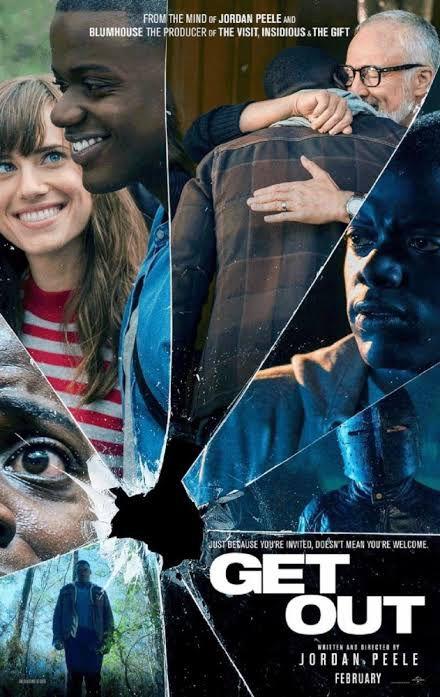

“Get Out,” the perfect film to counteract the torrent of Oscar-nominated tragedies, is a must-see in theaters, whether you like horror or not.

No one has ever been able to pull off what Jordan Peele did in “Get Out.” An ingenious satire for his directorial debut, Peele keeps the audience laughing while jumps, gore and plot twists abound.

Chris (Daniel Kaluuya) is a black man visiting the family home of his white girlfriend Rose (Allison Williams).

The conflict is obvious, with satire present from the beginning. As Rose insists her family isn’t racist, the joke is clear when her father, played by Bradley Whitford, insists out of nowhere he would have voted Obama into a third term and continuously calls Chris “my man.”

Early on, the film presents itself as a spectacle of white liberals trying their hardest to let Chris know they’re the good guys. It’s a take on the classic “I don’t see race” line.

The farce only grows from there. “Get Out” boasts a brilliant social commentary in which every line is imbued with subtext while maintaining its status as a hilarious yet horrifying thriller.

The concept that a black man is the protagonist and not the first casualty for a horror movie is revolutionary in itself and keeps with the movie’s honesty. The self awareness Chris shows, asking early on if Rose’s family knows he is black and whether her father will chase him off the front lawn with a shotgun, is what makes the film so believable.

It’s this self awareness and refusal to dumb itself down that makes Kaluuya’s character feel as if he is sitting next to you in the audience.

The unsettling feeling grows in your stomach as you see it appear on Chris’ face. There’s an honesty and practicality in the plot not often seen in horror movies.

For once, the protagonist seems to be cognizant of the situation he’s in. Instead of a demon-infested nun or children in a haunted school, it’s a black man stuck in the woods with dozens of white people.

The movie opens with a scene all too real: a black man, Dre (Lakeith Stanfield), is walking alone down an empty suburban street. A car pulls up, turns off its lights and begins to follow Dre — anyone can predict what happens next. Dre does too, but despite him muttering “Not today,” it’s too late.

The metaphor Peele creates with “Get Out” encompasses every key racial issue in America today, becoming more complex as the film goes on. It’s this relentless realism that makes “Get Out” so unsettling yet refreshing to see in theaters.

Along with its premise, the film’s comic relief and plot aren’t dependent on unrealistic situations like characters running down the stairs or unbelievably naive.

Peele’s timing manages to invoke comic relief without overshadowing the gravity of every situation. The whole theater laughs together, holds their breath together, then laughs again.

Chris’ best friend and dog sitter Rod (LilRel Howery) provides more than just comic relief, telling Chris what everyone in the audience is thinking. “Don’t go to a white girl’s parents’ house!” Rod yelps through the phone.

There are few true jokes in the film, despite how often it causes viewers to laugh. The absurdity and accuracy of situations like Rose’s family hosting a party of nearly all white guests, with a golf pro suggestively telling Chris “I know Tiger” and the only other black man shaking Chris’ fist bump create enough hilarity.

It’s in these scenes that Peele’s handiwork is most familiar. Known for his sketches on “Mad TV” and Comedy Central’s “Key and Peele,” he has a long history of racial satire.

While stomach-churning horror is new for Peele, he manages to turn the horror genre on its head by keeping to what he does best.

Taking the notion of stereotyping and cultural appropriation to another level, one not wholly unrealistic either, is Peele’s reinvention of the genre that can usher in a new era of horror movies.

Rev Ranks: “Get Out” turns horror genre on its head

By Ryan Thaxton

March 1, 2017

“Get Out,” a horror film written and directed by Jordan Peele, was released Feb. 24. The film tells the story of a young African American man visiting the family home of his Caucasian girlfriend.

More to Discover