Despite its reputation as a party drug for rich teenagers and Burning Man attendees, MDMA may soon find its way to your therapist’s office, and for good reason.

MDMA, more popularly known as ecstasy or molly, is a hallucinogenic drug that creates heightened sensations, empathetic responses and euphoria.

It once enjoyed legal status, but it was banned in 1985 due to fears that it would turn the brains of America’s youth to mush. Although this fear has little basis in truth, MDMA can damage neuron endings, cause hyperthermia and, like any drug, be fatal if taken in too high a dose. Despite these side effects, psychologists across the globe have been giving MDMA to patients with PTSD in experimental therapy sessions since the 1970s.

In the thousands of sessions that have been conducted, the results have been encouraging. MDMA allows patients to temporarily relieve themselves of their usual anxieties and openly communicate with their therapists, which allows therapists to pinpoint what exactly is bothering patients.

Their usual painful emotional responses to trauma are suppressed while under the drug’s influence, allowing for substantial self-reflection and healing.

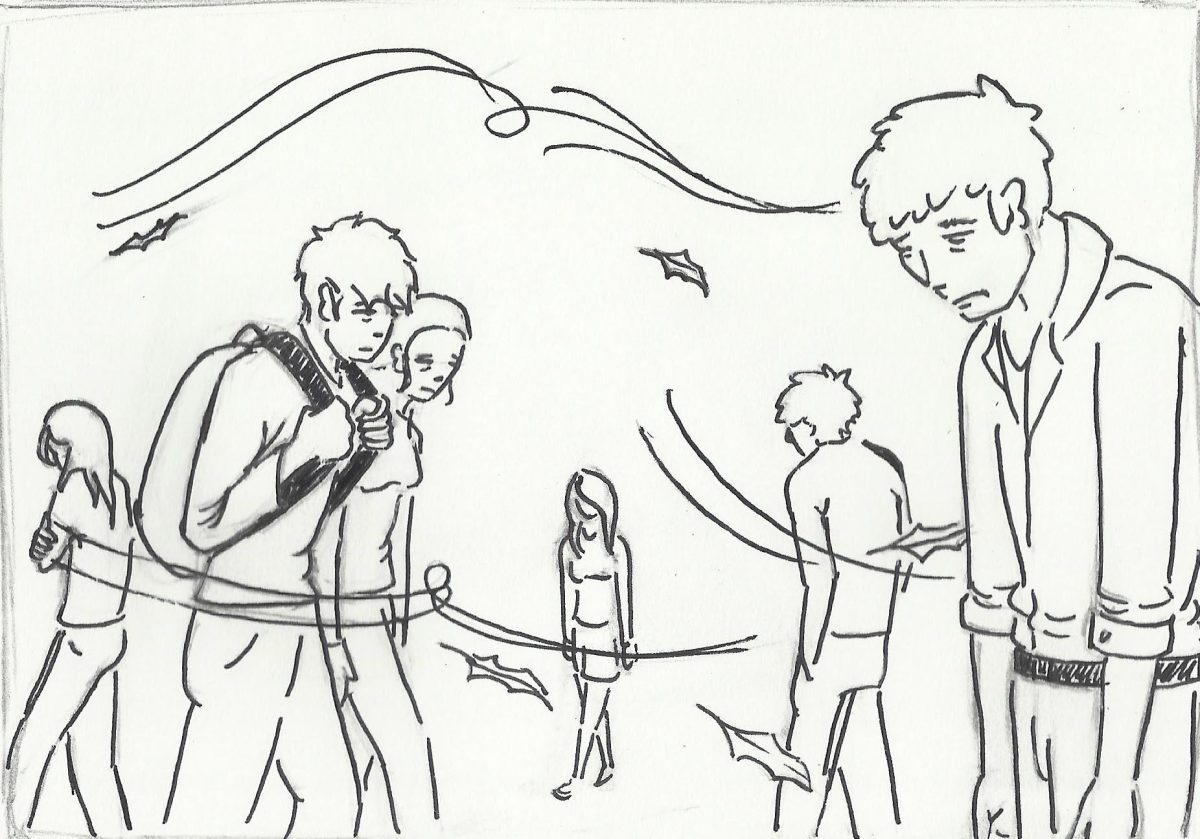

Group therapy is even further enhanced because of MDMA; with the introduction of the drug, bickering couples and estranged families can temporarily put aside differences and address each other with the love they once shared.

Given the reputation MDMA has always held as “the love drug,” it is not surprising that it would be so effective in helping people get past personal trauma and injury.

What is surprising, however, is how unwilling government agencies have been to entertain the possibility of legalizing the drug for medical use.

Some optimistic reports place the beginning stages of legalization as just a couple years away, but others are more pessimistic due to several major roadblocks that still stand in the way of MDMA’s full legalization for therapeutic purposes.

The first of these roadblocks is that recreational MDMA use has, on rare occasions, resulted in deaths from unforeseen reactions to the drug. However, most of these deaths are not due to MDMA itself, but to the other drugs frequently addedto street MDMA pills, which range from caffeine to methamphetamine. The MDMA pills therapists use are pure, thus posing much less risk, if any risk at all, to patients.

The other major roadblock to MDMA’s partial legalization is the depression many users report when coming down from the drug’s effects. Since MDMA works by accelerating the rate at which neurons absorb serotonin, the chemical that makes us happy, the body finds itself depleted of its usual serotonin reserves once the drug wears off.

Opponents of legalizing MDMA argue that this post-MDMA depression cancels out the benefits of using MDMA during therapy, since patients may leave sadder than they were when they began. However, many patients actually report feeling peaceful once the MDMA wears off after therapy, suggesting the depression reported by recreational users may be tied to high-dose, long-term use and the high-energy environments associated with MDMA use.

With the indisputable potential MDMA holds as a key to releasing millions of Americans from the prison of PTSD, it seems ridiculous that the federal government hasn’t legalized its medical use yet.

Instead of blindly following the disproven myths and fabricated propaganda surrounding hallucinogenics like MDMA, federal bodies like the DEA need to listen to the science. Countless Americans are a pill and a therapy sessionaway from healing, with only a piece of legislation standing between them and a trauma-free existence.

Cécile Girard is a 19-year-old biology and psychology major from Lake Charles, Louisiana.

Opinion: MDMA beneficial for PTSD sufferers, should be made legal for medical use

September 3, 2019

MDMA Cartoon