rage and irrationality — which caused great emotional and physical distress for their family — was partly related to his experiences in World War II, especially the killing of the guard.

His propensity for violence also was apparent in his decision to join the Ku Klux Klan in 1962 when he was living in Concordia Parish, just across the Mississippi River from Natchez. And in the mid-1960s, he was one of the 20 or so members of the Silver Dollar Group, a violent Klan offshoot thought to be involved in several murders.

Earcel and fellow Silver Dollar members used their military experience to make homemade bombs and practice with them. Some were the types of bombs used in the attempted murder of George Metcalfe, an NAACP leader who had filed a desegregation lawsuit against the city of Natchez, and the murder of Wharlest Jackson, a Korean War veteran who took “a white man’s job” at the Armstrong Tire plant there.

Earcel was never charged with a crime, and no one was ever arrested for the killings. But FBI files indicated that the head of the Silver Dollar Group, Raleigh J. “Red” Glover, was a lead suspect in most of them.

And Sonny and Leland Boyd, both now in their 70s, said in recent interviews that their father’s involvement with the group upset them as teens and added to their growing disillusionment with him and his views.

Outlaw Country

While Sonny and Leland grew up on the edge of poverty, their father had an even tougher upbringing as one of 15 siblings in a rural part of central Louisiana.

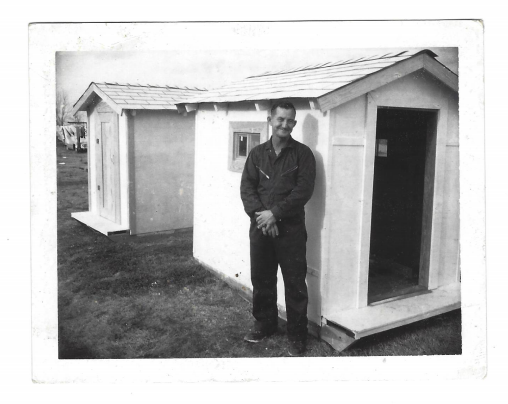

Earcel joined the Navy on his 19th birthday and saw action in the Marshall Islands, where he manned anti-aircraft and machine guns aboard a ship during Japanese attacks. His encounter with the Japanese guard in Guam occurred in 1944, when he manned an amphibious landing craft.

Sonny said he was later struck by how many Klansmen were World War II veterans and how they saw their efforts to keep the races separated as patriotic.

Earcel, like many white Southerners at the time, bought into the idea that Black people were content with their place in society and that NAACP leaders were stirring up trouble and threatening the Southern way of life, Sonny said.

Earcel was working at Armstrong Tire in Natchez in 1962 when he was recruited into the Original Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. In 1964, he joined the United Klans of America, the group responsible for killing four little girls in a bombing the year before at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

Sonny was a junior in high school at the time. “I went after my dad,” he said, demanding to know why Earcel would join a group that had done something like that. “I told him that if that’s the way the Klan was going to do things, then they needed to be brought down.”

Sonny accepted his father’s response that the bombing had happened in another state where he had no connections.

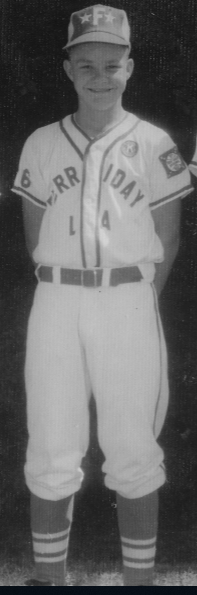

But after passage of the Civil Rights Act, racial tension and Klan activity became so bad in the Concordia Parish that John Doar, the assistant attorney general for civil rights at the U.S. Department of Justice, branded Ferriday, the parish’s largest town, “outlaw country” in 1965 and warned civil rights workers to get out.

Klan rallies and cross burnings

Still, Sonny drove his father, a Baptist preacher, to church on Sundays and to Klan rallies throughout his adolescence. He did not go into most of the rallies, opting to sit in the parking lot instead, which he says made some Klansmen angry.

“I only walked into three rallies,” Sonny said. “I thought they were stupid.”

Earcel brought Leland into more rallies since he was younger. Leland even recalls wrapping multiple crosses in burlap and soaking them in diesel for cross-burning rituals.

Sonny described a time when a burning cross fell over, almost catching a few Klansmen on fire at a rally.

“You can imagine all these Klansmen in their robes grabbing their skirts, you know down at the bottom, hustling off like a bunch of women in robes to get away from the fire,” Sonny said. “I always thought that was a funny moment.”

Made to Maim

Thanks to their dad, Sonny and Leland were no stranger to explosives. While living in Ferriday, Sonny helped hide two gallons of gunpowder in the family’s attic. Earcel stored grenades in their shed and occasionally in the back of his car.

Sonny said the Klansmen practiced with the bombs. “They’d take them down on the levee, and they had slow-burning fuses on them,” he said. “They would light them and throw them down the levee and roll down to the water.”

When Earcel met with other Silver Dollar members, including Glover, the group’s leader, at the café in the Shamrock Motel in Vidalia, Louisiana, Leland would eavesdrop on the men’s conversations from a booth over.

He recalls one time when Glover suggested the men bomb a church in Natchez. “That’s not gonna happen,” Leland says Earcel responded.

Glover, who was known as “Red” or RJ, was the prime suspect in multiple killings that went unsolved. He also frequented the Boyd’s home. Though he was friendly at times, he could go into a rage for no reason, Sonny said, adding that the family was terrified of him and his outbursts.

Glover also became familiar with explosives during World War II in the Navy, and FBI agents tagged him as a psychopath.

“Anybody at that time could go find a stick of dynamite and blow something up, and it was mostly for fear,” Leland said. “When RJ Glover builds something, it was made to maim.”

Leland and Sonny believe Glover, who died in 1984, was likely responsible for most of the major bombings in the area.

Losing respect for their father

Sonny said he lost more respect for his father as the bombings expanded.

Earcel Boyd had been friends with Frank Morris, who died after his shoe repair shop in Ferriday was burned in 1964, and he had angrily tried to find out which Klan members did it.

But by the time Wharlest Jackson, a Black man who had just received a promotion at Armstrong Tire, was killed in 1967, Sonny said, Earcel seemed indifferent.

Jackson was a Korean War veteran who had moved to Natchez with his wife in 1954. He loved to hunt and fish, play jacks with his four daughters on their front porch and wrestle with his sons.

He was involved in the NAACP and was friends with George Metcalfe, the local NAACP leader, who had survived a car bombing in 1965.

Jackson was promoted in early 1967 to chemical mixer at Armstrong Tire, a position he took despite warnings that taking such jobs would result in him or any other Black man being “taken care of” by the Klan.

After an overtime shift that Feb. 20, Jackson checked out of work around 8 p.m. He traveled two blocks in his green Chevrolet, then switched on his left turn signal. That ignited an explosive charge that had been placed under the truck’s cab below the driver’s seat.

The explosion shattered windows of nearby homes and killed Jackson immediately.

“Jackson remains a hero of mine, in a way, an unspoken hero,” said Sonny, who by then was out of high school and working in the area. “He was ‘just a black man trying to take a white man’s job,’ is the way it was looked at. But it was more than that. He was a patriot, trying to take his place in a society. He had kids that he wanted to have the same opportunity that all the white kids in the area did. And he was fighting for it.”

Sonny is sure his father was not involved in Jackson’s murder but says he did know something was going to happen. Glover and others at Armstrong Tire told Earcel to be away from the plant after work that day and in a place with people who could confirm he was not around the plant, Sonny said.

His father’s indifference toward the injustice set Sonny off “like a mini–bomb.”

“It kind of broke the faith between me and my dad at that time,” Sonny said. “I kind of lost my respect for him.”

Sonny, for the only time in the interviews, broke down in tears at the question of how long that anger lasted. “It’s still there,” he said. “I don’t think it will ever go away.”