LSU’s Undergraduate Society for the Study of Religion welcomed Harvard University’s Dr. Steve Jenkins for his Compassion and Terrorism: A Buddhist View lecture on Tuesday.

Religious Studies Associate Professor Paula Aria said Jenkins’ talk, which discussed Buddhist beliefs on violence, was relevant in the midst of several on-campus active shooter scares, including the Coates Hall armed intruder scare on Aug. 20.

“Just recently, we had the active shooter scare in Coates Hall. I was probably not alone in thinking ‘what am I going to do?’” Aria said. ”We decided this topic was very timely.”

Jenkins began the conversation by stating Buddhism has never been an inherently pacifist belief system. The idea of Buddhism as a pacifist religion is a romanticized and overly exaggerated notion, stemming from those unfamiliar with East Asian culture.

“We are engaging in fantasies of who we want Buddhists to be,” Jenkins said.

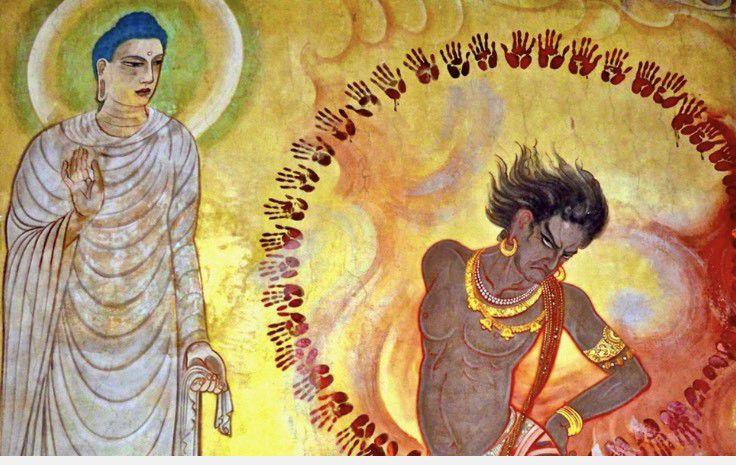

The Western world also mistakenly credits Buddhism with not forcing conversions, which contrasts from the often violent conversion habits of some Western religions. However, Jenkins said Buddhists have historically implemented the death penalty and engaged in warfare. The Buddha himself said that, in a past life, he had killed Brahmans and “sent them straight to hell.” In other past lives, the Buddha has been a war horse and a war elephant.

Other famous Buddhist kings sentenced thousands to death for disrespecting sacred religious images. According to Jenkins, there is an understanding among Buddhists that killing an enemy of the Dharma is no more harmful than killing an ant. However, as the Buddha once said, “one who goes to battle with the intention to kill is going to hell.”

Intention is crucial and so is the difference between harm and violence, according to Jenkins.

Additionally, the social status and relationship with someone a person kills matters. If someone killed their own mother, they would instantly go to hell, according to Buddhist beliefs. However, killing someone else’s mother isn’t an unforgivable sin but could affect one’s karma depending on their intentions. Jenkins also said karma can be gained by killing people with good intentions.

The current Dalai Lama is revered for his peaceful nature, but Jenkins said he is not representative of the entire Buddhist thought process any more than Gandhi is representative of all Hindu people.

When the Dalai Lama originally heard about the war in Iraq, he said he “wasn’t sure if it was good or not,” proving the Dalai Lama finds war acceptable and even necessary under some circumstances. Upon hearing about Osama Bin Laden’s death, the Dalai Lama initially approved. However, he revoked his blessing when he learned it was an unarmed assassination, rather than a war killing.

“Violence is a clunky English term,” Jenkins said. “We have to understand what the word violence really means.”

At Harvard in 2009, the Dalai Lama explained there is “violence on a physical level” that is “essentially non-violent.” This might sound like a non-sequitur, but it allows for compassionate and self-defense killings, which are neither violent nor immoral.

Jenkins said early Buddhist legends state people used to have philosophical debates rather than physical altercations.

“Imagine if instead of playing Florida this weekend, the debate teams of both schools had to debate, and the entire endowment of the school depended on it,” Jenkins said.

Punishments for losing philosophical debate could involve removal from the Buddhist Monkhood.

Although misconceptions about Buddhism can largely be attributed to twisted Western imaginations, Jenkins said Buddhist leaders also overemphasized their peaceful sentiments in order to gain public support.