Most people reading this column didn’t vote in the Dec. 6 elections for Louisiana’s senatorial seat, statistically speaking. In fact, many won’t even vote for the next president in 2016. It’s a dereliction of our essential duty to democracy, which only furthers the masses of corrupt, ineffective politicians in government today.

Despite that, I don’t blame Americans for staying away from polling booths. It’s time consuming, politics is difficult to understand, and that creepy old lady standing behind you in line sounds more and more racist with every passing second.

Besides all the old people crowding up the place, polling stations reek of defeat and indifference. The number of times I was confident my vote made a difference equals the number of times I thought I could fly — a few, but ouch, I was wrong.

This feeling is reinforced everywhere you turn. Last week the Koch brothers announced their plans to spend nearly a billion dollars in the 2016 presidential election to make sure people vote the way they want them to.

It doesn’t just seem like your vote doesn’t matter in who wins — it actually doesn’t count.

A 2001 study examining every Congressional election since 1898 found only one election where it actually came down to a single vote: a 1910 election in Buffalo, New York. Statisticians compare the chances of a single vote deciding an election to winning the Powerball lottery.

Why does voting seem like such a pointless enterprise? Is it the lack of good candidates to motivate us? Is it the lack of a mandated voting holiday to

incentivize us?

While those things probably matter in the grand scheme, the biggest, most systemic reason voting doesn’t matter in the U.S. is its voting system. I’m not even talking about the electoral college, which is another matter completely.

The majority of the U.S. utilizes what is called First Past the Post voting, where everybody gets one vote and the winner of the election is the candidate with the most votes.

Sounds like a fair way to vote, right? Wrong!

FPTP is mathematically shown to devolve into a two-party system. The way the system counts ballots causes a great deal of the populace to vote for the candidate they hate the least, but who has the best chance of winning. Voting for a smaller candidate who more accurately represents your views only hurts the chances of somebody with some of those views making it to office.

FPTP voting is the reason third-party candidates see such little success, despite lots of interest. New-age Republicans are a prime example. Small government-liking, socially indifferent voters who may agree more with Libertarian Gary Johnson feel the need to vote for somebody like Senator Rand Paul because third-parties don’t win elections.

Louisiana’s jungle primary system is where the lower placing candidates are eliminated and a runoff between the top two decides the winner only marginally better. Despite this, Louisiana still produces middle of the road candidates like Bill Cassidy and Mary Landrieu, with grassroots favorites like Rob Maness falling to the wayside.

Just like with cars, beer and state-managed health insurance, the Germans have it better when it comes to voting. Introduced under the watch of major Allied powers after World War II, Germany uses what’s called Mixed-Member Proportional voting, which fixes the major voting issues present in FPTP.

MMP gives every eligible citizen two votes, with one going to a specific candidate and the other going to a political party who places their best candidates in the legislature based on how many votes they get.

It’s very easy to imagine how something like this would work out. Lets say I’m a vegan, socialist tree-hugger who wants to see more environmental issues in Congress. However, at the risk of sending a Republican to office, I feel the need to support the Democratic candidate. When the election rolls around, I can vote for both the Democrat with the best chance of winning and the Green Party.

None of this will change the fundamental problems present in the political system unless more people turn out to the polls to demand change. If we can’t bother to do that, then I hope you enjoy politicians that don’t care about you.

James Richards is a 20-year-old mass communication sophomore from New Orleans. You can follow him on Twitter

@JayEllRichy.

Opinion: It’s time for America’s voting system to change

February 5, 2015

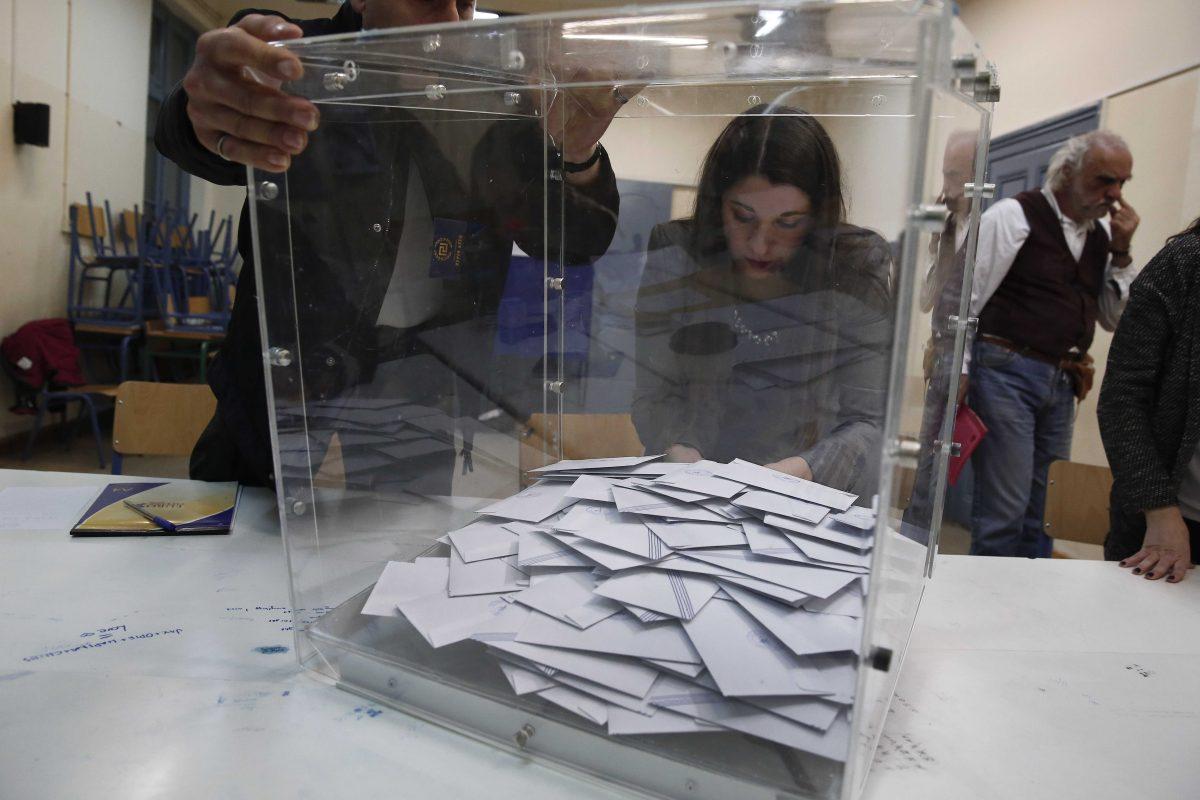

Election officials empty a ballot box to count votes at a polling station, in Athens, on Sunday, Jan. 25, 2015. A Greek state TV exit poll was projecting that anti-bailout party Syriza had won Sunday’s parliamentary elections _ in a historic first for a radical left wing party in Greece. But it was unclear whether Syriza had won a decisive enough victory over Prime Minister Antonis Samaras’ incumbent conservatives to govern alone. For that, they need a minimum 151 of parliament’s 300 seats. (AP Photo/Petros Giannakouris)

More to Discover