Scientists have reorganized evolution for all major lineages of perching birds. Perching birds, also known as passerines, are a large and diverse group of more than 6,000 species— including familiar birds like cardinals, warblers, jays and sparrows.

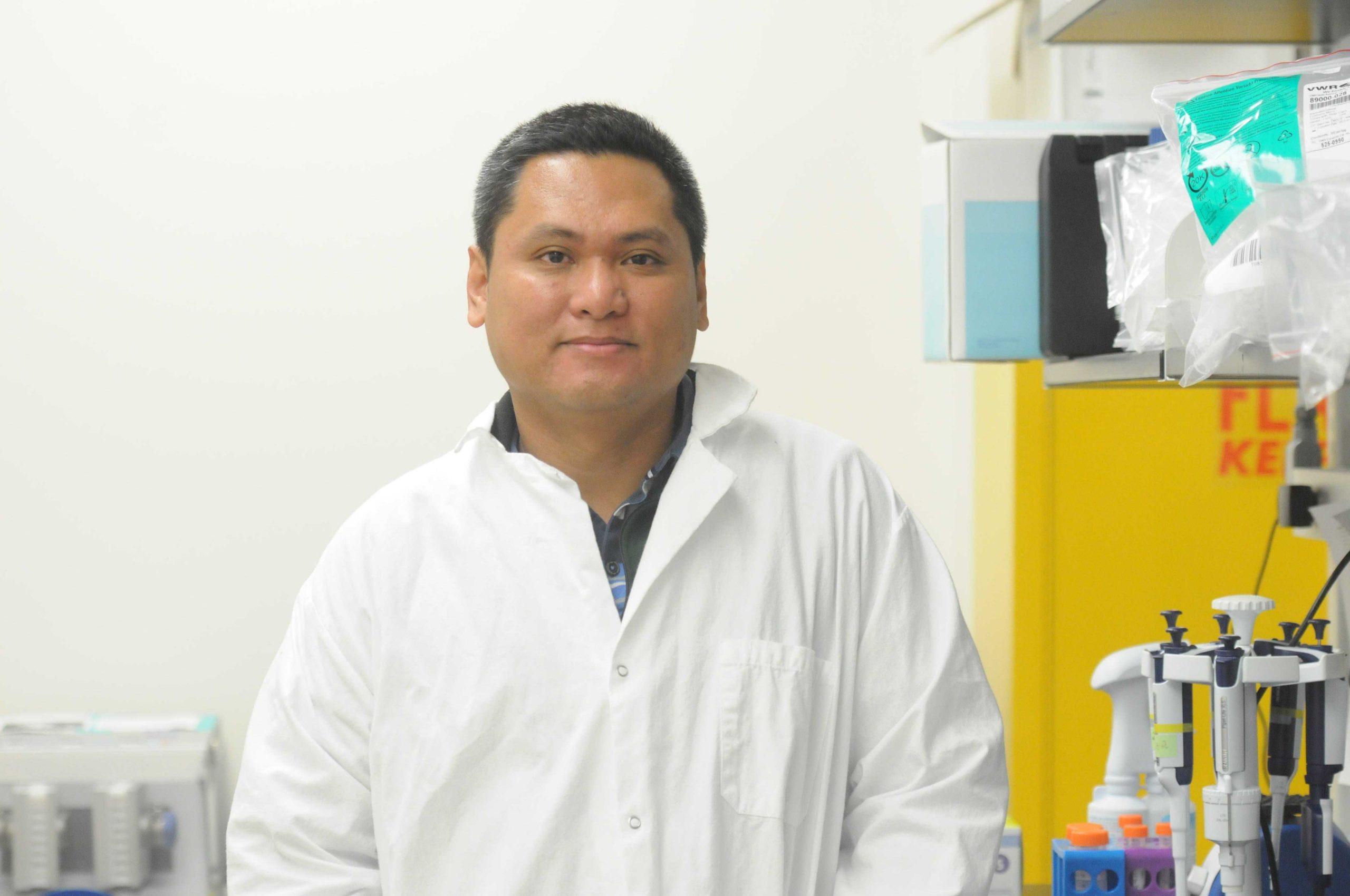

The lead author in this research is postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Biological Sciences Carl Oliveros. Generally, Oliveros tries to reconstruct the evolutionary series in all bird species with genomic data. He uses an evolutionary tree to refer to geography and look at bird migration.

For this study, Oliveros and his team used data about perching birds that has not ever been accounted for and even sequenced DNA from an extinct family from a museum specimen.

Oliveros and his team also looked at how passerines diversified into different species and how that diversification relates to global temperatures. Previous studies said there was a negative correlation but, with this new data, Oliveros and his team did not find a correlation. In their study, they also saw that when passerines go to new land masses they do not diversify like other bird species.

Oliveros and his team found a new family of passerine birds found only in Africa. No one could figure out exactly where these two species they fit into the tree but, with genomic data, Oliveros and his team could. The two passerines are the green hylia and the tit hylia.

Oliveros and his team also found molecular evidence for five more families that were in other studies. This brings the total number of passerine families to 143.

“My favorite part [about this research] is the comprehensiveness of the data and using big data,” Oliveros said. “I was challenged by using such a big data set. It was fun dealing with all this data.”

Oliveros said he thinks their research of inferring evolutionary relationships and its technique will help everyday people. One example Oliveros gave was viruses. People use the same techniques to look at everyday viruses when seeing where and how they spread. Oliveros also believes birdwatchers would be interested in his research.

Oliveros said he once volunteered in a research project where he surveyed whales. Sometimes, the sea would be choppy and they could not go out on the water. Fellow volunteers got Oliverso into bird watching. Oliveros and the other volunteers were later given a grant to survey a remote area in the Philippines, where they discovered a flightless bird species.

Through that project, Oliveros met some professors at the University of Kansas who wanted to do more surveys in that area. Oliveros helped them put together a trip, and they encouraged him to apply to graduate school. Oliveros became interested in evolutionary biology through these surveys and got his masters and doctorate degree in ecology and evolutionary biology from University of Kansas.

LSU researcher reorganizes perching bird lineage

April 9, 2019

LSU professor Carl Oliveros studies the family tree of birds on Friday, April 5, 2019, in the Life Sciences building.

More to Discover