On April 3, community-based arts and music venue Yes We Cannibal announced it would be closing on April 21 to become a cutting edge, gestalt dining restaurant called Can-I-Ball.

This luxury dining service offered dinners at $50 per person for a 7-course meal for April 21, April 22, April 28 and April 29. On the 29th, the press conference after the meal revealed that this was all a staged artistic endeavor from Nigerian chef, artist and writer Tunde Wey.

Tunda Wey’s website reveals that he “uses Nigerian food to interrogate colonialism, capitalism and racism” and has “been featured in The New York Times, NPR, GQ, The Washington Post, VOGUE, Black Enterprise, Food and Wine.”

The Baton Rouge community responded quickly to the announcement of Yes We Cannibal closing with one Instagram comment reading “So where did y’all’s marbles go?”

Continuing with the deception, Yes We Cannibal made a post quoting The Economist’s “In Praise of Gentrification” from 2018, which received further backlash from those who felt Yes We Cannibal had forsaken its mission and forgotten those who it was built for. Comments on this post read “There’s no way this is real.” and “The phrase ‘avant garde speakeasy’ makes me want to put a power drill through my temple.”

However, this was all part of Wey’s master plan, which was to have a space where dining and art could be combined as a performative reenactment of gentrification that would act as a commentary on racism, capitalism, supply chains and alienated labor and the connections between those topics.

Despite opposition, the restaurant was a success. Yes We Cannibal revealed on its Instagram that Can-I-Ball “was a fully functioning prix fixe restaurant that operated for two weeks and served about 50 people.”

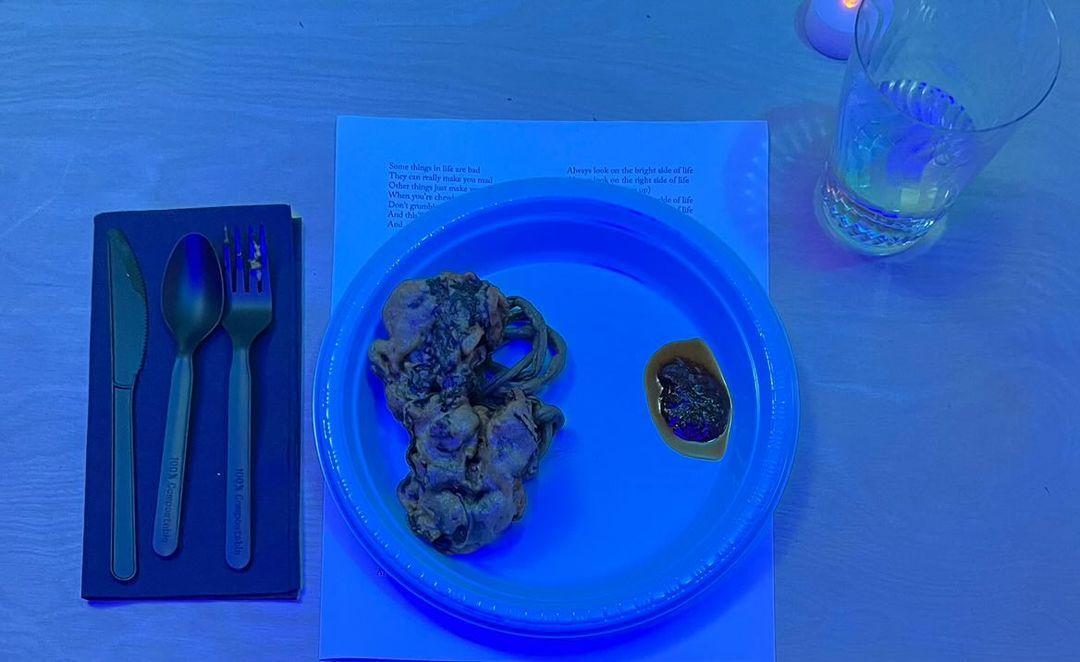

However, the dinner itself was much more complicated. On April 29, a group of guests arrived at Yes We Cannibal for the dinner with many dressed in stylish date night clothes. The guests were brought inside and told they were not allowed to sit at the tables for now and that they must sit on cushions on the floor for “mingling time.”

The walls were covered in balloons, which Wey later said were inspired by the story of his mother’s birth. He explained that the doctors couldn’t locate his mother’s head in his grandmother’s womb when she was pregnant, and this information quickly spread as news throughout their town that his grandmother had a “headless baby.”

“My grandmother, when my mother was born, said that my mother hid her head from heaven,” he said. “When I did this project in Pittsburgh, the balloons were sort of like in a cage with the balloons over the cage, and it was a reference to that.”

Soon, the guests were brought back outside then called in one by one to put on their “new skin.” Each guest was assisted by a server into a large solid color sumo-esque bodysuit with a mask over their face and gloves covering their hands.

This was meant to simulate life-support suits in a dark future where they are needed to survive and how that would change communication and dining.

“This dinner was rooted in this post-apocalyptic future where we are hiding ourselves from heaven and other things,” Wey said.

As the number of guests left outside dwindled down, two guests refused to be a part of it and decided to leave before they could be called inside to be put into the suits.

After being put into the suits, guests were placed at tables with people they didn’t know and told the rules of the dinner. No one was allowed to speak for themselves; instead, they must call a server over and whisper what they want to say into the server’s ear for the server to announce to others. Next, people could only lift up their mask to their nose to uncover their mouth when they are eating or drinking, otherwise, it must always be completely on. Lastly, no phone usage or pictures of any kind during the meal.

Then, the guests were subjected to a 7-course meal prepared by Wey. Each course was vegetarian and gluten-free. In between the courses, the guests were given prompts to answer through a speaker that echoed throughout the entire room.

Some of these prompts were “What is the most memorable dance you’ve had in your life?” or “What was one thing you wanted to be when you were a kid that you aren’t now?” Guests would then have to call their server over to announce their answer to the questions or comment on another guest’s answer to the question.

Then, the voice from the speaker commanded the guests to stand up and dance. After, the voice asked them to point to who danced the best, then the voice commanded for that person to sing his or her favorite song in front of the room. Finally, they wanted all guests to join in singing that person’s favorite song.

At another point, the guests were made to march around the room in a circle while the voice from the speaker sang. Then finally, all guests were made to sing “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” from “Monty Python.”

Wey explained that this art installation had a connection to death as well as social death. By placing people into uncomfortable situations where identity is blurred behind the suit, they are forced to rethink how they communicate. In 2022, Wey’s mother passed away.

“This is an exploration of death in a different sort of way,” he said.

“People have cried, people have had to leave due to various things affecting them,” the co-founder of Yes We Cannibal Matt Keel said. “I feel really reverent about that, I feel really honored about that to sort of see people have something in them budge in some kind of artistic space or experience. It’s really refreshing for me and encouraging.”

True to their usual anti-profit ideology, Yes We Cannibal didn’t make any profit during this restaurant installation.

“When we started working on this project, there was a lot of talk about supply chains, labor, gentrification, the way that dining plays into those things,” co-founder Liz Lessner said.

Yes We Cannibal paid for this endeavor through grants from the Arts Council of Baton Rouge, the Louisiana Office of Cultural Development, EBRPL, The New Orleans Center for the Gulf South, LSU School of Art and Visit Baton Rouge.

The $50 dollar ticket fees went straight to the servers who were paid $50 dollars an hour for their work, and each made about $1000 dollars.

“One of the things about Yes We Cannibal that Liz and I have always been interested in is that it’s really good that there is a lot of discussion about identity and social justice at this time,” Keel said. “It’s also a little stuck in places, so how do we experiment with talking about these same things but finding new languages, new conceits, new spaces where something new can happen.”