You may have seen the high-production Instagram videos with students clad in business attire and the dozens of reposts and comments. The social media buzz can only mean one thing: Student Government election season is here.

But this time is different, and you can already see it. Candidates announced their aspirations for executive office within hours of each other instead of rushing to be the first by weeks or months. The change is part of election reforms passed by SG in the fall to address what many felt was a broken system.

SG voted in September to cap campaign spending at $4,000, shorten the election season, expand voting time to two days instead of one and clearly establish the parameters around candidate disqualification, which had previously been up to the discretion of the judicial branch.

The next 50 days until voting opens will beg the question: Did the reforms level the playing field for students?

Colin Raby, a senator for the College of Engineering, said running for SG president in 2022 gave him a crash course in the flaws of the election system. He noted a laundry list of problems.

Some candidates got money from their family and could outspend their competitors many times over, he said. Some candidates would announce in November, months before the election. Some candidates piled on disinterested Senate candidates so they could spend more, as the old rules allowed. And some tickets had the coffers to spend “absurd amounts of money on food to essentially just bribe voters,” Raby said.

SG President Lizzie Shaw led the push for reforms, working over the summer to change the system that some had long felt favored wealthy students.

Campaign finance is perhaps the biggest change emerging from the reforms.

For the spring 2021 election, tickets could spend $2,000 per president-vice-president pair and an additional $100 for each candidate running on the ticket for senate or college council.

For the spring 2022 election, that $100 was reduced to $50. Still, the three tickets spent a combined total of almost $20,000, with one ticket alone spending almost half of that.

For both elections, donated items would go toward the spending limit but would only be counted as 60% of their value.

Campaign expenditures for these two elections, only a piece of the financial pie, totaled more than $33,000, according to an internal SG document circulating during the reform debates.

The rule allowing more money to be spent per each person on a ticket “heavily incentivized bringing people onto the ticket who could not care less about Student Government,” Raby said.

The 2023 election season will play by a different rulebook.

The spending cap for tickets is now $4,000. No money will be added for additional candidates running on a ticket. Donated items will count for 100% of their value. And only 25% of spending can go toward perishable items like food.

Campaign finance records have always been public, but they had to be requested. Now, they’ll be posted on the SG website under the election tab in early April, according to Chris Charles, the chair of the election commission.

Emma Long, a mass communication sophomore and senator representing the University Center for Advising and Counseling, thinks the spending cap will help prevent some of the bloat of disinterested candidates.

“I think that helps tickets find people that actually care about filling those roles, instead of just finding a warm body,” Long said.

When the reforms were debated in the fall, some senators disagreed on where the spending cap should fall. Raby said he favored $1,000 while others called for caps as high as $8,000. $4,000 was the decided compromise.

Some were concerned the cut spending would lower outreach and, consequently, voting tolls. But Raby noted that voting actually increased after the $50 drop in additional funding per ticket candidate between 2021 and 2022.

The spring 2021 election brought 5,207 student votes, around 17% of LSU’s student body. The spring 2022 election saw an increase of 38%, bringing the vote total over 7,000.

Long, who voted in favor of the reforms, thinks that election outreach should be the job of SG, not the candidates.

While the cap was higher than some proposed, the change still cuts campaign spending by thousands of dollars.

Another change brought by the reforms is a shortened election season.

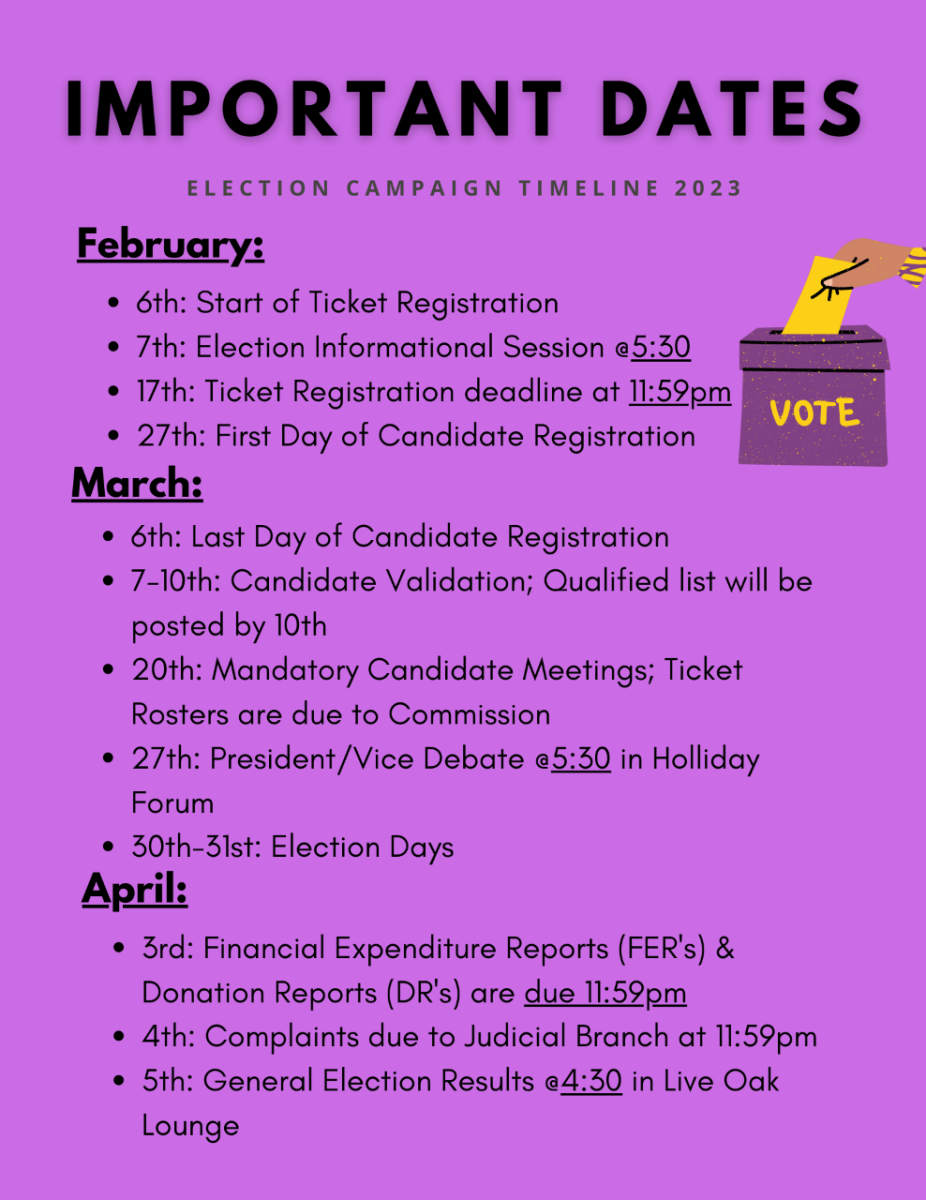

Students originally couldn’t announce their candidacy until Feb. 2, Charles said. Gone are the days of candidates announcing their run for the spring election in the fall and holding ticket meetings before winter break.

“It disincentivized the petty political strategy of trying to be first to win over as many people there that don’t know about the existence of the other tickets,” Raby said, pointing to the fact that, oftentimes, the first ticket to announce has been the winner.

Changes come for the student electorate too. Voting will now last two days instead of one. Raby said he hopes this will encourage more people to vote. SG elections have historically drawn relatively low student turnout, though the participation has ticked up in recent years.

Long looks forward to what the changes might mean for SG.

“The more I’ve been around Student Government, the more I’ve kind of not liked a lot of what happens in campaigns, mainly because it divides Student Government, and then you’re not able to really put in the work to actually get things done,” Long said. “There’s a lot of people that just kind of want to see their person win instead of pushing for better ideas and a better campus, which is what everyone says they’re going to do.”

Now, students are left to elect their first president and vice-president under the new rules alongside a fresh class of student senators and college council members.

How much the reforms succeed in opening the doors of SG to low-income students, encouraging voter participation and weeding out disinterested candidates may become clearer as the votes are tallied at the end of March.

Raby is hopeful the reforms will make a difference to future SG candidates and the electorate.

“It used to be that maybe you would have to fundraise $13,000 to have a chance at winning and you would have to announce a whole semester before, and all of these other things were really impractical for most candidates,” Raby said. “Now, with the limit of $4,000…and the restriction on announcing and planning the ticket, it makes it a lot more feasible for a lot more students to actually run for these positions and have a chance at winning.”