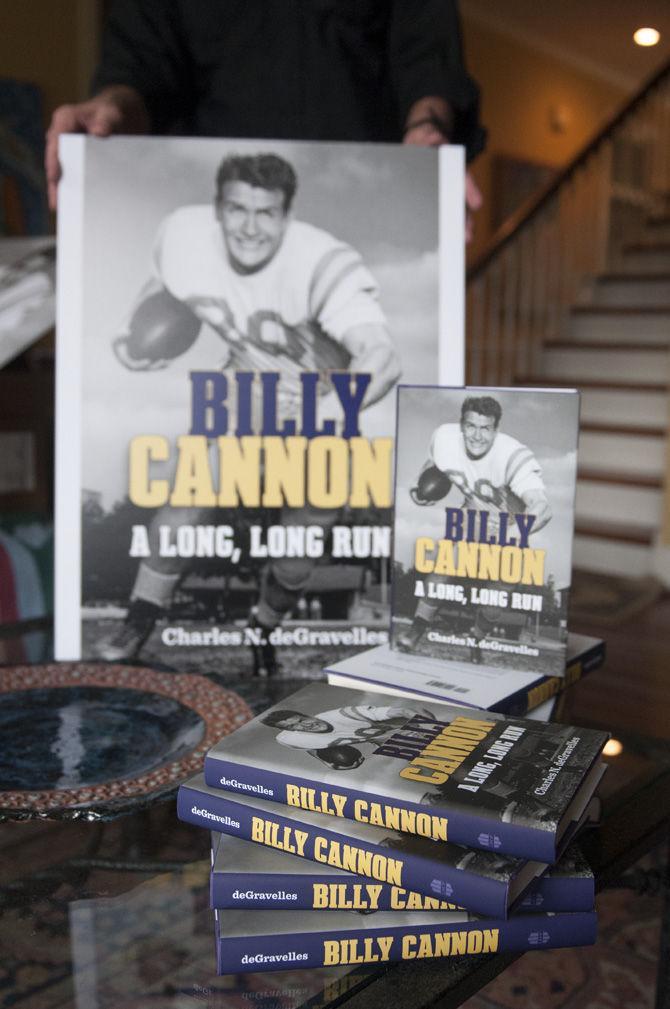

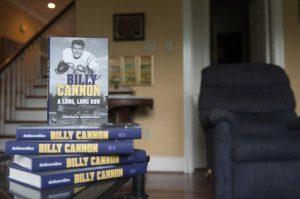

During the football season of 1959, all-star LSU running back Billy Cannon cemented himself in the university’s sports history when he won the Heisman Trophy after a college career unlike anything LSU football had seen before. Today, LSU Press author and deacon Charles deGravelles is bringing Cannon’s story to a wider audience with his first LSU Press novel, “Billy Canon: A Long, Long Run.”

The two first met at the Louisiana State Penitentiary, known as Angola, where deGravelles is a visiting pastor for death row inmates and Cannon is head of the medical program, and Cannon asked deGravelles to publish his story for the first time. DeGravelles said writers have asked for permission to write the biography for decades.

Cannon said that he chose deGravelles to tell his story because he liked deGravellles’ demeanor and genuine care for the students at Episcopal High School, where deGravelles works.

After growing up in a relatively low-income family, Cannon and his family moved to the Istrouma neighborhood in Baton Rouge during World War II at the end of the Great Depression. In high school, Cannon quickly became what deGravelles said to be the best football player in the country. He then went on to play college football at LSU, where he left his mark through triumphant victories and recognizable awards.

Cannon became more than just another football player for the university: He helped redefine LSU sports.

“The program brought the best players in, not only from Louisiana, but from Mississippi and Arkansas as well,” Cannon said. “There have been many great teams at LSU — we just happened to be the first to rejuvenate the tired program.”

Cannon said he’s regularly asked if his team could still be as successful today with the sport’s new regulations, and he maintains that many of his teammates, including safety Johnny Robinson and defensive end Mel Branch, could still thrive today.

However, he said the team’s linemen would be an entirely different story.

“When we were playing, there was no lock-in on weight,” Cannon said. “We had a lock-in on ‘try ability,’ and each of those players had unlimited ‘try ability.’ Those were the guys who showed up for every down and came back to practice ready to give everything they had. If they played today, a bunch of people would get hurt.”

Despite his successful professional football career, Cannon became a dentist after his Istrouma High School dentist Carl Baldridge inspired him. At the time, the dentist was the only one in North Baton Rouge. When Cannon nearly knocked a tooth out of his mouth, he went to the dentist to fix it. After many different visits and procedures, Cannon recalls never seeing a bill for any of them.

“When I asked the dentist why he never charged anyone for the procedures, he responded, ‘If I don’t, who would?’” Cannon said.

DeGravelles said it was Baldridge’s standing in the community and character over his dentistry skill that stood out to Cannon.

After starting a successful dentistry practice, Cannon’s downfall came when he counterfeited $6 million dollars in hundred-dollar bills, which became one of the reasons the story was kept quiet for so many years. Cannon’s counterfeited money, deGravelles said, was the product of an economic downturn as well as a “dark side” of Cannon’s personality.

“Part of [Cannon’s] personality makes him push the envelope. There was this part of him that loved to take risks, which got him into trouble in high school,” deGravelles said. “That said, if he could go back, he would never do it again, and he wholeheartedly regrets the event.”

Cannon served two and a half years of a five-year sentence before he was released. Because of his time in the penitentiary, he said Cannon lost his practice and had to find another alternative to practice dentistry.

This is the one part of the story Cannon wanted to make sure was told: his work with the Angola medical program. Cannon worked to develop and amend the program for 18 years. After those years, Cannon said he finally thought the program was in a satisfactory place.

With last year’s budget cuts, Cannon said that the program suffered some setbacks. But Cannon said he is still happy with the progress that has been made over the years and will be happy with the program when he decides to leave.

Cannon said he looks at his time at LSU and the Louisiana State Penitentiary through the same eyes.

“Players come, and players go, coaches come and coaches go, but great institutions last forever,” Cannon said. “LSU and the Louisiana State Penitentiary were both great institutions before and they will be after I leave them.”

The medical program’s story went untold until the book because Cannon mainly worked in anonymity.

“[Cannon] only wanted to excel,” deGravelles said. “While he did enjoy his fame, it was never something that he pursued, and he would go through great pains to make sure those around him received credit. Even at the prison he is there every day working with the inmates. It truly is remarkable.”

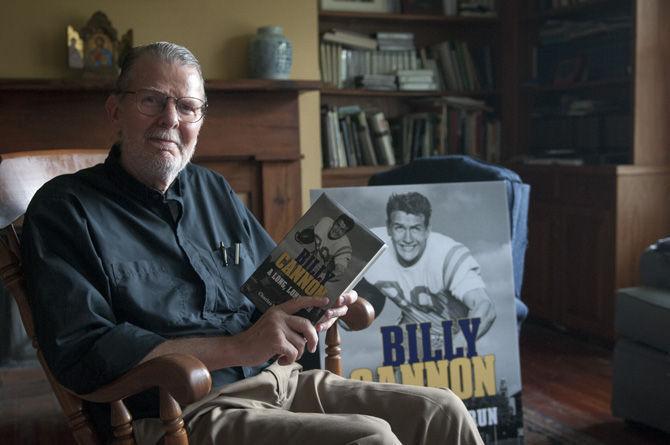

DeGravelles said writing the book over the course of a year while working full time was a challenge, but he is proud of the outcome.

Both deGravelles and Cannon are happy with the final product, but both of them wish there was more space for more stories that did not make the final cut. In order to tell these stories, deGravelles published them online to make sure the stories get the attention they deserve.

“Billy Cannon: A Long, Long Run” is available now on Amazon.com, and the official release is set for Sept. 7.

Football legend’s story published by LSU Press

August 31, 2015

LSU Press author and deacon Charles deGravelle’s recently published biography ‘Billy Cannon: A Long, Long Run,’ provides information about former LSU football player Billy Cannon.

More to Discover