Artist Katrina Andry paints a sobering picture of the dehumanization of African-Americans throughout history in her exhibit “The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came.”

The exhibit, on display at the LSU Museum of Art until March 25, comments on the torment surrounding the Middle Passage, the event in which African slaves were brought to the Americas at the hands of the Europeans. Those who were sick, dying or even newborn were cast over the side of the ships into the water, resulting in inhumane and ridiculing deaths.

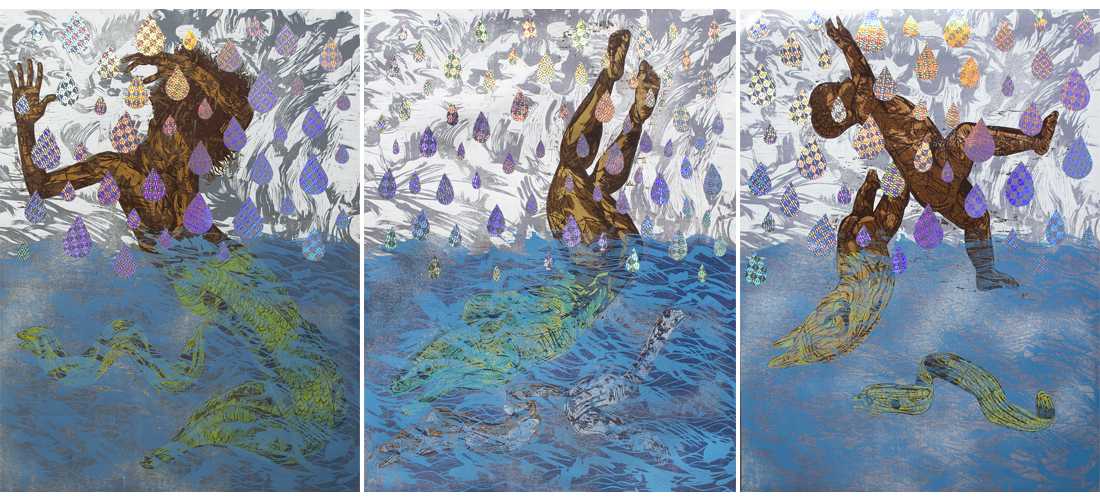

For Andry, events of great prejudice and persecution for black people are held in front of a kaleidoscopic lens, incorporating creative elements to bring these moments in a new light. With “Rainbow” and her partner series “Depose and Dispose (of),” Andry depicts black people as fantastical half-human, half-animal figures — a sobering callback to prejudice and racial slurs.

“The inspiration for the exhibit, I did another series called ‘Depose and Dispose (of),’ it’s another anthropomorphic series of black people as animal racial slurs, so bull, raccoon, gorilla, barracuda, stallion,” Andry said. “That was to reflect how when there’s a loss of personhood, how that can affect someone’s humanity or the lack of humanity being perpetuated onto them.”

It is similar that the figures in “Rainbow,” contorted as they fall into the water below, seem almost mythical as they appear to be mixtures of human and eel. To Andry, this is another analogy to the social hardships African-Americans have faced both in the past and into the modern era.

“I chose them turning into eels because eels in Western society, they’re not creatures we would consider beautiful… they’re creatures that might electrify us,” Andry said. “They’re ugly. They look like snakes with teeth.”

She elaborated on how the symbolism of the eel creates a critique on the scorning of racial difference.

“We have disdain for them, and I wanted it to be a sea creature where we have this disdain for them in Western society that also gets perpetuated against black people, so that’s why they were turning into eels and not like a seahorse or a beautiful tropical fish,” Andry said.

In addition to the multiple pieces featuring emotionally distressed figures in a state of animalism, the series is linked together by the promise of the “rainbow,” appearing as multi-colored raindrops on each piece and an allusion to the biblical tale of Noah and the Ark.

“So the rainbow for me, and playing off of the story of Noah and the Ark… there was this large destruction, almost mass extinction, and then the rainbow signifying that God would never destroy the world in that manner again,” Andry said.

She continued to bridge the story of Noah to the African-American belief in equality, even to this day.

“I’m using that same analogy on how that reflects on black people’s history with contact with Europeans,” Andry said. “So being destroyed, their bodies being destroyed by water or just their lives being destroyed by being enslaved… and then after the [Emancipation], this sort of promise for people to be equal, for people to be realized as fully human instead of being recognized as subhuman or with animal-like qualities, and the promise of that never being fulfilled.”

And although Andry’s work is a reflection on an event that occurred many years ago in a setting far removed from what society knows, the series allows the viewer to ponder if the general message could apply to a world where racial tension continues to rise and a sense of humanity is all but lost.

“This series is something about the past, but it’s meant to link about the present with the ‘Depose and Dispose (of)’ series, so for sure it’s commentary on when people are treated as if they’re not being fully recognized as human beings, there’s societal consequences to that,” Andry said.

To a viewer of the exhibit, one could even pose this question — Will the promise of the rainbow ever come? Will the waters which damaged the face of an oppressed people throughout history start to recede? Andry is doused in skepticism.

“I don’t know… I don’t want to be really pessimistic but I also think, too, that when you have a group of people that have historically been advantaged and in power, no one wants to give up power,” Andry said. “People tend to feel like if all things are equal, then some things are going to be taken away from them, when in reality, it’s just all things will be equal.”

On her circuit of revealing a scourged face to the masses regarding African-American prejudice, Andry hopes that there will come a day that the rainbow does cast its light.

“I think that another radical movement might have to happen where we might be able to make our own community that can support each other,” Andry said. “That is less reliant on needing someone else to justify our means.”