Though 57 years have passed, Leland Boyd still can’t forget the smell of burnt human flesh.

In December 1964, Leland, then 12, stood in the doorway of a hospital room, where Frank Morris, a 51-year-old Black man from Ferriday, Louisiana, lay in critical condition after two men had torched his shoe shop.

Morris was a friend of the Boyd family. Leland and his father, Earcel Boyd Sr., had spent many afternoons after school in Morris’ shop. He repaired Leland and his siblings’ shoes and even ate dinner at the white family’s home on occasion, and the friendship had continued after Earcel joined the Ku Klux Klan in 1962.

“Frank, who did this?” Leland, now 70, recalls his father repeatedly asking Morris while he lay in the hospital bed. “I thought they were my friends,” Morris kept responding.

Morris died from his burns four days later in what the FBI viewed as a racially motivated arson-murder. Before his death, friends, family members and FBI agents would desperately probe Morris to identify his attackers, but he said he did not know them.

Leland is still haunted by that scene in the hospital room. “Human flesh smells different when it’s burned than beef, or pork or chicken,” he said. “It’s got an odor that you won’t ever forget. That’s all I could smell. It’s one of those experiences I wish I could get out of my mind.”

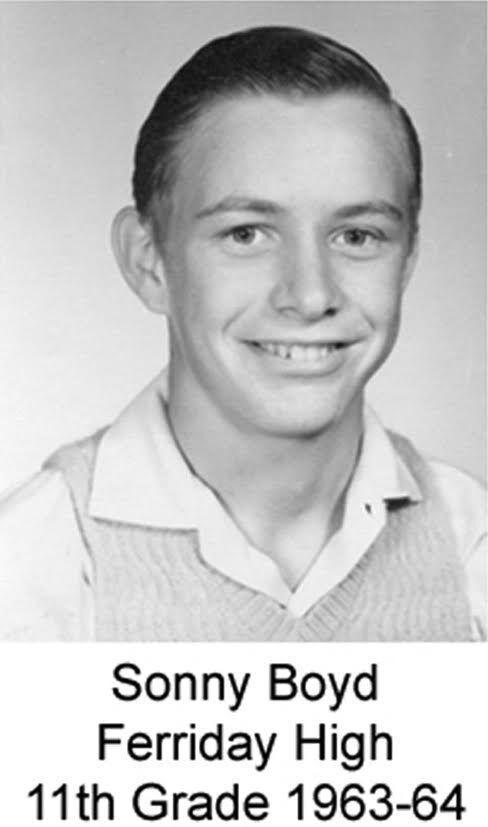

His brother Sonny, 74, said their dad’s anger over the gruesome murder also reflected more than just his affection for Morris.

Earcel was a member of the United Klans of America in Louisiana, a branch of the KKK, and he was infuriated, Sonny said, “that someone would come into his territory without his permission and do something like that.”

Earcel Boyd’s reaction to Morris’ death illustrates the conflicting impulses within him, his sons say, and how he gradually changed from a man who had taught his young children to treat everyone with respect, no matter their skin color, to an ardent segregationist.

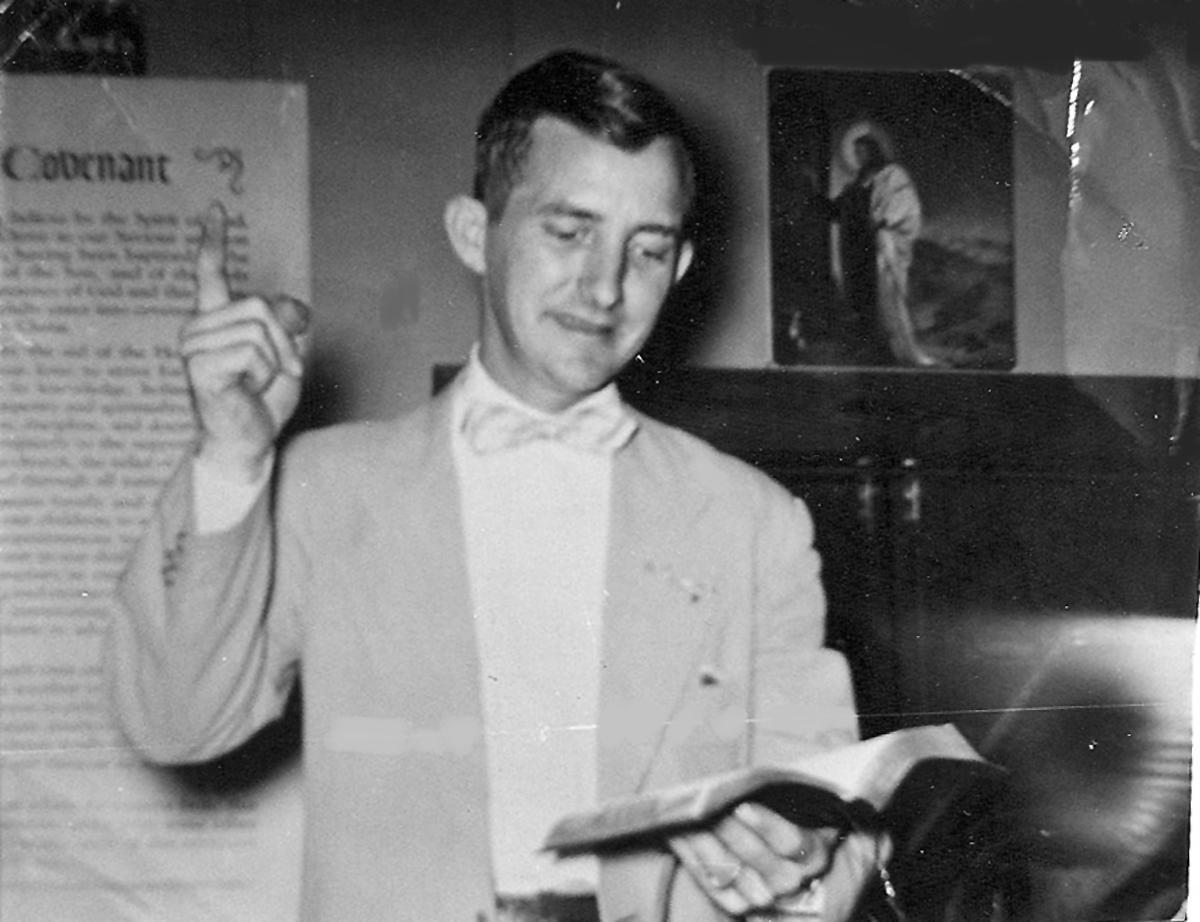

Earcel, an ordained Baptist minister, preached to Black congregations both before and after he became a Klansmen, sometimes attending Klan rallies on Saturdays and then preaching in Black churches on Sundays.

But he also “had a rage in him,” Sonny said, beating his children with his fists or any object he could find, especially as they began to question his beliefs and what the Klan stood for.

Earcel also belonged to the Silver Dollar Group, a violent offshoot of the Klan thought to be involved in several murders, though he was never charged with a crime or listed as a suspect by the FBI in any of the cases.

In multiple interviews, Sonny, who now lives in Oregon, and Leland, who lives in Natchitoches, Louisiana, offered a rare glimpse of what it was like to grow up in a Klan household. They also talked candidly about how that shaped their lives and who they are today.

Both say they sensed from an early age that their father was a hypocrite, given that he acted in ways that seemed so paradoxical. “Enigma” is the recurring word Sonny uses to describe him.

There are common elements between the Boyds and other Klan families whose lives were filled with hate and abuse.

Stanley Nelson, who was a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize for uncovering Klan murders during the civil rights–era in Louisiana and Mississippi, said children of Klansmen often grew up in unstable households.

“Most of the Klan children that I know and knew had enormous struggles during their lifetimes,” Nelson said. “In some cases, the fathers were domineering, cruel, were in total control–were not good providers oftentimes.”

“Race was no barrier”

Sonny said the seeds that would lead him to question his father’s racial views were laid when he was just four years old and the Boyd family was living near a 99-year-old Black woman who had spent her childhood as a slave.

Sonny recalled that he and his older sister, Lilly, would make their way down a dirt road pulling an empty red Flyer wagon to their Black neighbors’ house, about 300 yards behind theirs, in Fenwick, Mississippi.

Soon their wagon will be filled with free state commodities, like eggs, spam and milk, that the black family shared with the similarly poor Boyds. Sonny refers to the family there as Uncle Levi, Uncle Perry, Auntie Luella and Granny Cora, who told the children stories of her emancipation and surviving the Civil War.

“They treated us like their own kids,” Sonny said. “They were so good to us.”

Sonny said his parents trusted their neighbors and relied on their selflessness in sharing food.

“Never once did I ever think about their color when I walked into their house,” he said.

Living on the edge of poverty, the Boyds moved a total of nine times around Mississippi and Louisiana from the late 1940s through the late 1950s.

He said his father gambled away the family’s home and land in a poker game in 1949, forcing the family to live on a dirt floor in a Quonset hut at a chicken ranch owned by Earcel’s brother.

Around that time, Earcel began making decent money at the Armstrong Tire plant in Natchez, but much of it did not make it home or get to his creditors.

“Daddy didn’t like paying bills,” Sonny said.

Earcel also rediscovered religion. He had strayed away from it after fighting in the Pacific in World War II but later became a Baptist minister and began preaching in Black churches around Natchez, Mississippi.

The rest of the family, at the time three boys and their older sister, often accompanied their father to the services, where they were the only white faces in the crowd of swaying worshipers. Sonny said their family was well known in the Black community around Natchez and that Earcel at the time was teaching his children to respect everyone–white or black.

“Probably had you said anything to him about the Klans at that time, he probably would have slapped you,” Sonny said. “My dad, at that time, was teaching us that we should show respect and have respect for all people. And race was no barrier to it.”

“As a Christian, you can’t be that way”

But sometime in the 1950s, their father’s racial views began to shift. Like many white people around him, he became increasingly concerned about the growing civil rights movement.

Earcel at one point had told his sons that heaven would be a place of spirits without bodies or skin color. At other times, he said Blacks and whites would go to heaven, but that the eternal paradise would be segregated.

Earcel’s violent tendencies became clearer, Sonny said, and you could never tell how far he would take it or predict who would bear the brunt of his beatings.

Sonny recalled that the first time he witnessed violence from his father was when they lived near the Black family in Fenwick. Earcel picked up another brother, Shelby, who was then only 2, by one arm and beat him “with the sole of his shoe” for laughing during family prayer.

When Leland was nine, he questioned one of Earcel’s religious beliefs during a family car ride back from a church where their father had just given a sermon. Earcel often asked what his children thought of his sermons, but he did not tolerate questioning of any kind.

Leland didnot like the idea of “once saved, always saved,” a Protestant view that claims someone who turns to a life of Christ will continue doing good deeds and remain on the path to heaven.

When Leland voiced his opposition, Earcel pulled the emergency brake while driving down a gravel road, exited the vehicle and beat Leland on the side of the road with his belt, all in one sweeping motion that was over before the dust cloud behind the car could dissipate.

“He threw me back across my sister and said, ‘Boy, as long as you live in my house, you’re going to believe what I tell you to believe,’” Leland said. “And it was kind of a frightening experience for a 9-year-old.”

More violence at home

Armstrong Tire was a hotbed of Klan recruitment efforts, and Earcel was brought into the fold by a co-worker there in 1962.

As the Boyd brothers grew older, they questioned their father more and more, especially about the Klan.

“‘Dad, I understand enough to know that as a Christian, you can’t be that way,’” Leland recalls challenging Earcel for his involvement in the Klan. “I had a tough time coping with it. How could my dad encourage us to have the relationship with Auntie Luella, Uncle Levi and Granny Cora, and be friends with Frank?”

Leland, in his adolescence, was much stronger than his father, and at one point almost killed him.

After Leland and his younger brother suffered severe beatings one day, Leland pointed a loaded revolver at the back of Earcel’s head as he walked out of the room where he and his father had just been screaming at each other after the beatings.

“He was merciless that day,” Leland said. “I was just just ready to pull the trigger. And my mom stepped between me and him. And she said, ‘Leland, it’s not worth it.’”

One particularly violent outburst from Earcel directed at his daughter Lilly landed him in a mental hospital, where he received shock therapy.

“So he was away for five or six months, and during that time we didn’t really have an income,” Sonny said, adding that the episode “put us in such bad shape that we lost that house, too.”