For 70 years, Wyatt Houston Day – who, modestly, considers himself “top of the heap” for his craft – has been collecting books. Before the new year, he sold his beloved collection of African American poetry to Louisiana State University.

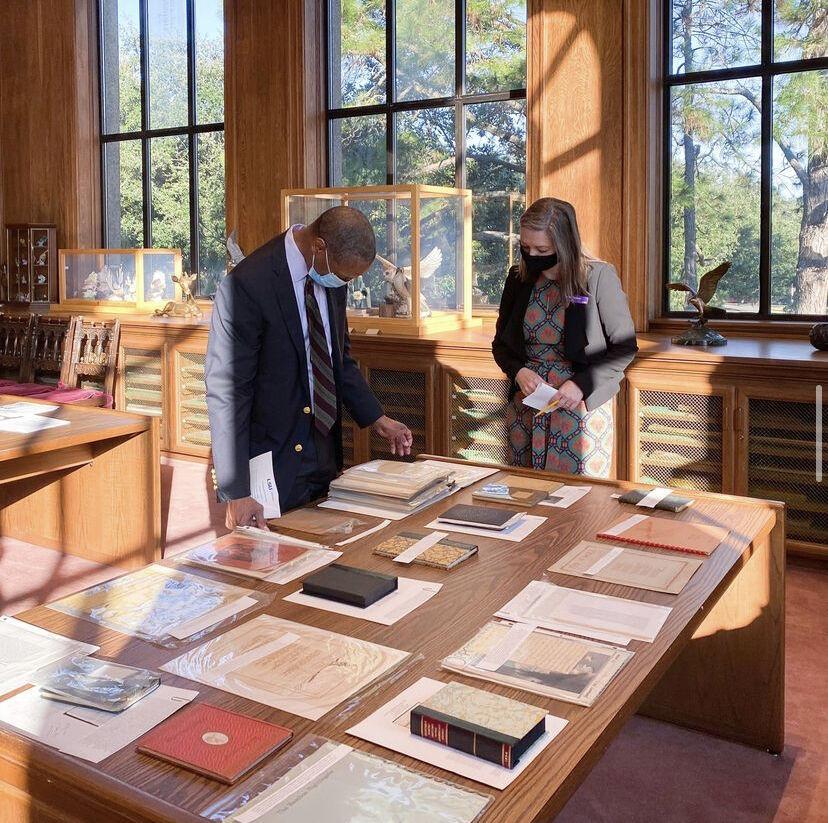

The Day collection, now available for public viewing at the Hill Memorial Library Special Collections, is one of the most important collections of African American poetry in the country, appraised at $612,940.

“Building this collection was like a challenge with a huge pot of gold at the end,” Day said. “I owed it to the collection to find it a good home.”

The breadth of the materials is extensive. Spanning the early 18th century, the Harlem Renaissance, post-Renaissance poetry and the 1960s and 1970s Black Arts movement, the collection features first editions and original manuscripts from hundreds of poets, including Gwendolyn Brooks, Langston Hughes and Sonia Sanchez.

John Miles, the curator of books at LSU Special Collections, said he initially reached out to Day searching for one particular book. But when one conversation led to another, and the two literature-enthusiasts formed a bond, Miles was surprised when Day offered him and LSU an entire collection.

Several other private buyers and institutions, including Duke University, showed interest in the collection, but Day “took a liking” toward Miles.

“John showed such interest and enthusiasm, and I knew the collection would be in good hands with him,” Day said.

LSU Library paid $380,000 for the collection, and Day gifted the rest.

Stanley Wilder, dean of LSU Libraries, said that the purchase was not a difficult decision. It is part of LSU Library’s effort to acquire collections that reflect under-represented communities.

“This was a special opportunity that presented itself,” Wilder said. “It’s given us a basis, and we can now continue building on this collection systematically.”

Day, now 81 years old, recalls collecting his first book when he was only nine. Raised on the lower east side of Manhattan, New York, he spent his younger years “book hunting” with his father at local book stores on and around 8th Street. He said the search is what he still loves the most about book collecting.

“A lot of the time, a great Black writer who worked in isolation often died in isolation,” Day said. “Those poets could have made some of the best work but had no one to read it. I wanted to read it.”

Day keeps his book collections in his home in the small, artistic town of Nyack, New York, where he and his wife moved to 27 years ago. When I asked Day why he decided to sell this remarkable collection, he said it was partially financial reasons, but more so to find them a good home as he got older.

The collection includes over 800 books by hundreds of authors, some prestigious and others more obscure. Narcissa Haskins, African American Studies librarian, was amazed, but not surprised by the diversity of poets that made up the collection.

“There was a lot of self-promotion during the Black Arts Movement; so there will be diversity and a lot of collaboration happening,” Haskins said. “It’s pretty typical to see diverse materials in collections such as this.”

Day confirms that this range was no fluke and is a reflection of African American poetry being inextricably linked to the experiences of Black people. Because of this, he said, the collection includes both highly sought-after materials and rare books with “no words on the spine.”

“Black poets were a part of what was going on politically and socially, not isolated in some special room in the house. Everything and everyone was connected.” Day said. “This collection is a voice of the community. It’s a lot of voices that came together as one voice.”

Miles hopes that current and prospective LSU poets and creative writers will find inspiration in these voices of the past. He emphasizes the importance of archival collections like this to narrate the experiences of enslaved people, specifically in their own voices.

Kalvin Marquis-Morris, dual communication studies and English senior, said that his favorite part of the collection was the original manuscript of the music cues for Langston Hughes’ 12-part poem, “Ask Your Mama,” inscribed by Hughes to poet Amiri Baraka.

Like Miles, he values this collection as more than just a symbolic win for diversity.

“This a crucial step toward the safety of Black students on campus and making them feel wanted, not just pulling them to the school for diversity numbers or to claim some DEI victory,” Marquis-Morris said. “The collection gives black students an opportunity to spark so much black innovation, genius, creativity and radicality.”

According to Marcela Reyes Ayalas, the LSU Library director of communications, LSU Library is entering the second phase of acquiring this new collection. Phase one was the initial announcement. Next, Ayalas wants to integrate the works into the curriculum and the community by hosting workshops, speaker series and group readings.

“We are planning to have a poetry reading event walk-through of the collection,” Haskins said. “It’s not going to be modern poetry slam or spoken word. It’s going to be a bit more traditional.”

Miles emphasizes his commitment to expanding this historical collection while embracing the contemporary poetry scene. Even though poetry is not what it was during the Harlem Renaissance, it still responds to similar political implications.

He also sees this collection as a prospective pull factor for potential LSU graduate students and professors.

“One thing I want, that I think is a possibility, is that this collection will attract students, particularly creative writing MFA students, but also professors,” Miles said. “This is us signaling a commitment to the university.”

Valuable African American Poetry collection finds new home in Hill Memorial Library Special Collections

March 27, 2022