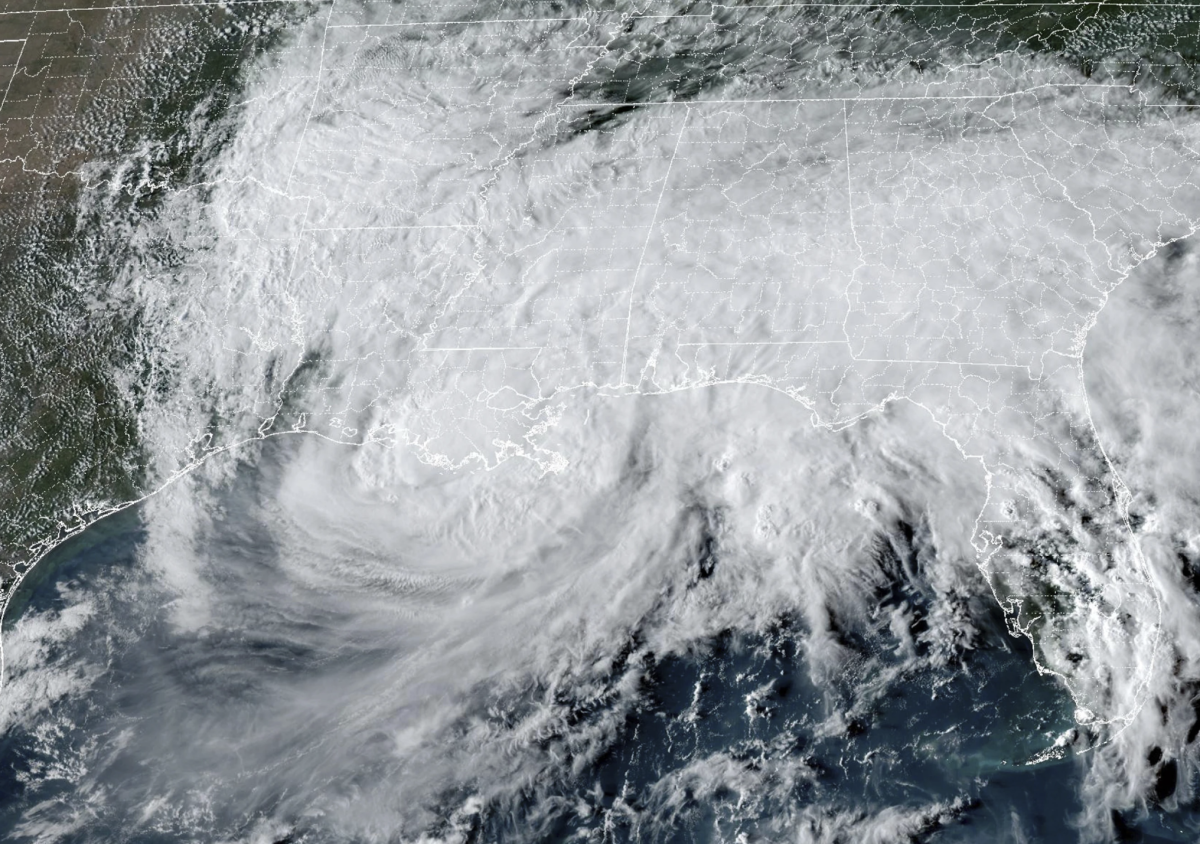

In May 2010, Coastal Fisheries Institute assistant professor Malinda Sutor led a crew-boat fitted with research equipment about 40 miles offshore to the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig, which exploded in April, leaving 11 dead and millions of gallons of oil gushing into the Gulf of Mexico.

Sutor and her crew measured oil droplets after dispersant was released, helping determine how to best contain the spill’s fallout.

Accompanied by more than 20 other large ships, Sutor’s boat would occasionally be directed hundreds of yards away, so the Coast Guard could light the ocean’s surface on fire, creating tornadoes of smoke on the water.

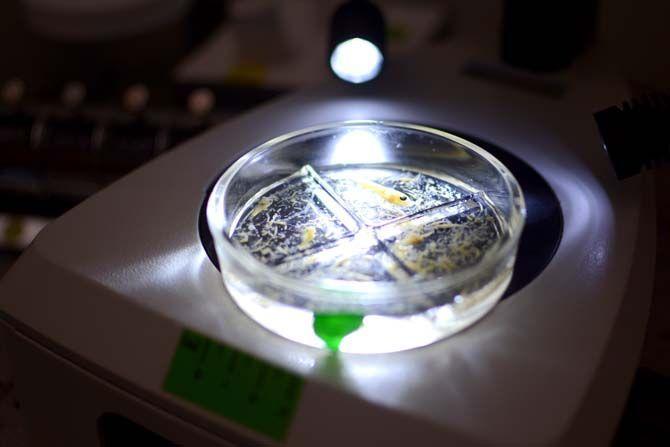

When Sutor’s team members were not gathering oil samples, they netted plankton, placing them in liquid preservative and hauling them back to the facility at LSU she nicknamed “LSU Plankton Lab” in 2008.

Her lasting impact on Gulf research has centered around plankton — a vital player in ocean ecology, Sutor said. Her team has collected thousands of samples, bringing them back to the laboratory at LSU for analysis.

“Even though they’re small, they’re a really important part in the basic ecology and function of the ocean,”

Sutor said. “That’s definitely been the focus of our research,”

In the months following the Deepwater Horizon spill, Sutor aimed to create a comprehensive picture of plankton and the oil spill’s effect on them.

Some members of Sutor’s team, many of whom were recent graduates, spent three months at sea, coming back to shore intermittently to drop off samples.

The team would split into night and day watches, with each group staying up for 12 hours to pack as much work into the day as possible. She said 24 hours on a typical research expedition, called a cruise, costs about $14,000, and one camera system at LSU is worth $250,000.

Plankton migrate from upper to lower water columns depending on the time of day, Sutor said, so it is important to keep an eye on them at all times.

She does not get much sleep on a cruise, she added.

“It’s a lot of deck work,” Sutor said. “It’s deployment and recovery, sometimes under dangerous sea conditions, and those were cases where I wanted to be out there.” Five years later, the spill’s effect on plankton is still unclear, and Sutor’s team continues to process and analyze samples.

She said results are difficult to obtain because scientists stopped taking samples too early, and she has little to compare her findings to.

“There have been almost no samplings of plankton in the offshore waters of the Gulf of Mexico prior to the oil spill,” Sutor said. “So we really don’t have historical data to look back to.”

While no major ecological collapses have been found after collecting a decade’s worth of research, Sutor said there is not definitive evidence that ecosystems in the Gulf are as healthy as they were before the spill. She said this is partly because the scientific community does not know much about the Gulf’s ecosystems.

Sutor took advantage of other sources of funding once BP stopped paying for expeditions in 2011, but the amount of research dropped off significantly.

“That’s what the tragedy is going to be, is we sampled for a certain time period after, and then we didn’t do anything and it became sporadic,” Sutor said.

Even after extensive collecting of plankton species, she said the scientific community will still have questions.

Sutor has several thousand samples shelved in her lab and another thousand being analyzed at other labs, which will be sent back to LSU. She said her plankton lab conducted some of the most extensive research in the years following the Horizon spill.

“I can’t think of another program that collected this many plankton samples in this amount of time as part of a single program,” she said.

LSU professor studies oil spill’s impact on plankton

By Sam Karlin

September 23, 2015

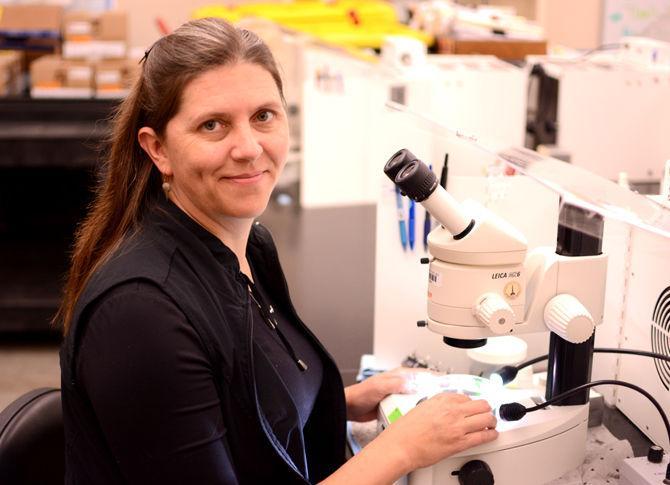

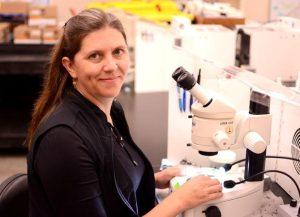

Coastal Fisheries Institute Assistant Professor Malinda Sutor has a “plankton lab” dedicated to researching offshore ecosystems.

More to Discover