Walking around campus, we pass hordes of other students every day. What we see are students like us: stressed, sleep deprived and each moving step by step toward their goals.

If we could see past the outward appearance, we would see the individual struggles beneath the surface.

In 2016, over 2,000 students on the University’s campus dealt with specific kinds of struggles every day in the form of a disability. According to Director of Disability Services Benjamin Cornwell, a large majority of these students are people whose disability is not apparent upon a first or even second glance.

In fighting through their disabilities and the challenges that accompany them, there is a sense of empowerment and an invaluable self-worth to be found should they choose to embrace it. Several University students shed light on their disabilities and how those disabilities make them stronger.

Matthew Klotz

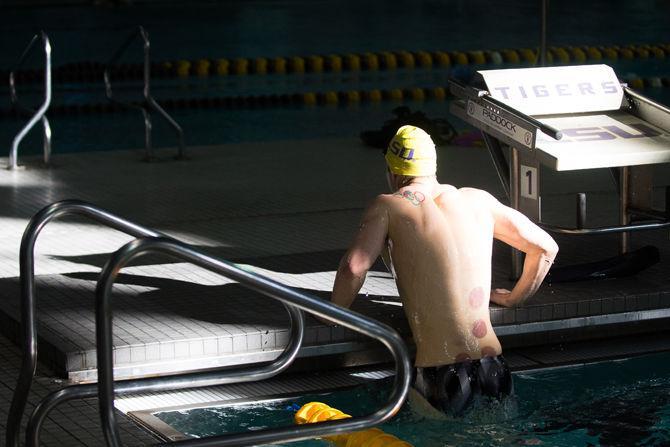

As kinesiology sophomore Matthew Klotz pushes his upper body out of the pool, we get a glimpse of five colored rings tattooed on his right shoulder. However the middle ring of the Olympic symbol is not its customary plain black, but rather a gear-like symbol with red, blue, green and yellow fingers spinning out of it.

Klotz explains this is the symbol for the Deaflympics, an international event which takes place every four years for deaf athletes. In 2013, Klotz represented the United States in Bulgaria at only 16 years old, where he set the Deaflympics record for the 100 meter and 200 meter backstroke. Since then, he’s earned 11 American deaf records as well as a few deaf world records.

Klotz is currently looking forward to attending his second Deaflympics this year in Sansun, Turkey.

Klotz started swimming at the age of four, when he was also going through speech programs to learn how to speak as a deaf child. Because of these programs, Klotz is able to speak clearly and easily today, despite his lack of hearing.

His hearing aids help him to engage in conversations and interact with the hearing community relatively easily, but they can’t help him in the pool.

“I can’t hear coaches talking to me. I can’t hear people cheering. I can sometimes hear the buzzer but not the ‘take your mark’. It’s hard because it takes my focus off of the race, watching other people to know when to start,” he says.

Despite these struggles, Klotz is currently building a successful swimming career at the University and says he is loving every minute of it.

“My plan is to one day be able to get the actual Olympics symbol on the other side,” Klotz says of his tattoos and his dreams. “There’s a lot more work to be done, but that’s the big goal.”

Justin Champagne

Physics and computer science junior Justin Champagne carefully makes his way down the stairs, using a cane to feel where the next step is. When he makes it to the bottom, he folds it up and greets me with a big, bright smile.

Champagne’s cane makes it easier for him to get around campus with limited sight. He suffers from a condition known as Retinitis pigmentosa.

“What it basically in a nutshell means is I have no peripheral vision,” he says. “I can see you just fine if I am looking directly at you, but say I turn my head this way, you’re gone — disappeared.”

Champagne says he doesn’t find his disability confines him in any major ways. His main challenges are reading small or far away print, which is a challenge that Disability Services assists him with academically.

“They do really great work,” he says.

Champagne also struggles to get around in the dark, and has discussed improving on-campus lighting at night with University architects.

Retinitis Pigmentosa is a condition that is sometimes degenerative. The possibility of losing his sight for good is a daunting one for Champagne.

“It definitely scares me,” he says. “As I am right now I am not prepared. It would mean a lot of changes, but if worst comes to worst I’ll be fine.”

Whatever happens, Champagne doesn’t plan to allow his disability to stop him from his dream of pursuing a Ph.D in physics and one day becoming a professor. Today he is already working toward this goal through vigorous studies and his job doing undergraduate research in the physics department.

Ashley Landrieu

Theater performance junior Ashley Landrieu says she always thought she was stupid. But, she later found out she struggles with learning disabilities dyslexia and dyscalculia.

Dyslexia is a disorder that affects language processing skills that can inhibit oral transmission, reading and writing. The condition impacts each person differently, but for Landrieu it means many extra hours spent reading the plays she is assigned almost nightly. It also means that reading out loud in class is something she dreads, as it involves stuttering and struggling through simple sentences.

Dyscalculia is a disorder similar to dyslexia, but one that makes understanding the concept of numbers more difficult. Landrieu says doing simple math problems in her head can take an enormous effort and length of time.

“I remember once in discussion about my dyscalculia, my friend asked me to calculate 400 plus 200. I could not get it in my head. It took 10 minutes for me to get 600,” she says.

Despite struggling through reading assignments and frequent table reads, Landrieu loves her major.

“It’s hard to feel stupid in this building,” she says. “People are always running around, singing and dancing in the halls. You can talk to anyone. It’s a positive environment to be in really.”

She says that ironically, her disability has actually granted her above average memorization skills, a valuable asset to have in theater.

In growing to understand her disability, Landrieu has grown to understand and accept herself.

“I’m not stupid at all,” she says. “I am different. No one is perfect and I wish I had spent less time trying to be perfect, and more time just trying to be me.”

Amanda Swenson

Ph.D. student Amanda Swenson laughs as she recounts the scene in “Alice and Wonderland” where Alice finds her body growing incredibly large or shrinking so small she falls into a bottle and says the book was actually written about symptoms of epileptic seizures.

“I have actually had those types of seizures,” she says. “They’re super weird. I won’t say they’re not fun… they’re just weird.”

Swenson was diagnosed with left temporal lobe epilepsy at 18 years old.

“I was originally pursuing opera,” she says. “That was my one true love, singing, and I had to give it up. And it was really hard.”

Swenson still engages in her love of music with her violin, an instrument she’s played for the past 24 years.

She’s spent time at Earl K. Long Hospital in New Orleans receiving treatment. It’s also the place where her world was opened to countless stories of impoverishment, illness and disability that went on to affect her life and work.

“What I try to remind people is to always remind yourself that illnesses and disabilities are spectrums and to never assume that because I’m feeling this, the next person is as well,” she says.

Today she studies disability alongside animal studies and postcolonial studies, and takes part in organizing the Disability Student Organization at the University, aimed to provide a community for and give voices to disabled students on campus.

Swenson wants to promote a new understanding of disability, with all of its intersectionality and facets.

“I think understanding all of the tensions and waves that come along with disability is important, tensions of disability pride, of taking agency over your body, tensions between visibly disabled people and non-visibly disabled people,” Swenson says.