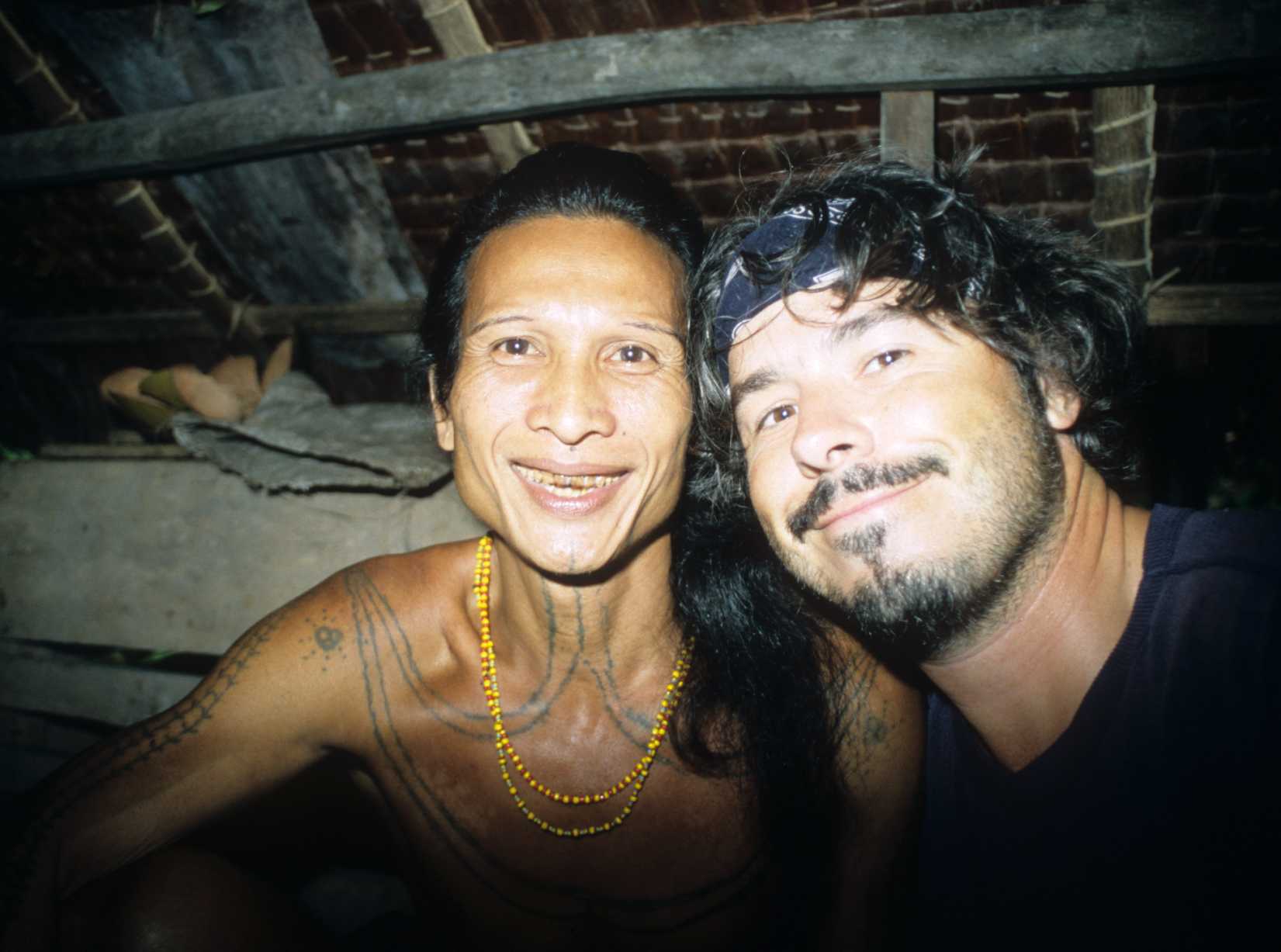

From arctic Alaska to Papua New Guinea, Lars Krutak keeps permanent memories of his travels to the corners of the globe in the form of indigenous tattoos.

The host of Discovery Channel’s “Tattoo Hunter” will present “Skin Deep: The History and Art of Indigenous Tattooing,” beginning at 6 p.m. in the Atchafalaya Room of the Student Union.

Krutak will begin with an encyclopedic introduction into the world and history of indigenous tattooing, followed by a segment on the magical and spiritual ramifications and meanings tattoos carry for the people who wear them. This piece will feature video segments from “Tattoo Hunter” to demonstrate to the audience how these cultures work.

Despite the varied natures of the world’s indigenous cultures, many use tattooing for similar purposes, Krutak explained.

“Practically speaking, a lot of people use tattoos cross-culturally for the same purposes even though they weren’t connected through any methods of communication or exchange,” he said. “It is a language, if you want to call it that. It’s a tool to communicate various things cross-culturally. Obviously, when you see someone with a tattooed face or other exposed body part, that’s the first impression you’re going to have of that individual.”

For many cultures, tattoos are also associated with rites of passage. They mark different periods of life and growth in maturity, beginning as early as 3 years old.

“It obviously transforms you physically but also spiritually,” he said. “I can think of many examples where, without receiving the mark of the tribe, you weren’t even considered to be human. You’re basically like an alien in some sense.”

But the first signs of tattoos were discovered in mummification. Krutak cited a 7,000-year-old South American mummy with cosmetic tattoos for beautification. And for several cultures, tattoos also serve medicinal purposes. Like acupuncture, tattooing was and is often used for sprains and arthritis.

“This therapy, if you want to call it that, was efficacious, and it worked,” he said. “Otherwise, people wouldn’t continue to do it now, 5,300 years after the ice man was running around in the European Alps with these medicinal tattoos and joint articulations.”

As a result of his interests in these traditions, Krutak himself bears various tattoos and body modifications from indigenous cultures he’s visited around the world.

“I’ve been getting all the traditional tattoos done,” he said. “I’ve basically had every technique that was ever practiced in the indigenous world, from hand tapping, to skin tattooing, to hand poking, to skin stitching, scarification — all of those methods, I’ve had.”

Krutak received his first tattoo from a friend in New Orleans in 1999. While this proved his only machine-made tattoo, it resembles St. Lawrence Island Yupic designs, an Alaskan culture that sparked Krutak’s interest in indigenous tattooing.

Krutak was familiar with tattooing because he previously lived around the corner from the famed tattoo artist John Ed Hardy in the Bay Area of San Francisco. When he moved to Alaska for his master’s degree, he encountered indigenous tattooing for the first time.

“I was walking across campus, and I came across this woman who was from a native village, and she had striped chin tattoos — I had never seen those before,” he said. “It wasn’t done traditionally, but it was done more to pay homage to her ancestors and her identity in that particular community. I began to explore a little deeper, and I found that it was a widespread practice across the arctic, but no one had really given it much attention.”

Krutak then found a group of women in their 80s and 90s with similar body work as part of this culture.

“I worked with those women, and they’ve all passed away, so I soon realized that this is probably happening all around the world in many remote regions,” he said. “So I sort of dedicated myself to documenting and preserving it.”

Fifteen years later, Krutak continues to help preserve indigenous cultures through his work at the Smithsonian as the repatriation case officer for Alaska and the Southwest United States. Here, he helps facilitate the return of human remains, sacred ceremony objects and patrimonial objects at the Smithsonian back to tribes who claim affiliation with these items.

“We’re giving back objects that have been at the museum for a long, long time,” he said. “Basically, I’m just trying to mend the circle and heal wounds that have sort of been long standing, and it’s a great job because I’m working with these people [Native Americans] on a daily basis.”