Forty years have passed since filmmaker Les Blank filmed rock and roll star Leon Russell’s ascent to stardom.

Now in 2015, the documentary, “A Poem is a Naked Person,” is being given a widespread release, with a screening at the Manship Theatre on Friday at 7 p.m.

Admission to the Manship Theatre’s screening is $9.

The film follows then-rising rockstar Russel’s recording process in his Grand Lake, Oklahoma, recording studio from 1972 to 1974. The recording footage, mixed with live footage of Russell’s concerts, gives the audience a brief look into the private musician’s life behind the music.

Due to Russell’s closed nature, much of the film is filled with various clips of the band’s feet as they walk and other off-the-cuff interactions between the band and Russell.

Since the film’s soft release in 1974, the documentary has only been shown to a handful of people because of an assortment of issues, such as licensing problems with the music, Blank’s mandatory attendance at each screening and Russell’s general dissatisfaction with the film. A lawsuit was eventually created to ensure Blank never screened the movie anywhere but at nonprofit organizations.

These issues left Blank unable to promote the movie with anything but word of mouth, but he continued to edit the film over the past decades until producing a final cut in 2011.

But when he suddenly fell ill, one of his final wishes was to hand the movie over to his son Harrod Blank to remaster and preserve the film for the future.

“Les wanted me to remaster the movie regardless of whether or not Leon Russell approved of it,” Harrod said. “When the movie was released, Leon’s overwhelming dislike of the final product led to him not wanting anyone to see it. He was a rising star in the ’70s, and the movie only portrayed a small part of who he was, which is not what he wanted out of a movie he payed for.”

Harrod said Russell was a private person who rarely did interviews. Even during the film of the movie, Les did not have total access to the musician, leaving him with little choice but to fill the movie with different kinds footage normally left out of documentaries.

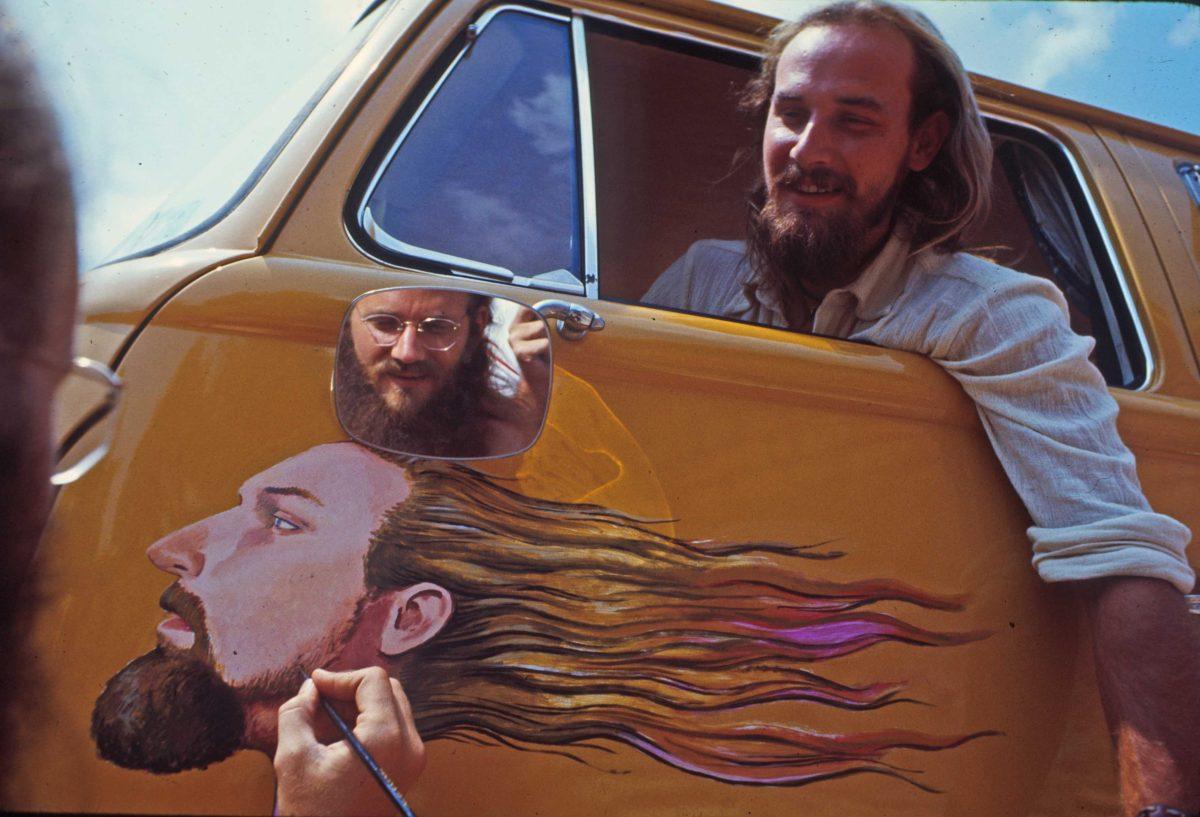

“People who walk into this movie expecting to see [Russell] talk about his music and his life are usually disappointed when they walk out of the film,” Harrod said. “This is not a normal ‘rockumentary’ by any means. It is like a time capsule of the time and place at Grand Lake with a Les Blank style on it.”

Harrod said Les had tried for decades to reach Russell to get approval to remaster the movie to no avail. Before Les passed away, he wanted to screen the movie at what was expected to be one final time with Russell present. When Harrod sent a message to Russell on Facebook, he was shocked Russell responded. Harrod said that while Russell could not attend, the message opened the door for further contact with the musician.

After Les’s passing, Harrod took over as executive producer to give the film a widespread release. Harrod said the two-year process has been worth it to fulfill Les’ wishes, as well as make the movie something Russell would approve of. Harrod said Russell has come around on the film, but there will always be aspects of it that he does not like.

“One thing that really cannot be changed that [Russell] does not like is the fact that he drinks and smokes cigarettes,” Harrod said. “Leon became an anti-smoking advocate, and he does not like that he smokes in the movie, but he looks at the movie as more of just a work of film rather than seeing his own part in it.”

While most of the film has been left as Les intended, Harrod said he has made some compromises and editorial changes to get the music rights for the film as well as improve how acceptable the film is to audiences.

“There was a raunchy rendition of “Lady Madonna” that we both could not get the music rights to, and we ended up cutting the entire scene because Leon didn’t like that it was disrespectful to women, and we both feel that it is a better movie without it,” Harrod said.

The final major change added to the film by Les was a scene depicting a conversation between Les and Russell about death.

“Originally, Les cut the footage because he thought it looked as though he was pestering [Russell], and he did not want to look like that,” Harrod said. “Given that Les has now passed, we felt that it would be poignant to add that they talked about death.”

Harrod said the entire experience of producing the movie was his life coming full circle.

As a child, Harrod spent time at Grand Lake while Les edited the film. Harrod spent a majority of his free time listening to albums Russell and Cordell worked on, and he drew pictures of Russell because Russell was one of Harrod’s childhood heroes.

Rock and roll film released by son, father’s final wishes

August 26, 2015

More to Discover