Editor’s note: This article contains descriptions of sexual assault.

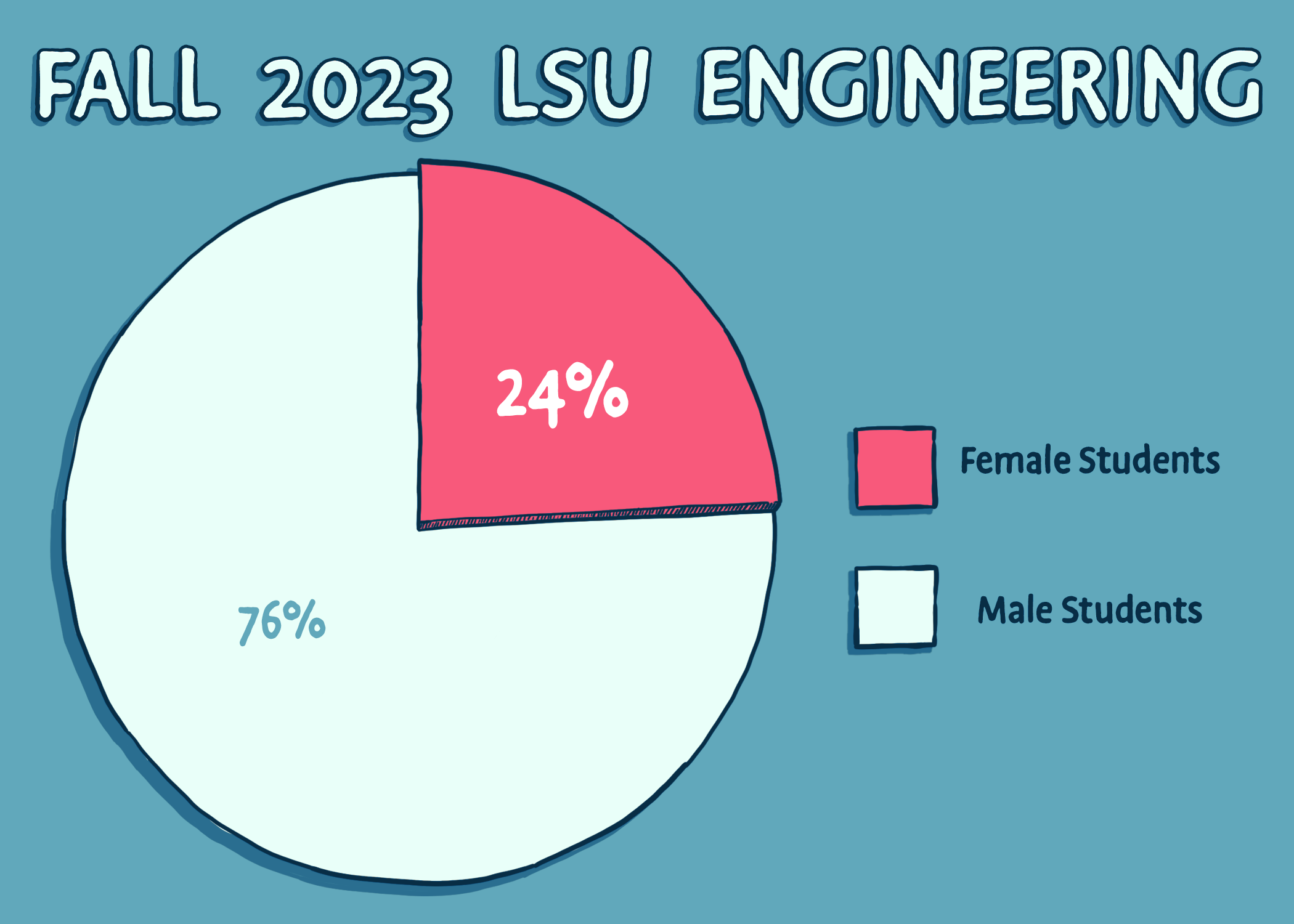

The LSU College of Engineering’s student body was 76% male and 24% female in the fall of 2023, according to the university’s website.

Organizations have increasingly spread awareness and advocacy in recent decades for more women to study science, technology, engineering and mathematics. The Reveille interviewed six women who have or are currently enrolled in LSU’s College of Engineering.

While six women aren’t reflective of every woman’s experience in engineering, their stories speak volumes on both victories and issues within the field. Among the six women, we found that:

-

Two of the six women reported experiencing potential gender-based discrimination in the field. Two women said they weren’t sure, and another two said they had not.

-

Of the two women who reported experiencing potential gender-based discrimination, one changed her major as a result, and the other changed her workplace.

-

Two of the six women in this story opted for anonymity, one for safety, and the other for job security.

-

Five of the six women are undergraduate students. One of the six is a doctoral candidate.

-

Three of the six women are women of color.

Here are their stories.

Minnie

Choosing anonymity for safety reasons, this student chose to be referred to as “Minnie” for this article.

Minnie visited her engineering professor’s office hours in the fall semester of 2022 because of her slipping grades. She walked through his office door in Patrick F. Taylor Hall on Oct. 11, 2022. The professor asked if he could close the door since it was the end of his office hours, and he didn’t want anybody else to come in.

“I didn’t know how to respond to it, so I was like, ‘Yeah, sure, I guess,’” Minnie said.

Expecting to sit across from him on the opposite side of his desk, Minnie noticed there was already a chair right next to him, on the same side of the desk. She sat down, not wanting to protest.

The professor noticed a symbol on the thigh of her sweatpants, and he traced his finger along the symbol, she said. Minnie said she was confused and uncomfortable with the interaction. She decided to dismiss the interaction and went back to his office a week later to discuss her exam grade, sitting in the same chair beside him.

“He was telling me that if I didn’t start doing better in his class, he was going to have to, like, spank me or something along those lines,” she said.

Minnie said after their meeting, he opened the door for her and spanked her bottom as she walked out. No students were in the hallway, she said, so nobody saw.

Already in a rush to go to work, Minnie said she didn’t fully process what happened until she arrived at her workplace. With encouragement from some friends, Minnie worked up the courage to submit an anonymous incident report to the LSU Title IX Office a couple of months later.

After several meetings with a case manager, she was told that the Title IX coordinator “can’t make a 100 percent decision on whether to investigate or dismiss without first reviewing the formal complaint,” according to an email that Minnie provided to the Reveille.

If Minnie decided to make a formal complaint, the professor would be notified, which was ultimately the reason why she only submitted an anonymous complaint. In another email, the case manager told Minnie that this professor had met with Title IX and the department chair the semester before to address concerns brought to their attention and “to discuss appropriate behaviors with students and to set expectations going forward.”

The case manager continued to say in the email that Minnie should reach out to the office if anything else happens so that the office can reevaluate the situation.

Feeling like the Title IX department couldn’t help her and that she couldn’t go to her own professor about falling grades, she eventually switched her major. Multiple factors went into her degree change, but her professor was a leading cause, she said.

The communications director of LSU College of Engineering, Joshua Duplechain, said that all faculty and staff must take annual training regarding power-based violence.

“Secondly, as employees of LSU, if a student reports such an incident to us, we are mandatory reporters to the Title IX office,” Duplechain said. “Those reports are then shared with the Office of Human Resource Management.”

Duplechain said the college also has one faculty member, called a confidential supporter, who has received additional training to support students and employees who experience sexual or power-based violence.

Dana

Requesting anonymity for job security, this graduate student chose to be referred to as “Dana” in this article.

Dana began working an assistantship with a professor during the spring of 2022. She felt misled when he allowed her to sign a contract agreeing to receive pay under the minimum requirement for an engineering doctoral candidates. She signed the semesterly contract to work 20 hours per week for $6,000.

Looking back, Dana remembers the professor said he was paying her the appropriate minimum for doctoral candidates, which made her feel like she was lied to. However, pay isn’t the only issue Dana ran into.

The professor scheduled weekly meetings with all of his other graduate student researchers, except for her, Dana said. The professor wasn’t her lead advisor, but she was working on research projects for him, meaning she should’ve had weekly meetings as well, she said.

The professor told Dana that she had communication issues, but she felt it was the other way around. When the professor needed to speak to Dana, he’d send her an email, summoning her to his office, she said, instead of scheduling a meeting ahead. She was expected to drop what she was doing and go see him, she said.

Other students told her that the professor would talk badly about her to other students during one-on-one meetings.

“If you need to know about my progress, ask me,” she said with frustration in her voice. “Nobody can talk about my work like me because I did the work.”

At a poster fair where students presented research, she said the professor treated only her unfairly by questioning her project more than the other projects. Since she was treated differently than the male graduate students, Dana believes the professor treated her this way because she is a woman.

“I didn’t expect at all to be treated this way here,” Dana said.

Every morning, she had to convince herself to get up and go to work, she said. The professor would threaten her job by saying he could replace her position with six undergraduate student researchers.

The professor, the department chair and the graduate adviser are all friends, Dana said, so she felt there was nowhere to go. After a year of work, Dana did not renew another semester contract and is now satisfied with her new job in another lab.

“For me, it was an easy out,” Dana said. “He was not happy. I wasn’t happy.”

Eva Counts

Formerly an environmental engineering major, bioengineering senior Eva Counts said it can be disheartening to see only five women out of the more than 50 students in an engineering class. Sometimes she feels anxious about making mistakes in group settings in class, worried that her mistakes will be blamed on her gender.

“Sometimes I can get a little self-conscious, but you just got to work through that,” Counts said.

Counts said she sometimes feels like her voice is drowned out due to the cliché of how engineering students often think highly of themselves. They hold themselves in higher regard, she said, so the cause of their self-consciousness may be something other than gender.

Counts believes her race is another important factor in her experience as an engineering student. She can only speak on her own experiences, she said.

“I’m a woman in STEM, but I’m also a white woman in STEM,” Counts said. “So I have a lot of privileges that definitely women of color don’t get to have.”

Eryn Kennedy

Chemical engineering senior Eryn Kennedy remembers excelling in math and science since she was in grade school. Her high school experience at LSU’s University Laboratory School continued the streak, where she had the opportunity to attend an engineering conference in London.

Having two older brothers in engineering careers, Kennedy believed it was a secure degree to pursue.

“I knew about all the great opportunities that LSU had to offer and how good the chemical engineering program was,” Kennedy said. “So it made it seem like a really great next step from high school.”

During her time at LSU, Kennedy studied abroad in Sweden and worked an engineering internship in San Francisco for a semester each. Now back in Baton Rouge, Kennedy spends most of her days in PFT labs performing research or completing class projects.

Upon reflection, Kennedy said she hasn’t had any of her core engineering classes taught by a female engineering professor.

“I do think as a female engineering student, it could be awesome to see more female professors at LSU,” Kennedy said.

A’ine Lusker

Engineering consumed the life of criminology senior A’ine Lusker before she got to college. At her all-girls high school in 2020, she was co-captain of her robotics team, and she took physics classes at an all-boys high school since they weren’t offered at her school. With her hefty experience, she was offered a part-time job in an LSU engineering lab as a high school senior.

Lusker met with her high school counselor and said she wanted to major in mechanical engineering at LSU. Yet, the high school counselor said Lusker’s ACT scores and GPA weren’t high enough.

“They said I should lower my standards,” Lusker said. “They said I won’t make it to LSU — I’m going to probably be a dropout.”

When Lusker returned to the counselor to show how her ACT score improved, the counselor accused Lusker of lying. Lusker said the experience planted self-doubt in her. So when she started LSU with an engineering major in 2020, she switched it a semester later due to the same feelings of self-doubt.

To this day, her biggest regret is changing her major from engineering, she said, and she still goes through her old physics notes just to feel the excitement of learning it. Lusker believes the counselor’s actions likely weren’t motivated by gender. Since she was one of the only nonwhite girls at her school, Lusker believes race could have played a factor but isn’t sure.

“STEM is my life,” Lusker said. “I don’t know what it means to me, but I know it just — it’s a part of me. Everything I do. I’m always figuring out how it works.”

Lusker’s love of engineering is so strong that she still finds ways to incorporate it into her life. Between 3D printing and watching mechanical engineering videos for fun, Lusker is also an officer of the 24-hour Lemons Club, an organization at LSU that teaches members about car mechanics.

Calliah Guillory

Chemical engineering senior Calliah Guillory grew up in Ville Platte, Louisiana, and graduated as the valedictorian of her high school.

Since attending LSU, Guillory has been part of several organizations, including the National Society of Black Engineers. She said she hasn’t experienced many issues with the college, and she’s thankful to LSU Engineering for awarding her many different opportunities, internships and research positions.

Graduating at the end of this semester, Guillory said she’s enjoyed getting to know all of her classmates. In the fall of 2023, there were 419 undergraduate students in the chemical engineering department, and 164 of those students were female, according to the department website.

“You pretty much know everyone, and that’s one of the things I like about chemical engineering is how small and intimate the classes are,” Guillory said.

Guillory was recently accepted to work full-time for Chevron, and she believes anything is possible. Being a woman in engineering is empowering, she said.

“It used to be a male dominant field, and women are on the rise,” Guillory said. “So it just feels great to see — more women are coming into position and doing great things.”

Contact the Reveille with news tips at [email protected], our online tip form or through our social media.