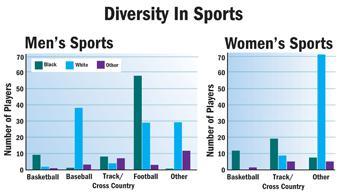

On Dec. 1, 1955, Rosa Parks disobeyed a bus driver’s request to relinquish her seat to a white man. April 4, 1968, was a date imprinted in the minds of many after Martin Luther King Jr. was struck by a bullet while on a balcony in front of his Memphis, Tenn., hotel room. During World War II more than 100,000 Japanese Americans were forced into “War Relocation Centers” across the country. Racial struggles have played a major part in American society, and collegiate athletics have followed the trend of separation. But some of today’s modern athletes look past one another’s skin color and cultural differences to “win as a team, lose as a team and breathe as one team,” said Ben Voogd, LSU men’s basketball sophomore guard. As one of only three white males out of 11 players on the LSU men’s basketball roster, Voogd said he has never seen himself as “the white guy” in a sport that consists mainly of black athletes. “We’re all just ball players out there,” Voogd said. “Coming from Oregon, where I grew up playing, there was no racial aspect at all. Maybe it’s different here in the South, but as long as the guys out there can get along and have chemistry, race should never be a problem. It shouldn’t be an issue at all because we’re one team just playing basketball.” Until the mid 1900s and especially when Loyola University in Chicago broke the gentleman’s agreement in 1961 not to play more than three black players at any given time, blacks were rarely allowed to play college basketball. Voogd said the integration process has helped college basketball get to the level it is now. “Back in the day, that was one of the best things that could’ve happened to sports – letting whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asians all play together,” Voogd said. “You’re giving a chance to the best players – no matter what race they are – an opportunity to further their careers while making the games more competitive.” Since the mid-1900s blacks, Hispanics and other races have continued to become more prominent in collegiate sports. Basketball, football, track and field and other collegiate sports have had major increases in the amount of minority athletes that participate in each sport. But white males continue to make up a large portion of one collegiate sport. With an almost 10 to 1 white to minority ratio during the Fall 2004-2005 academic year, LSU baseball coach Paul Mainieri said the lack of Hispanic, black and other minority players have hurt the game. “I would love to see more minority players in collegiate baseball,” Mainieri said. “I’m concerned about how it’s going to affect the future of the game, and it’s gotten to the point where Major League Baseball is worried about the lack of minority players in college baseball.” Mainieri said he thinks the background of a person has a great deal to do with why a prospective college athlete does not choose to play baseball. “A lot of these kids – especially black athletes – are coming from poor neighborhoods,” Mainieri said. “With having only 11.7 scholarships and only being able to give out partial scholarships, why wouldn’t a minority athlete go into a sport like football or basketball where he can receive a full-paid scholarship?” Freshman centerfielder Jared Mitchell, who is one of only two black athletes on the LSU baseball roster, said he would love to see more minorities in college baseball but said most minorities are attracted to football and basketball. “Baseball’s a hard sport to get in during the later years of your teenage life,” Mitchell said. “It’s all about what you’ve grown up doing, and I know a lot of young African-Americans love to play basketball and football – the sports where you get the fame and glamour straight out of college – and baseball is something you have to stick with. It’s not something where you can pick [it] up your senior year in high school and be good at it.” Mitchell added that most blacks are told by their peers not to play baseball because it is not the “cool” sport to play. Stevan Walk, former president of the North American Society for the Sociology of Sport, said the race of a student-athlete has less impact on which sport he chooses to play than does the student’s background. “I like to tend to avoid suggesting that certain races choose certain sports,” Walk said. “I have a problem with how individuals define race because it’s a social construction and should not be based on simplistic stereotyping based on a few simple visual characteristics of people.” Walk, California State University-Fullerton kinesiology professor, used Yannick Noah – the father of University of Florida junior basketball forward Joakim Noah – as an example to show how race is defined by a country’s beliefs and what individuals’ perceptions are of race. “[Noah] was a black man in France, but when he would get off a plane in Africa, he was considered a white man,” Walk said. “Which should tell us that race is something that is culturally defined, and it is not something that is biologically fixed.” Although racial trends in basketball, baseball, football and other sports continue to fluctuate, Walk agreed with Mainieri and Mitchell’s opinions that social class has tremendous impact on the sports students steer toward. “Economic class and access to sports has a lot to do with what individuals participate in,” Walk said. “If there is no money or political will to put baseball fields and other expensive facilities up in poor neighborhoods, then how are these children going to be introduced to these sports?”

—–Contact Jay St. Pierre at [email protected].

Black and White

March 14, 2007