Lora Hinton’s journey to Tiger Stadium involved politicians, a few semesters on the sideline and, much to his dismay, some unfamiliar seafood options.

In the fall of 1971 the dining halls would deem Fridays “fish day” and, of course, the most popular serving of fish was crawfish. As Hinton watched students peel, eat and suck the heads off “mud bugs,” he was in disbelief.

“Are you kidding me? People actually eat these things?” Hinton said. “We see them in the ditches where I’m from … I couldn’t handle the menu.”

For the Chesapeake, Virginia native, learning about unfamiliar foods was only the start.

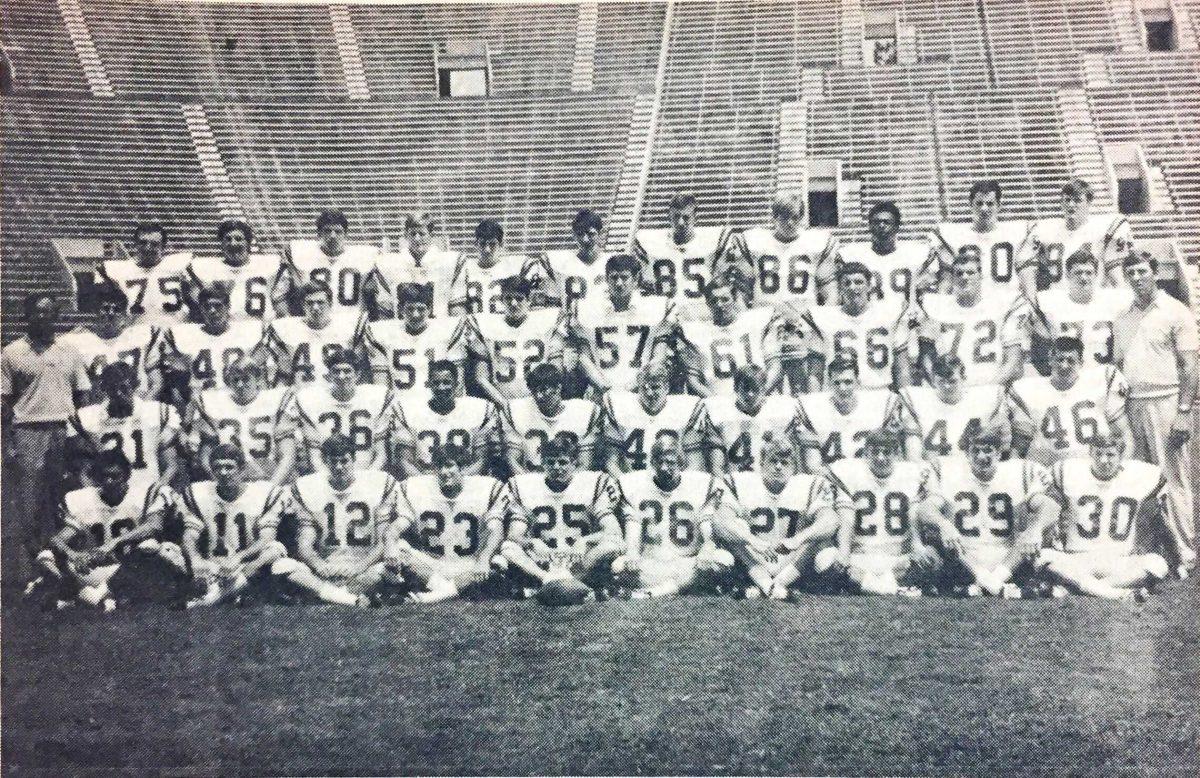

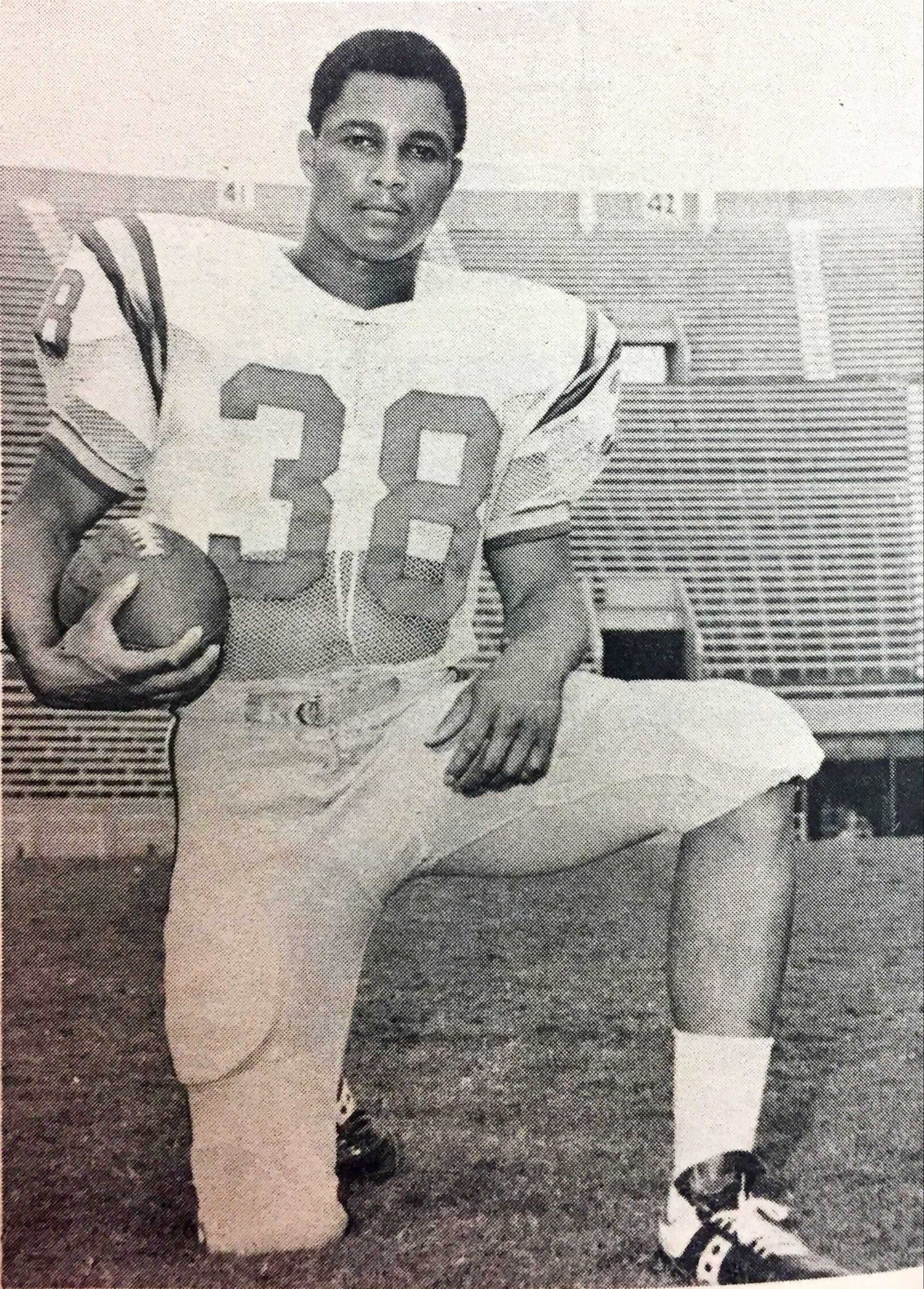

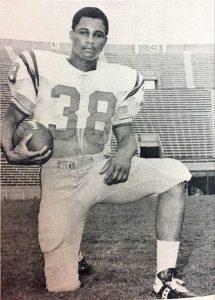

The fall of 1971 began Hinton’s trailblazing path, when he and Mikell Williams became the first black football players to receive scholarships to play for LSU.

For Hinton, the allure of playing at LSU was bigger than staying on the east coast near his small hometown.

Breaking another barrier

Attending LSU wasn’t Hinton’s first time serving as a pioneer at a school.

He broke down a barrier at Great Bridge High School, in Virginia, as the school’s first black student.

“It prepared me,” he said. “No doubt.”

Hinton later found his way on the football field at Great Bridge, where he became an All-American. His film wound up in the hands of coaches at Notre Dame, Penn State and Purdue, to name a few.

But he suffered a knee injury during his junior season and played only one game his senior year.

“Back in those days, when you had an ACL problem, that was pretty much the end of your career,” Hinton said.

However, his talent was too good for coaches — and a Louisiana politician — to pass up.

Former Louisiana Gov. John McKeithen — a fan of LSU football — saw Hinton’s film and decided to help recruit him.

McKeithen even invited Hinton to eat breakfast in the Governor’s Mansion while he was visiting LSU.

“It was pretty cool,“ Hinton said.

Hinton knew he wanted to play football in the South, and LSU was the perfect fit.

“There were some questions,” Hinton said. “After I made the visit, there was some guys who took me around, made feel comfortable, and I felt like this was a place I wanted to be.”

But there were reservations about Hinton going to school 1,114 miles away from home. His father wanted him to go to a service academy, northern coaches didn’t want him to leave the east coast and his mother was scared.

“What really made it bad — a recruiting coach from one of the northern schools suggested to my mom that there was a possibility that I could get knifed if I came here for school … It was just a bad deal to throw down on a high school kid.”

New kid on campus

In the ’70s, freshmen weren’t allowed to play their first season.

Tiger Stadium was smaller back then. But to Hinton, the crowd roared even louder than it does today.

“I can remember being in the ‘chute’ right before the team walked out and somebody opened the door,” Hinton said. “I was able to look out onto the field, I was like ‘Man, that looks like television’ when I walked out there.”

Hinton went from watching LSU play against Nebraska in the 1970 Orange Bowl to working out among some of his idols.

“Being in the locker room working out and I see Jerry Stovall walk in the room,” Hinton said. “I’m like, ‘What is this?’ and he’s my coach. A friend. A mentor. Being a part of LSU, I got to see what it was about. Those were the good ol’ days.”

But Hinton’s knee problems followed him to LSU.

He spent his first six weeks on campus on crutches after he had knee surgery. Hinton also redshirted his sophomore season.

“I was hungry, and I wanted to play,” Hinton said. “I wanted to contribute. I had to wait two more years before that would happen.”

There were some isolated incidents in which opposing players made derogatory comments, but Hinton said that mostly “was not happening.”

As LSU was actively searching for more black football players, Hinton’s sideline contributions came in the form of hosting black recruits when they visited campus.

“They didn’t know me, because I hadn’t played,” Hinton said. “Everybody knew about Mike Williams. He was a great ball player. Whenever people approached me, they thought I was Mike Williams.”

But Hinton and Williams took two different paths.

Williams, a Covington, Louisiana native, became an All-American and eventually a first-round NFL draft pick.

Hinton would end up lettering at LSU for three years but seldom playing.

The once and a lifetime experience was something Hinton said he would never change. By playing football at LSU, Hinton helped bring more black players to Tiger Stadium.

“We had 100 some guys who came from over the nation just to walk-on,” Hinton said. “Knowing they wouldn’t make the team, but they just wanted to be there. Being able to be a part of that experience and being around guys … I kind of feel like I got something that nobody has.”

Lasting Legacy

Four decades later, Hinton is still a part of the LSU community. He hasn’t left Louisiana and now indulges in Louisiana cuisine — including crawfish.

On Saturdays in the fall, Hinton works as a game marshal, a job he’s done for the last 24 years.

He said seeing LSU and black athletes excel makes him “proud.”

“It’s really cool,” Hinton said. “I guess that’s the best way I can sum it up. Those guys are great and you want to see them do well, that’s all.”