Since 1980, a cold case – involving several of the University’s most notable historical players – has loomed over David Boyd Hall, the University’s art collections and LSU history enthusiasts.

Four paintings were stolen from David Boyd Hall just over 37 years ago, and the pieces of LSU’s history have never been recovered. According to a story in The Daily Reveille written days after the break-in, the thieves sliced the works of art from their frames in the evening of Sunday, March 30, 1980.

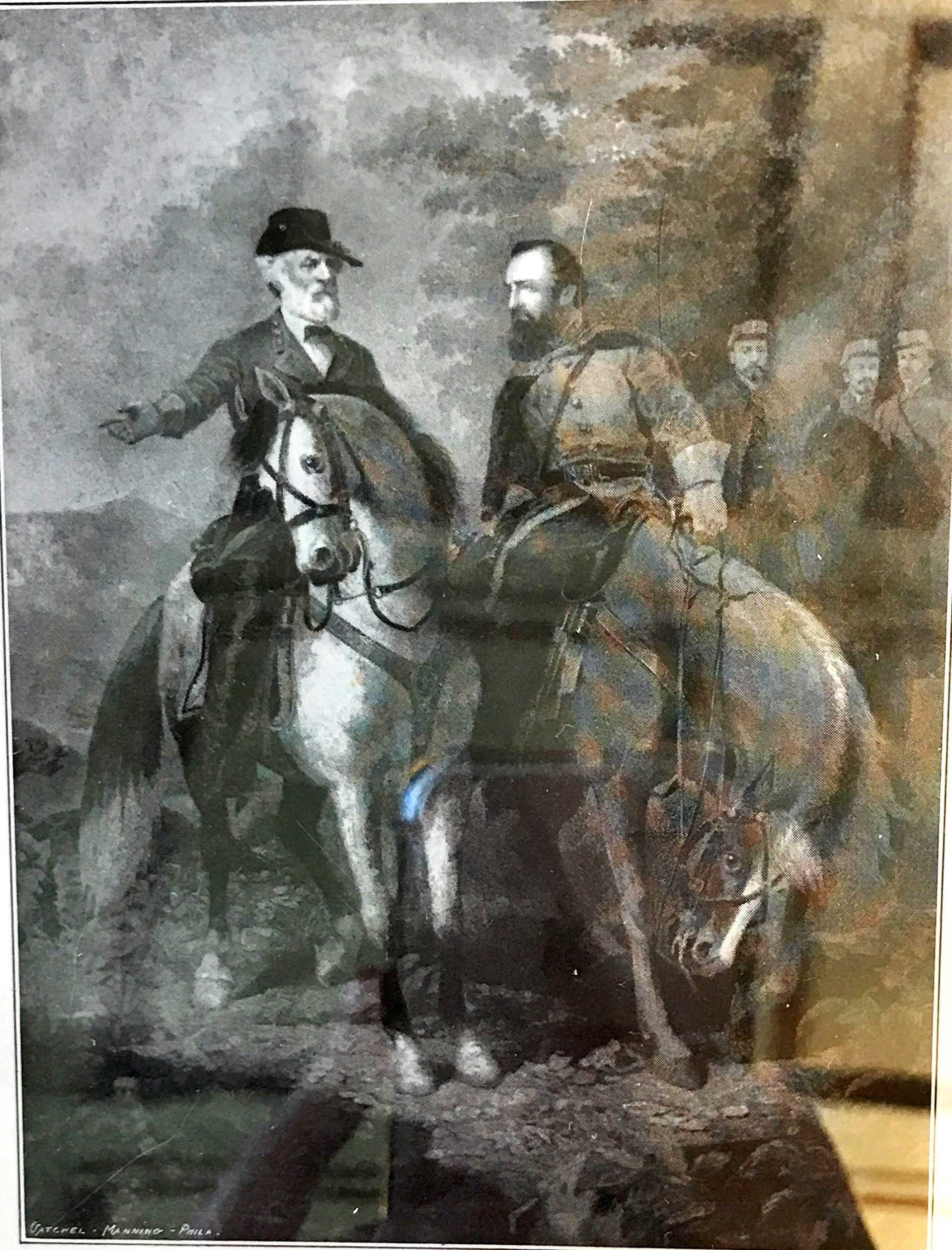

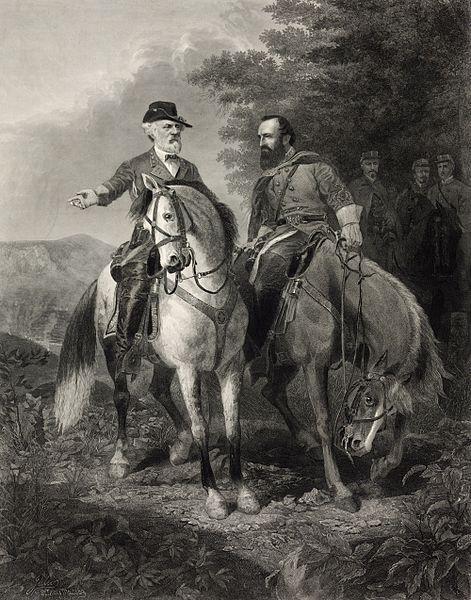

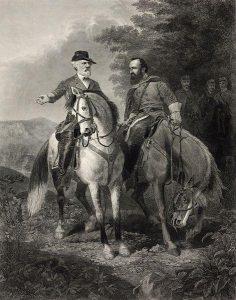

The four paintings are of great historic value to the University. The first was “The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson” – an original copy of the famous painting hanging in the American Civil War Museum in Richmond, Virginia. According to University Archives, Col. David F. Boyd, the first president of the University, persuaded the original artist, Everett B.D. Julio, to paint a copy in 1869.

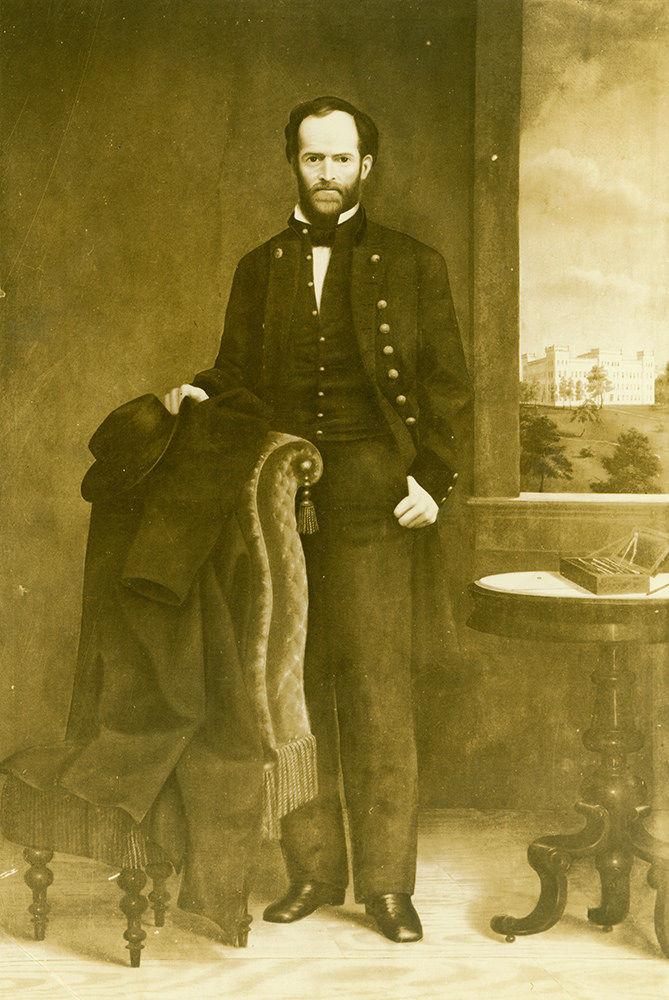

Two of the paintings, done by the University’s first engineering professor, Samuel H. Lockett, are large-scale portraits of two larger-than-life figures in LSU history – Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and George Mason Graham. The portrait of Graham, who was the first Board of Supervisors president and called “The Father of LSU,” was a full-length portrait painted in 1870. Both the portraits stand more than seven feet tall.

The full-length portrait of Sherman, the first superintendent of the old State Seminary at Alexandria and Civil War hero, was painted by Lockett while he was the commander of cadets at the seminary. The painting hung over the mantelpiece of the seminary’s library until the building burned in 1869. A group of cadets, which included a young Thomas Boyd, saved the painting from the blaze.

The painting was done after Sherman, as a Union general, had scorched the southern earth during his famous “March to the Sea.” But his friendship with Louisiana military men remained, and it was Sherman who intervened on behalf of David Boyd after he was captured by Union forces.

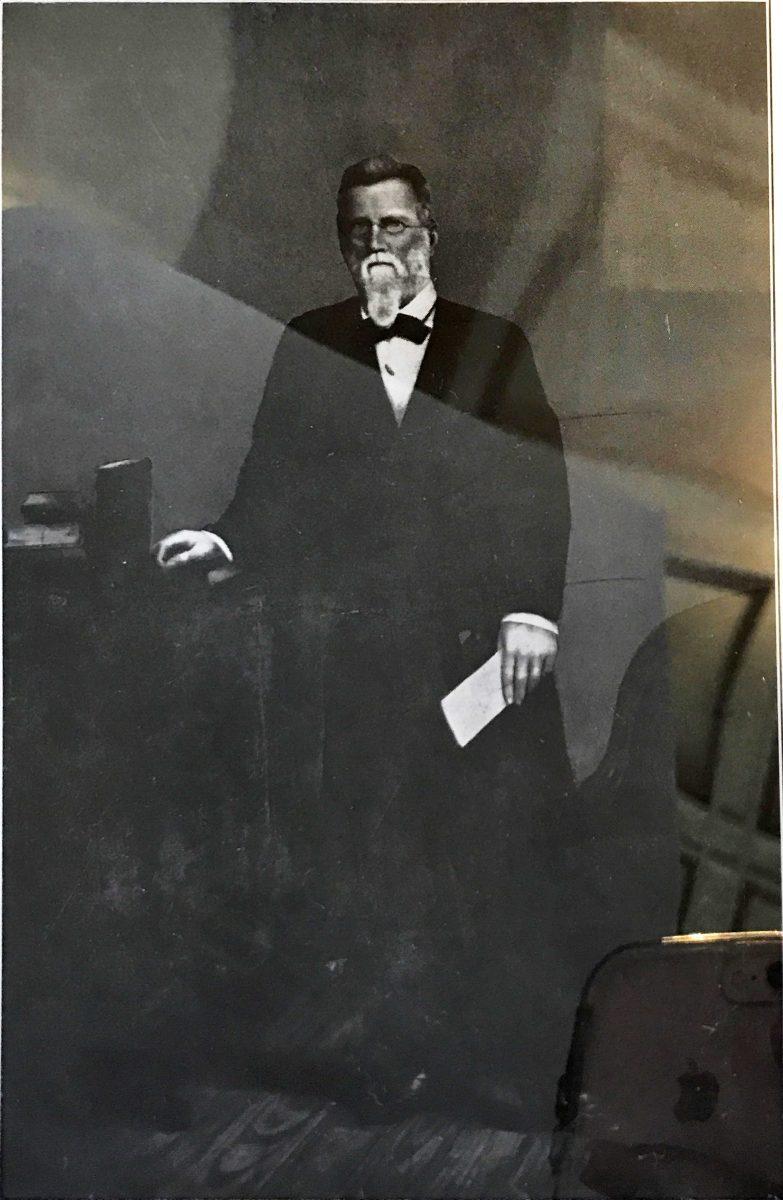

The fourth painting featured Dr. George King Pratt, a medical doctor from St. Landry Parish who lived in New Orleans. He was the leading member of the Board of Supervisors from 1900 to 1906. The portrait was painted in 1920 by C.J. Fox.

Henry P. Bacot, who served as the LSU Museum of Art’s director for 33 years and retired as professor emeritus in art history, described the theft as a terrible loss and fears the stolen works were destroyed after the FBI was brought into the investigation.

“The FBI got involved and all kinds of things, and I think that could have scared people,” Bacot said. “They could’ve thrown them over the levee into the river, or they could have burned them. You just don’t know.”

In Bacot’s opinion, the thieves were likely not professionals – possibly students or thieves with general knowledge of the paintings. According to the Reveille archives, the burglars broke into Himes Hall through a window and stole approximately $30-35,000 of video equipment. According to the archives, the paintings were collectively worth approximately $50,000 at the time.

The thieves crossed over the portico which connecting Himes to Boyd. According to the Reveille archives, Oscar G. Richard III, the then- LSU Media Relations director, and James W. Reddoch, the vice chancellor for student affairs in 1980, suggested that the crime had a “touch of professionalism,” as the thieves would have needed a van to carry off the equipment and artwork.

Following the theft, then-chief of LSUPD Gary Durham wrote Reddoch lamenting the general lack of security the University.

“I can assure you that even with the aggressive crime prevention/building security program the police department started some six months ago, that few campus buildings are properly secured,” Durham wrote on April 9, 1980. “Our officers can check and secure a building at one time and recheck it 30 minutes later and find doors and windows open.”

Bacot holds out hope the paintings are still intact, sitting somewhere safe. He said “The Last Meeting of Lee and Jackson” is most valuable monetarily. He said it would likely sell for close to $200,000.

The portrait of Graham, while only worth a couple thousand dollars, is probably the most valuable to the University, Bacot said. According to the archives, Graham carried the University through some of its most difficult days – the Reconstruction period.

“If you know your LSU history, you know that George Mason Graham was the glue that held the university together after the Civil War,” Bacot said. “That painting is very important, and he should be well remembered.”

A fifth painting – also done by Lockett – was severed from its frame, though it was left behind. The painting was a half-portrait of Gervais Baillio, a member of the first Board of Supervisors. He was also the son of the Rapides Parish pioneer Pierre Baillio, whose house was restored in Alexandria and stands as a museum and is representative of the early French culture in central Louisiana.

While the majority of current University students and faculty and recent alumni may be unaware of the paintings’ disappearance, the theft made waves at the time. The April/May 1980 edition of the LSU Alumni News included a posting for a reward totalling $10,000 through LSUPD.

Though such a long period of time has passed since the crime, and despite his theory that the paintings have been long since destroyed, Bacot remains optimistic that the paintings are still safe.

“There’s always hope that somewhere they’re being saved,” Bacot said.

Lost Art: Stolen paintings of historic LSU figures still lost after nearly 40 years

April 6, 2017

The full-length portrait of George Mason Graham by Samuel H. Lockett was stolen from David Boyd Hall in 1980.