A big purple “1” rests on Tigers’ safety Eric Reid’s white football jersey. It’s only appropriate given the weight on his shoulders.

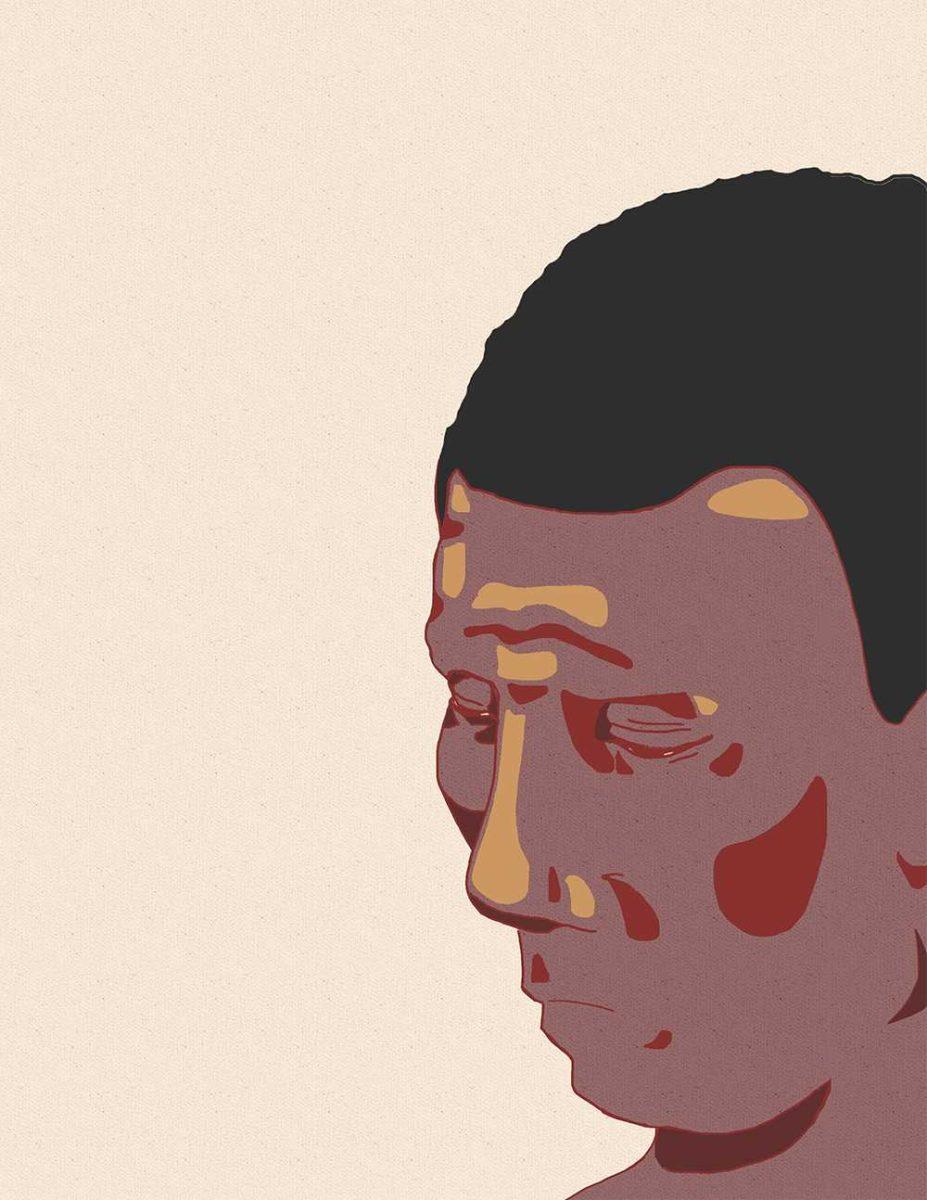

At 6 feet 2 inches and 212 pounds, the Geismar native is tasked every Saturday with destroying Southeastern Conference offenses with speed and efficiency as one piece of the LSU football team’s stacked defense. On the field in football gear, an intimidating helmet masks his handsome face, and his friendly demeanor turns into pure intimidation for offenses. As he perches at the back of the defense, alert and focused, he reads plays to tear them apart.

That’s why fans erupt into shrieks and howls as he appears on Tiger Stadium’s screens, and game announcer Dan Borné’s voice blasts over the loudspeakers, “At Free Safety, Eric Reid.”

But there’s a 3-year-old girl whose affection and reverence for Reid surpasses anything demonstrated in Tiger Stadium: His No. 1 — LeiLani Reid, Eric’s daughter.

Her small frame makes up the rest of his shouldered weight.

“You’re heavy, my shoulder hurts,” he joked with the little girl, who smiled as she sat atop his right shoulder.

On a visit to the LSU Football Practice Facility, LeiLani quietly sat in the corner of an end zone before her father emerged from the nearby weight room, immediately encouraging her to

hop up and sprint toward him.

“Let’s play football, Daddy,” she shouted up to Reid, tugging on his pants and gazing up at his towering figure. “We need a football.”

But Reid, management junior, isn’t the only Tiger with a cub. A number of athletes face the challenge of balancing athletics, academics and parenting — and embrace it.

Linebacker Lamin Barrow’s 3-year-old daughter, Laila, arrived when he started attending the University.

“Having her during my freshman year gave me something to strive for,” the sports administration junior said, noting his determination to succeed as a student and an athlete. “If there was any time that I got down and felt like I couldn’t do something, I’d just look at her — look at a picture of her, talk to her — to know what I’m working for.”

Reid agreed, describing the impact of his daughter’s birth.

LeiLani was born during Reid’s sophomore year at Dutchtown High School, where he also played football. And just like that, he said, a young man who needed unflinching confidence on the football field found himself with an unfamiliar challenge.

“It was scary,” Reid remembered. “I didn’t know what it was going to be like.”

Reid started working at Walmart after practices to help support his newborn. And with the support of his parents and then-girlfriend, he ensured LeiLani could grow up in a loving home. Of course, Reid said he also grew up in the process.

“I had to mature; I had to become an adult very quickly,” he said. “It was hard. She was a baby, and just like in the movies — they’re up all night.”

Then and now, his daughter provides the main fuel source for his efforts, Reid said.

“Life isn’t about me anymore,” he said. “[My decisions] have to be good ones for her. I try to do that and hopefully if God puts me in the right place, football will be a way that I can take care of her.”

And while it’s an increased responsibility, Barrow said being a father is fulfilling.

Though his daughter lives in New Orleans, he said she attends each home game to see her father play and spends Saturday night and Sunday morning with him before heading back for the week.

“Those kinds of things are the things you look forward to,” Barrow said. “I just get joy out of seeing when she sees me, and the way her face lights up and the way she runs to me. I just know that she knows her daddy, and I know her and I love her.”

But football season brings more schedule challenges for teammates with children, they said. Barrow and Reid, whose children live outside of Baton Rouge, said any time off the field is spent with their daughters.

“It’s definitely hard, sometimes I feel like I’m watching her grow up from a distance,” Reid said. “We use Skype, and I talk to her on the phone daily, but it’s definitely easier out of season … I look forward to Sundays because that’s when I get to go home and see her.”

While the road of parenthood is long and filled with challenges, student athletes have resources at the University to help them traverse it. One way is in the classroom.

Child and Family Studies professor Loren Marks pushes student athletes who take his courses to be champions on the field and at home as “championship parents.”

Marks, a husband, father of five and former basketball player at Brigham Young University, said he uses his own experience with family and sports to connect with his students.

“In the history of sports, no team or individual has ever won a championship by accident,” he said. “You have to be very focused and intentional in your efforts. Same is true in parenting. In this day and time, you don’t raise a great kid by accident — it takes a lot of work. I try to give them information they can apply in the real world that will help them.”

A large percentage of Marks’ classes tend to be student athletes, he said, including members of the football, baseball, basketball and track and field teams. Marks’ classes emphasize relationships between couples and their children as well as resource management, largely in money and time.

The focus on balancing sports and parenthood was introduced about 11 years ago, he said.

When Marks arrived at the University, he said he received an unexpected call from the Department of Athletics. He said the department recognized that several athletes had children and wanted these students to enroll in classes that would help foster strong family bonds.

“I’ve been impressed with the interest that LSU has shown in trying to help student athletes realize how important family is,” he said. “They called up and asked me, ‘These family classes you’re teaching, are they centered around real people? Real life?’ And I said, ‘Yes they are.’”

In these classes, Marks encourages his students to develop a family game plan. This involves journaling how to be responsible parents and family members. They discuss their vision for the future in terms of their connection with their children and what they want to give their children in life, Marks said.

Barrow said he enrolled in Marks’ class on family relationships shortly after Laila was born. While he wasn’t interested in the class at the time he enrolled, Marks ultimately became one of Barrow’s most memorable teachers, he said.

“[The journals] really helped me to express my feelings, the things I was thinking about with my family,” Barrow said. “It really helped me [move] that forward.”

Barrow said his team has also encouraged him along the way.

While football can consume their time, it also provides key support in athletes’ parenting. The sport inherently forms camaraderie, and this proves especially true among players who have known each other for years.

“Guys like Eric Reid, Tharold Simon, Craig Loston — these are guys I’ve come up with, and I’ve watched their children grow, and they’ve watched mine,” Barrow said.

This bond has helped during difficult times in Barrows’ life, he said. For example, he said, two summers ago his daughter became very ill, and he traveled to New Orleans daily after his classes and football obligations to watch over her. In addition to other players with children, coaches like Les Miles, John Chavis and Frank Wilson offered support and words of encouragement.

“To know all of those guys had my back and kept me pushing while she was sick, it brought me closer to this University, it brought me closer to these guys and these guys with these kids,” he said. “These are my brothers, and they feel what I feel.”

Correction: In the print edition, LeiLani’s name is misspelled in two instances.