On Sept. 28, 1969, three hunters were giving their dogs a field workout in a wooded area just five miles from the University. At 10:30 a.m., they found the body of 18-year-old University freshman Daniel Austin Sistrunk hanging from a tree.

According to a report in The Daily Reveille in September of 1969, Sistrunk, who had been missing for more than a week, had climbed a tree and leapt with a sash-cord tied around his neck.

On Sept. 29, 2017, the remains of sociology senior Michael Nickelotte, who had been missing for over a week, were found in the woods off of Nicholson Drive. Nickelotte died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, according to East Baton Rouge Parish Coroner William “Beau” Clark.

Forty-eight years and one day before Nickelotte was found, Sistrunk was the first of six University students who would commit suicide between September of 1969 and May of 1970. One of the six to pass away that academic year was law student and LSU Student Government president Art Ensminger.

Ensminger had been elected SG president in April of 1969. Fellow SG members described him in a memoriam published by The Daily Reveille in 1970 as “a benevolent dictator.”

“He constantly thought about our problems,” former SG member Thomas L. Barnard said in the memo. “[Our problems] kept him awake. The last time I saw him he hadn’t slept for two days.”

During his 10-month term as SG president, Ensminger facilitated a 2,000-person Vietnam War protest on the LSU Parade Ground in October of 1969 and established a department of student rights.

However, Ensminger’s magnum opus while SG president is a program that still exists nearly 50 years after its inception — THE PHONE.

THE PHONE is a 24-hour chat line inaugurated for students experiencing a crisis to call. Since 1970, all University students have paid a $2 semester fee to support the operation of the chat line.

Ensminger did not live to see the program initiated.

In an article published in The Daily Reveille in February of 1970, a staffer wrote, “It is indeed ironic that one of Art Esminger’s pet projects here at LSU was the establishment of a 24-hour telephone number, which any student could call when he or she strung out and needed a kind word or helping hand. His death will certainly spur us on to achievement of that goal.”

Around 4 p.m. on Feb. 11, 1970, SG press secretary Trudy Berger and law school senior Tony Morrison went to the apartment of Ensminger for a wellness check. Ensminger had missed an SG and Board of Directors meeting on Wednesday.

After Berger and Morrison were unsuccessful in entering the apartment, they contacted University police.

On the floor, police found the remains of a male who had died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head. Alongside the body was a 32-caliber pistol.

Friends of Ensminger were able to confirm the body was indeed Ensminger by his “dental peculiarities.” For investigators, the Mickey Mouse wristwatch, which Ensminger frequently wore, was used to identify the body.

On Feb. 19, 1970, THE PHONE was officially sponsored by SG, religious counselors, the LSU Student Union and other service-oriented organizations and was operated by University students. SG was the first organization to donate — pledging $500 for THE PHONE.

Several weeks following THE PHONE’s inauguration, student organizations scrambled to make donations to the program, which only needed $1,200 to begin. Prior to his death, Ensminger pledged $100 of his own money to sponsor THE PHONE. Within two weeks, SG accrued over $1,400 in donations.

THE PHONE’s magnitude led to the inception of the Crisis Intervention Center on campus in 1974, according to the Crisis Intervention Center website. The Crisis Intervention Center is presently known as the Baton Rouge Crisis Intervention Center and now services both University students and the Baton Rouge area.

Assistant Dean and Assistant Director of Student Advocacy and Accountability Tracy Blanchard is a graduate of the University and has volunteered with the Crisis Intervention Center in the past. She said she has worked at the University for 10 years and describes herself as a “connector,” as she connects students to mental health resources or resources outside of the University.

She is also responsible for working with families of deceased students.

“I work with students in crisis and distress — students who have a problem but don’t know who to go to,” Blanchard said.

The University provides food and on-campus housing for the parents of deceased students, so they may be close during the investigation of the student’s death, Blanchard said.

When a student death occurs, parents are often strapped with the responsibility of planning and financing a funeral, Blanchard said. “At LSU, we want to take that burden off of [parents].”

Blanchard said in the event of a student’s death, the first step is to contact the family. The University then shuts down a student’s “89-number” to eliminate the risk of fraud. Then, a notification is sent out to faculty and staff informing them about the student’s death.

The University notifies the roommates, partners and friends of the student. The student’s refund check is then given to the parents, and all existing debt owed by the student to the University is expunged to honor that student.

In memoriam of a deceased student, the University flies an LSU Flag beneath the U.S. flag and the state flag on the LSU Parade Ground. After the flag is flown, it is encased and given to the student’s parents.

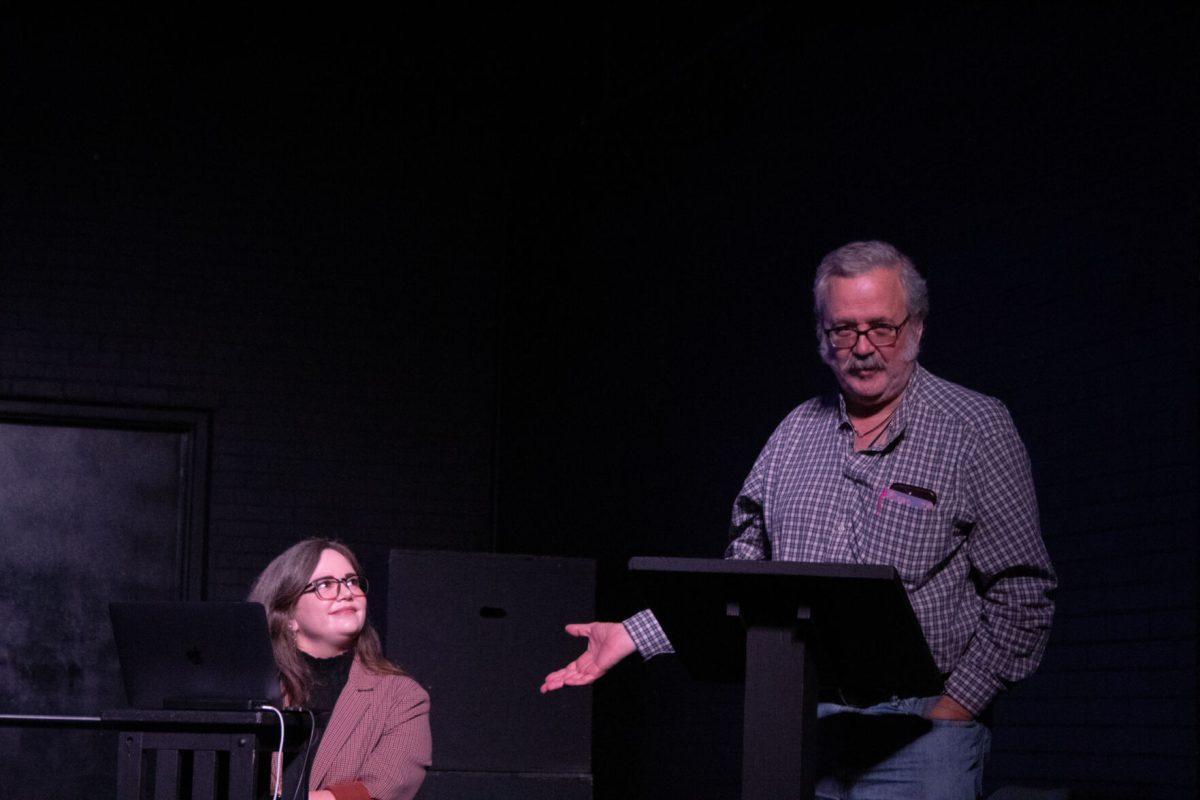

“I don’t want to go to any more student funerals,” Blanchard said, gesturing to two folded memorial flags sitting on her desk — one to be mailed to the parents of Maxwell Gruver, a University student who died on Sept. 14, and the other to the parents of Nickelotte.

LSU Cares is a program organized to help promote the well being of students on campus by providing a range of services like academic or behavioral intervention, a response to grievances and sexual misconduct.

According to a 2010 report by The Daily Reveille, on the morning of March 15, 2010, astronomy graduate student Sarvnipun Chawla leapt from the Life Sciences Building in what the East Baton Rouge Parish Police Department quickly ruled as a suicide.

Blanchard, a member of the University’s C.A.R.E. (Communicate, Assess, Refer, Educate) team, counseled a student who had witnessed Chawla’s suicide.

In response to Nickelotte’s suicide, Blanchard said students should be willing to report a student of concern to the C.A.R.E. team.

“Anytime a student doesn’t graduate, anytime a student feels alone and doesn’t seek our services, and struggles, and suffers alone … I see it as a huge loss,” Blanchard said. “We all just need to learn to take care of each other.”

Blanchard said any type of behavior can be prevented if the University knows early enough.

“I’ve worked with enough people who have tried to commit suicide, or were on the brink of committing suicide — that we were able to know and recognize the signs and intervene, and get that person to the help that they needed before something bad were to happen,” she said.

She said the resources to help students who are suffering exist, but the only problem is making sure students are familiar with these resources.

“We have a very large campus, so it’s hard for students to know where to get services, or they might assume we’ll be too busy,” Blanchard said.

During midterm exams, Blanchard visited several general course classrooms in hopes of letting University freshman know that counseling resources exist.

“Suicide is preventable,” Blanchard said. “Is it preventable 100 percent of the time? I would love to say ‘yes.’”