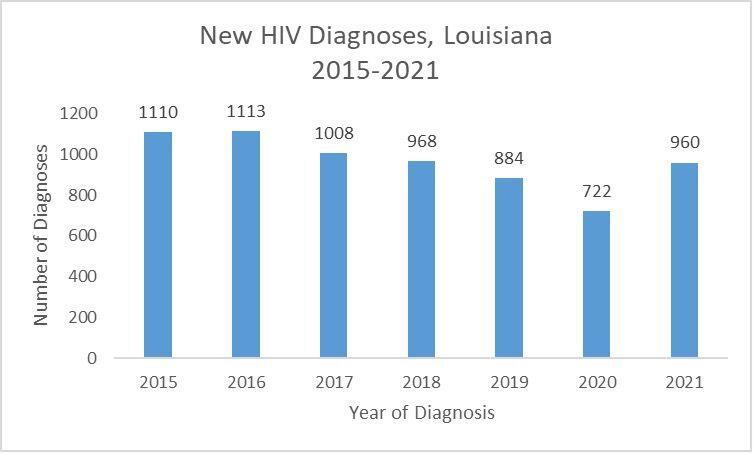

For decades, Louisiana was one of the worst states for HIV transmission, and in 2015, healthcare leaders created a plan to try to end the epidemic.

As they expanded access to prevention tools, health services pushed to ease the stigma surrounding the human immunodeficiency virus, new diagnoses dropped by more than 20%, and by 2019, Louisiana no longer ranked among the ten states with the highest transmission rates.

Then COVID hit, forcing the immunocompromised, like people suffering from HIV to isolate themselves. Many of the more than 22,000 Louisiana residents with HIV or AIDS lost in-person access to health providers, and newly diagnosed patients did not get the treatments that can keep them from transmitting the virus. Testing sites also administered far fewer tests, and five years of progress evaporated.

Preliminary data suggests that after a multi-year decline, new HIV diagnoses increased by about 33%, from 722 in 2020 to 960 in 2021, according to the Louisiana Department of Health.

“We don’t know exactly why that was the case,” Sam Burgess, the STD/HIV program director at the health department said. “We certainly know there was a lot less testing in 2020 and 2021. There were a lot of calls out to the public to avoid routine medical visits, so I think a lot of people delayed their screenings for sexual health. Some of the folks who probably would have been diagnosed in 2020 were diagnosed in 2021.”

Testing is picking up again with the recent lull in COVID cases, but the totals are not reaching pre-pandemic numbers.

Testing efforts at Crescent Care, one of the main HIV/AIDS treatment centers in New Orleans, were cut in half over the last two years. The clinic administered almost 8,000 HIV tests in 2019. Because lockdowns limited many patients to tele-health visits, the number decreased to 4,000 in both 2020 and 2021.

“The most effective means of HIV testing is getting out in the community and testing people,” Dr. Jason Halperin, an infectious disease specialist at Crescent Care, said. “In lockdowns and social distancing, all of that testing has stopped.”

“The second-best way to test is in clinics and emergency rooms,” he said. “Our clinics moved to tele-health, and our emergency rooms were focused on COVID.”

Crescent Care has not yet seen evidence of more HIV diagnoses among its patients, but it has had more syphilis and gonorrhea diagnoses over the last two years. An increase in other sexually transmitted infections can indicate an increase in HIV transmission.

Noel Twilbeck, the chief executive of Crescent Care, said the job now is getting people tested and back into care.

“We expect to lose a lot of ground in the work we’ve been able to do,” he said. “We’ve got to figure out how to step it up some. It might be three steps forward and two steps back, but we have to keep at it. We know this epidemic is not over.”

Other testing centers sometimes offer gift cards as incentives for getting tested but that has not been very successful.

“I can’t even bribe people to test,” said Sonya Milliman, the harm reduction and prevention coordinator at the Capitol Area Reentry Program, which tries to reduce health disparities in Baton Rouge. “People don’t want to be in that closed area. They want to be back home where they feel safer.”

Who faces the greatest risk?

Most of the HIV/AIDS patients in Louisiana live in the New Orleans, Baton Rouge, Shreveport and Lafayette regions. Of those, 68% are Black.

HIV, which can cause AIDS, began spreading among gay male populations in the early 1980s. But it also has become more prevalent among heterosexuals in lower-income areas with high rates of sexually transmitted infections. Drug users sharing needles also can spread it.

About 35% of people living with HIV in Louisiana were exposed to the virus through high-risk heterosexual contact, while 45% of the residents with HIV are gay or bisexual men, according to the health department.

Experts say that when people with HIV are on antiretroviral therapy, they have undetectable viral loads and are unable to transmit the virus. For people on treatment, life expectancy is similar to the general population.

Milliman, who was diagnosed with HIV in 2017, said she is tested at least once a year.

“I found out my diagnosis within six months of contracting the virus,” she said. “I started my treatment within two weeks of that diagnosis, and I was undetectable three weeks after that treatment began.”

Halperin said that after people test positive for HIV, doctors can start them on antiretroviral therapy the same day.

“If we have everyone with HIV on life-saving medication, that ends the HIV epidemic,” he said.

Burgess, the state health department official, said that “does not mean there will not be anyone living with HIV. It just means we should get to the point where there are little to zero new HIV diagnoses a year.”

Physical and personal effects

Gina Brown, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1994, said the hardest part of the pandemic has been the isolation from a community she relied on for support.

“I feel like a plant that’s not getting enough sunlight or water,” she said. “I sometimes feel like I’m wilting.”

Brown worries about people who have been diagnosed over the last two years.

“We learn how to take care of ourselves through other people who are already living with HIV,” she said. “Even if you don’t talk to anybody at the clinic, you hear conversations in the waiting room. People are talking about things like side effects from medication. You kind of file that away so that if you ever have that, you can try it. You also learn that there’s hope. There is life after diagnosis.”

Brandon Lee Brown, a New Orleanian in his late thirties who is living with HIV, contracted COVID-19 in September 2020. He was lethargic, dehydrated and had to force himself to eat. He lost 10 pounds during the two-week isolation period. Still, he says, he avoided hospitalization.

“When you’re immunocompromised, sometimes viruses hit you a lot different than when you’re not immunocompromised,” he said. “I felt that I was lucky that I didn’t have as much of a problem as other people.”

Easing the stigma

HIV and other sexually transmitted infections are socially stigmatized. People who contract them usually deal with judgment and rejection.

Brandon Brown said the stigma around HIV is not as bad as it was when he was diagnosed two decades ago but there is still progress to be made.

“We’re in the Bible Belt, a place where people don’t even talk about sex,” he said. “People don’t want to talk about sex or STIs, and it’s not a conversation that is had out in the open. Once we start having conversations, it will bring the stigma down even lower.”

Brandon Brown said his HIV status does not make him different from anyone else.

“We are still everyday regular people,” he said. “We have the same issues and same problems. Verizon, Amazon, everybody wants their money just the same, so we still gotta go to work. We just have this one little thing that we have to take a pill for.”

HIV prevention efforts are focused on sexual activity and drug use. But Gina Brown, who works for the Southern AIDS Coalition, a nonprofit group, said health officials should be looking at broader social determinants as well.

“We’re not looking at poverty,” she said. “We’re not looking at housing. We’re not talking about intimate partner violence. We’re not talking about the fact that Louisiana incarcerates more people per capita than any other state. We’re not talking about those things, yet we say we’re going to end this epidemic.”

“Young people are contracting HIV because we’re not having a comprehensive sexuality education conversation with them,” she added. “Nobody is out here just giving HIV. People are contracting HIV because we are not having conversations about prevention.”

“We’ve got to finish it”

Milliman, the health advocate in Baton Rouge, said educating young people on sex could work the same way as handing out sterile supplies.

Her organization has a safe syringe program that allows access to clean injection equipment and HIV, hepatitis C, and syphilis screenings.

“We’re not telling them to use,” she said, referring to drugs. “We’re just telling them, ‘If you’re going to, please do it in the safest way you can.’”

Education should go beyond just being safe, though. Milliman said life does not end with a positive HIV test.

“We have to educate on, ‘So, you tested positive. Let’s get you on treatment. Let’s show you that you can go on. You can still have sex. You can still have babies. You can still breastfeed your babies.’ That’s what we need,” she said.

Though HIV activists and healthcare experts have made tremendous progress over the last 40 years, there is still a lot of work to be done before ending the epidemic.

“It took many people screaming in the streets, and a lot of people dying to get what we have now,” Twilbeck said. “But we’ve got to finish it. There’s no reason another person should become infected with HIV. We have the data. We have the science. We have an arsenal of tools. We just gotta get it all together.”

Progress in lowering HIV infections in Louisiana during pandemic lowered, less access to treatments given

April 19, 2022

Sonya Milliman, a health advocate in Baton Rouge who has HIV, said her own virus levels were undetectable within three weeks after she began treatments.