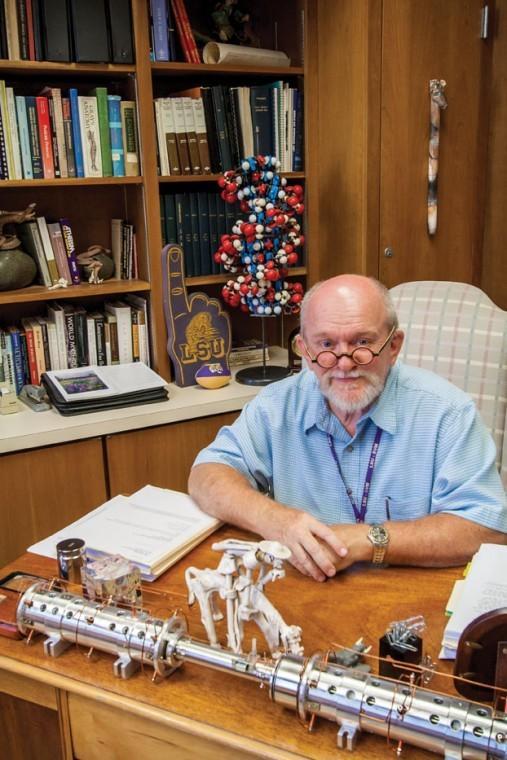

Professor Steven Barker is a curious, if strange, man. And he does little to hide it, if he does so at all.

With 28 years of work at the University behind him, this particular afternoon sees Barker smiling comfortably from the worn-in furniture in his office, his open-wide blue eyes betraying an eagerness to explain himself.

There is much explaining to do.

Every surface of his office in the Veterinary Science Building is bespattered by his youthful inquisitiveness with strange and intriguing curios. A large, marble mortar and pestle glows in the windowsill; a dusty three-dimensional model of a DNA molecule rests in the corner; awards and accolades adorn the homey wooden walls, which surround two exceedingly homey sofas; and atop his desk sits a cylinder from an outdated mass spectrometer — an intimidating device whose mystery is only exceeded by its price.

Though it looks like it would shrink one’s family or churn out superheroes with the flip of a switch, it is used to detect chemicals in focused samples, or quadrupoles.

“Pretty fancy stuff,” Barker laughed, and with a price tag that set the University back nearly $400,000 15 years ago, a dash of facetiousness doesn’t hurt.

All of these oddities would be relatively germane in regards to one another if left alone, but the tone of the scene changes with a glance at the man’s wall-spanning bookshelf. The topics addressed here range from molecular biology to philosophy to religious texts to atheism then back to more biology. And these topics couldn’t more fittingly summarize the mind behind Barker’s short, white beard and spectacles.

Along with being the director of the University’s Analytical Systems Lab in the Veterinary Medicine Building, Barker currently holds the position of State Chemist and works with the Louisiana State Racing Commission drug testing racehorses for steroid usage. But he stressed this work merely “pays the bills” and gives him the funds to pursue the motley interests bedecking his voluminous bookshelves.

Barker’s more acute attention is focused on the study of hallucinogenic substances, particularly dimethyltryptamine — commonly referred to as DMT. This substance has slowly crept to popularity over the past few years, partially due to the 2010 documentary “DMT: The Spirit Molecule,” which was hosted by actor and commentator Joe Rogan and featured Barker’s professional opinion.

But merely studying the effects of these substances is not nearly enough for Barker’s voracious curiosity.

“If you’re going to ask questions, you might as well ask the big ones,” he said, in excuse for the fact that the conversation had moved directly from pharmacology — the effects of drugs — to belief in God.

In collaboration with scientists around the world, Barker has been studying the pharmacology of ayahuasca, a type of tea preparation of DMT that has been used by various indigenous religious sects across South America for thousands of years. In these sects, the psychoactive substance is treated as a sacrament and is used solely (and strictly) for religious purposes. This highly common tendency among native populations, as Barker explained, makes sense when considering the so-called “religious experience” DMT is known to produce.

“[These compounds] cause euphoria, tunnels of light, they see fantastic beings — deities, relatives — you can’t explain it. Those phenomena … we know these compounds can do those things.”

Most shockingly, then, is the fact that DMT can be found in trace amounts throughout the human body, Barker said, from urine samples to blood to spinal fluid. And again, the implications therein are too grand for Barker to relax just yet.

“They’ve been around forever,” he said of psychoactive substances,

especially in regards to use for religious purposes. “It’s something that’s run throughout history.”

Barker also notes that people around the world have reported these experiences without actively administering the substance, which is to say that even acts such as deep meditation or sensory deprivation can generate religious experiences, seemingly from thin air.

But if DMT is so ubiquitous, what does that say about the similarly described religious experiences perpetually reported from around the world?

“Our understanding of perception is so minimal … Man has interpreted his hallucinatory experiences as being religious. There’s no question that people feel deep emotions when they undergo a religious conversion, [but] there’s a possibility we misinterpreted the entire thing.”

This idea has evolved into a budding field of study — and thought — known as neurotheology, denoting a biological and molecular basis for religious faith.

Recognizing the Latin phrase “deus ex machina” reveals oneself to either be a fan of drama, video games or Donnie Darko. In classical drama, deus ex machina signifies the turning point in the story when the day is miraculously saved by the whimsical gods of the day and age, and the phrase literally translates to “god from the machine.”

While it has been customary through the ages to blame the unexpected and unexplainable on divine intervention, Barker said he believes these phenomena can be sufficiently accredited to naturally occurring hallucinogens like DMT, which comes not from the gods but from our own bodies.

Neurotheology sets out to scientifically justify “creativity, dream states, near-death experiences” and various forms of hallucinations and religious experiences, and Barker thinks DMT could hold answers.

As a drug, DMT is much like serotonin, another compound naturally created by our bodies. Serotonin is a compound mostly involved with mood — though it is also involved with heart rate and other physiological functions — and elevations of serotonin levels can generate euphoria.

“Phenomena occurring without anyone on the outside being able to confirm it — that’s a hallucination. If a scientist watches a person undergoing a religious experience, well that’s serotonin,” Barker explained.

And these religious experiences and hallucinations engage the same areas of the brain we use for regular perception, Barker continued, which is why people think they’re real.

The search for objective answers to intangible experiences like hallucinations and dream states have intrigued Barker since he was a child. In his hometown of Birmingham, Ala., Barker said the religious faith of his community never quite sated his desire for clear answers.

“I always had trouble as a kid going to Sunday school,” he admitted with a chuckle. “‘Well, where did that come from?'”

He said the quest for more convincing answers began with his tendency toward intense dreams as a child — and dissatisfaction with the explanations he received to account for them.

“Most of the people who have experienced this kind of phenomena have relegated it to a religious experience,” he said. “I wasn’t able to accept it.”

For Barker, faith was never enough, and his desire for objective explanations persists to this day through his work.

For Barker, faith was never enough, and his desire for objective explanations persists to this day through his work.

“I find all of this far more exciting than just accepting someone’s belief. If you stop asking questions because you think you understand it all, you’ve made a big mistake,” he said. “Faith is not questioning — it intersects this whole field.”

Though certainly not late to this metaphysics party, Barker’s theory is not a new one. In fact, the term “neurotheology” was coined by famed British author and proponent of hallucinogenic substances Aldous Huxley, who used the term in his lesser-known utopian novel “Island” — the counterpoint to his revered dystopian novel “Brave New World.” In “Island,” Huxley uses the term to describe a marriage between human anatomy and a utilitarian approach to transcendent experiences, such as meditation.

At the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Barker said he was even lucky enough to become acquainted with British psychologist Humphrey Osmond, who supplied Huxley with the hallucinogen mescaline, which in turn inspired Huxley’s book “The Doors of Perception.” Osmond not only coined the term “psychedelic” but also gave rise to the idea of hallucinogens naturally occurring.

“Turned out that it was in …” Barker leaned forward and whispered, “everyone.”

The implications regarding the universality of DMT, perception and religion are massive, but Barker wouldn’t have it any other way.

“Our failure to understand things has led us down some dangerous paths. Understanding some of these things will really help us understand who we are,” he said. “Philosophically, it is a lot to wrap your head around. I’m not against religion, but let’s keep in mind there are thousands.”

Religious men and women around the world share similar religious experiences, Barker said.

“Fine, let’s look at the pharmacology of it,” he said. “Every state of consciousness can be connected to different areas of the brain being activated or deactivated. If we get an understanding of that, we may gain a better understanding of what the brain has to offer.”

There’s little room for glass houses in the world of neurotheology.

MAGIC MEDICINE

“Why do humans produce hallucinogens in their brains?”

Though this question posed by Barker remains unanswered, the number of scientists willing to approach it is slowly growing — and as it does, the taboo fades and more possibilities are realized, especially in medicine.

“Little by little their effectiveness is being realized,” Barker said. “It’s just the passage of time.”

No one seems to have aided this passage more than Rick Strassman, medical doctor and author of “DMT: The Spirit Molecule.” Between 1990 and 1995, Strassman conducted the first series of psychoactive substance tests on humans in more than twenty years, ending the embargo on such studies and opening countless doors to the future of psychedelic science.

“One of the things that came out of our studies was that you could give these drugs safely under medical supervision,” Strassman said. “That was a fundamental finding which I think sometimes escapes notice under the other data we noted.”

Strassman, like Barker, is also searching for that biological key to understanding the transcendental experiences shared by all humans — and he thinks the key to the question above could have been foretold millennia ago.

“I was always interested in the pineal gland as a possible spiritual organ, as it were,” Strassman said. “It’s always been an object of veneration in esoteric physiological systems — the anatomical location of high spiritual centers in Buddhism and Judaism.”

The pineal gland produces melatonin, a derivative of serotonin which affects our sleep and wake cycles, or circadian rhythms. It is no coincidence the pineal gland has also been referred to as the “third eye,” and directly linking this crucial part of the brain to the production of DMT could have huge results for the field.

“It would be icing on the cake,” he said. “We already know that the lungs make DMT — it seems as if the lungs are continuously producing DMT. It also seems the brain requires DMT for normal function.”

Finding DMT synthesis in the pineal gland would inject the hallucinogen into the everyday functions of the brain, and having written about this topic time and again, Strassman maintains that such a connection could finally rationalize and literally materialize the injection of the spiritual experience into the human experience.

“The pineal is quite protected from outside stimulation, generally, and the kinds of situations that overcome pineal protection are states of extraordinary stress,” he explained, listing common religious activities such as fasting and chanting as exemplary instances of great stress.

DMT in the pineal could be the keystone holding the weight of the field of neurotheology, tying a tight knot in the tangled ropes of spirituality and biology.

“It would validate all of these esoteric theologies that have been pointing to the pineal gland as a spiritual gland throughout history,” he said.

But Strassman stresses these findings say little about the existence of God, per sé, but offer more of a proof that spiritual experiences do exist and a reason to explore their anatomy further.

“You’re really not taking God out of the equation at all,” he said. “That’s why it’s called neurotheology and not theoneurology: This is how the spirit is working through the body rather than the other way around.”

While the clinical uses of such controversial substances as DMT, LSD and ecstasy are still being developed and explored, the simple credo of “science for the sake of science,” as Strassman put it, changes and advances the both the scientific and medical fields in the case of these chemicals.

The most important outcome is the removal of these substances from the Schedule 1 classification, thereby allowing them to be freely researched in the proper settings under the proper supervision, he said.

“Understanding the brain and the way the mind works is important,” Strassman reasoned. “I think it is important to apply psychedelic states for the greater good, and the greater good could just be increasing our database.”