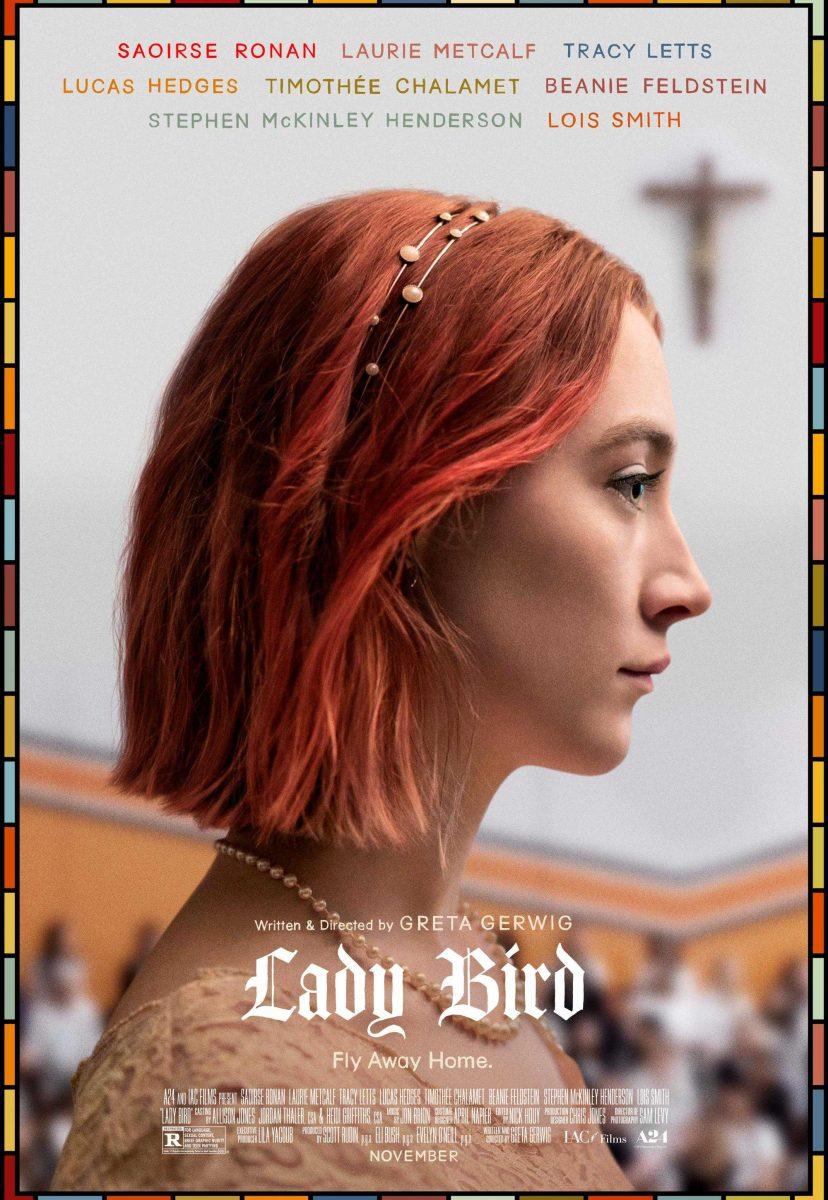

STARS: 5/5

Although it’s often easy to forget due to the excess of unoriginal and drab examples that come to mind, there’s good reason that the coming-of-age story is one of the most overdone genres in film. Every year a movie comes along so original, joyous and humane that we remember why we love watching other people experience the same highs, lows and pains we all have. In 2017, Greta Gerwig’s directorial debut “Lady Bird” is that film.

Described by Gerwig as one person’s coming of age being another person’s letting go, “Lady Bird” is a love story between a mother and high school senior Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) as she navigates through first loves, the tribulations of friendship, financial struggles and an overbearing hypercritical mother (Laurie Metcalf). It’s also so much more as it tackles class, sexuality, happiness, family and life with a dual sense of normalcy and eloquence. Put simply, “Lady Bird” is the best film of 2017.

The tone is set from the opening: Lady Bird and her mother are barreling down an endless California highway post college visit. They’re listening to the last few sentences of an audio recording of “The Grapes of Wrath,” both in tears, sharing a quintessential mother-daughter moment. One thing leads to another and two minutes later, Lady Bird jumps out of the moving vehicle, breaking her arm. With this, we’re immediately thrown into the beautifully absurd lives of a mother and daughter both on the verge of a new life: college for Lady Bird and a (somewhat) empty nest for her mother.

Lady Bird is ready to leave her quiet hometown of Sacramento in exchange for a place where she can “live through something,” like New York, while her mother, Marion, wants her to stay close to home. Marion says it’s because her family — whose patriarch just lost his job — can’t afford out-of-state tuition, but it’s in her subtle nuances and gazes that it becomes obvious she’s afraid to let go.

Depictions of mothers and children grappling with the onset of college are nothing new, but it’s never been handled quite like this. That’s because as humans, we often feel complex and contradictory emotions in moments of high importance, and in “Lady Bird” Gerwig perfectly captures that sensation, as well as the difficulty of handling those feelings.

Just like how “Lady Bird” handles the treatment of the setting, Gerwig’s own hometown, Sacramento, Lady Bird and Marion’s feelings toward this new chapter of their lives are clothed in ambivalence. And even though Lady Bird consistently complains about Sacramento, the scenery is bathed in golden-hour sunlight, making “the Midwest of California” seem poetic at every turn.

It’s not just in the humane portrayal of major life events that “Lady Bird” is a winner, but it’s also in Gerwig’s sophisticated and hilarious script. Exchanges between characters excite us as we wait for the next quip or 2003 pop culture reference to appear. Her script plays out like the best conversations — those that make us feel valued and important. The normalcy of it all makes it easy to follow and to enjoy, but there’s enough profundity to satisfy even the worst of film snobs.

The two main performances are revolutionary turns from extremely talented actresses, Ronan on one end and Metcalf on the other. Ronan, with her pink hair and acne-ridden skin, brings warmth and electricity to Lady Bird. Metcalf steals scene after scene with her combination of hard and soft, and in her last appearance it’s obvious she’s destined for an Oscar.

The likability of the film only increases with each new supporting character, all impeccably played by the respective cast members. Lady Bird’s best friend Julie (Beanie Feldstein) is the best of these, putting on a happy-go-lucky shell to hide her deep-rooted insecurities and her search for validation. In one heartbreaking scene, she tells Lady Bird, “Some people aren’t built happy,” a quiet dedication to teenagers struggling with bouts of depression and other mental disorders — a topic addressed in other aspects of the film as well.

Lady Bird’s two love interests (Timothée Chalamet and Lucas Hedges) play their respective roles with confidence and depth. In “Lady Bird,” no one is really whom they seem to be on the outside, and these two men — among Hollywood’s best young actors — do a brilliant job revealing their layers.

Ultimately, what’s so special about “Lady Bird” isn’t that it tells a revolutionary story, but that it finds the sublimity in day-to-day life. It makes us look at the places and the people that made us, and it gives us eternal gratitude for these places and people. Watching the film is a cathartic and joyous experience that isn’t just for mothers or for daughters; it’s for humans. And us, as humans, are lucky to have a film like this.