It was not by my own efforts that I missed first-year orientation at the University two years ago. Mostly, I was not interested in being paraded around campus for hours just to be told that Middleton Library, which stays open 24 hours during the week, would be torn down and replaced by a library that I would never be able to use. Or the LSU Bookstore located beside the Student Union would rent me the exorbitantly-priced textbooks that I would need for my new classes each semester. However, my phone had actually failed to remind me that orientation started on the 16th of August and not the 17th.

In hindsight, missing orientation was not an experience worth regretting because whatever belief of the University being a secure place that the polo and khaki-short clad orientation leaders could have conjured in me would have been quickly squashed within a month of being here.

Between leading hordes of freshmen down Free Speech Plaza and handing out glossy purple and gold pamphlets with bulleted lists on time management and study skills, orientation leaders would not have been wrong to mention the barrage of death and violence that students would encounter or hear about within the first few weeks of being on campus.

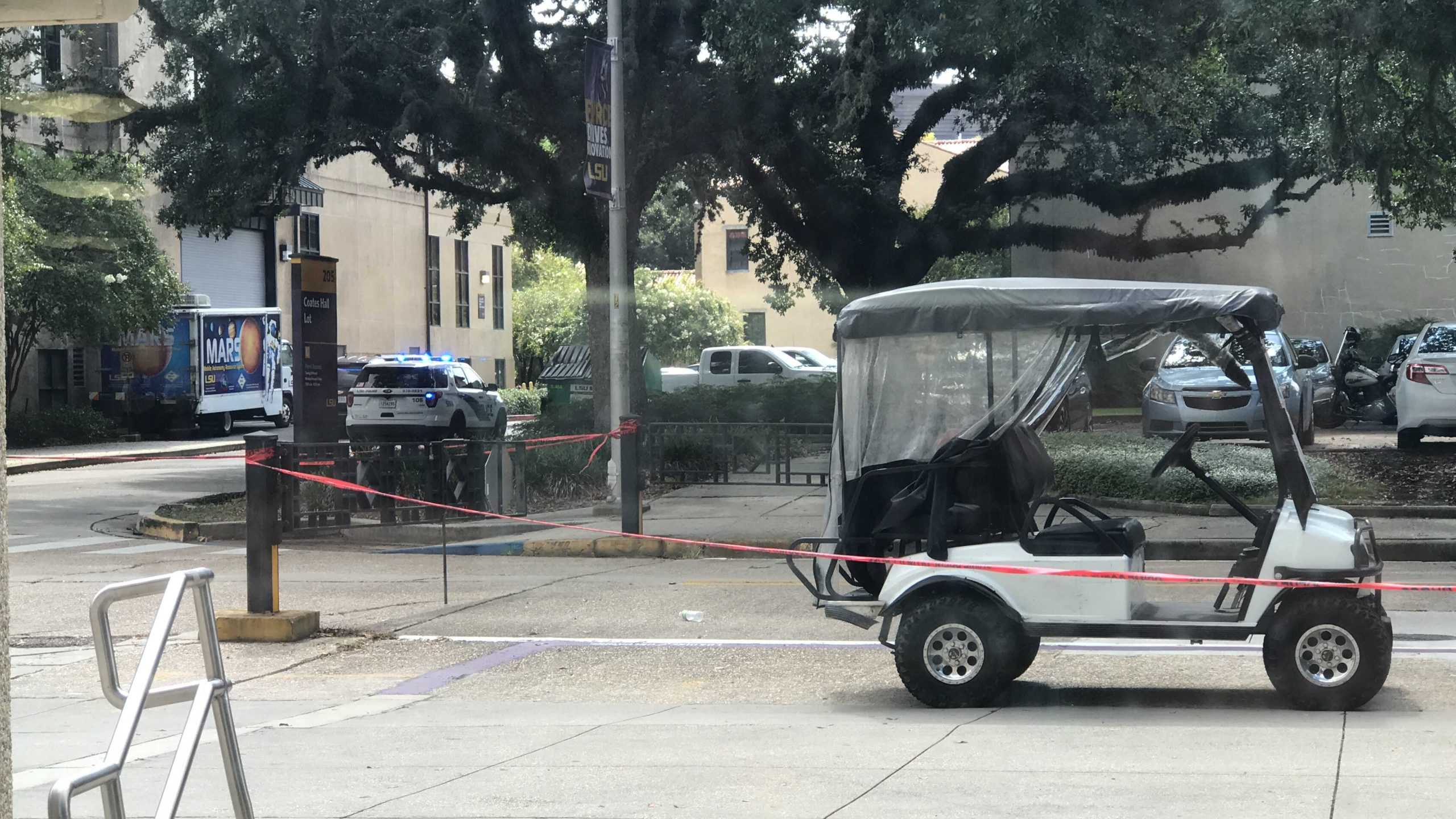

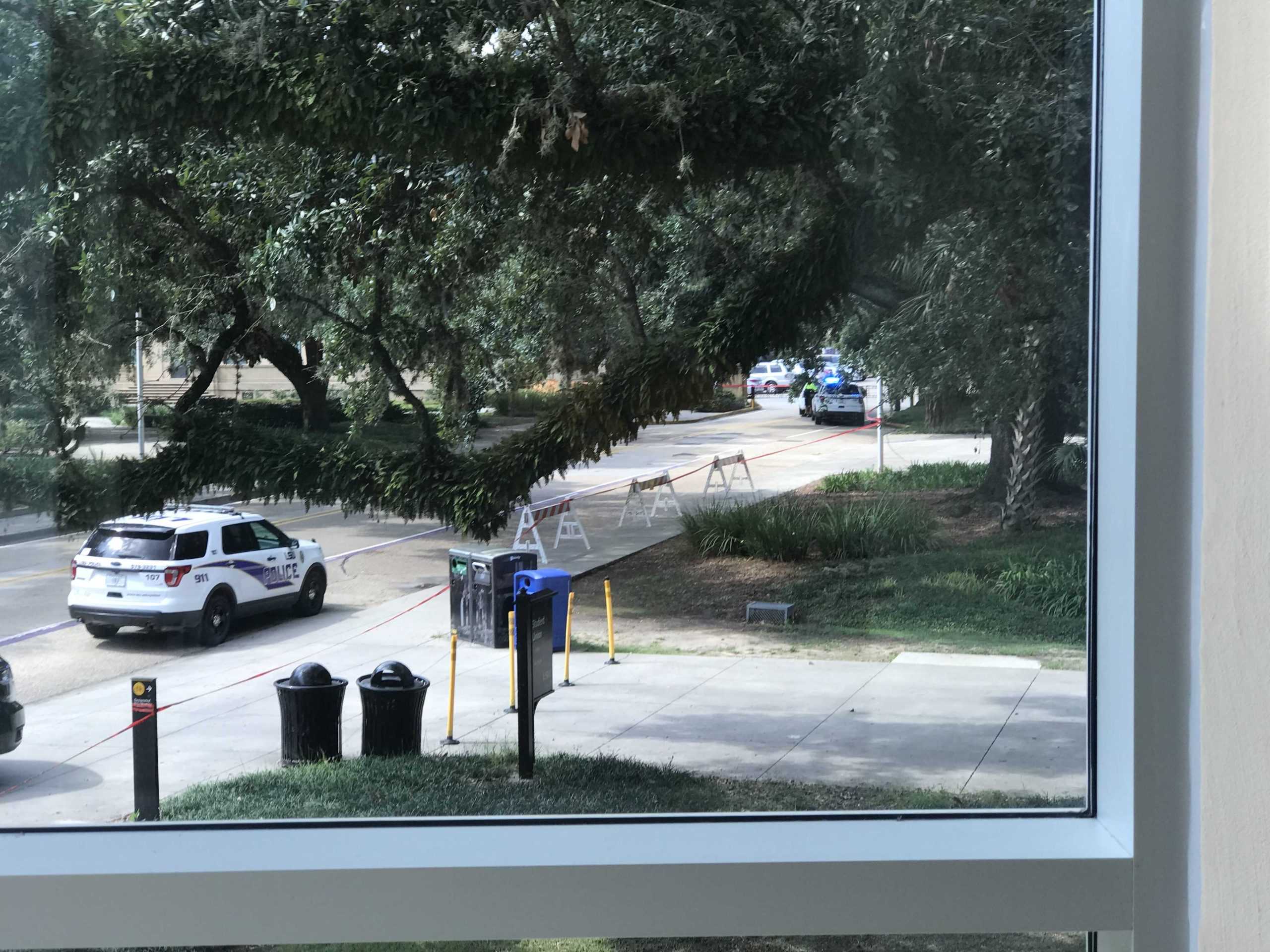

This year, that encounter with violence—which turned out to be “harmless”—involved a plainclothes, yet armed, law enforcement officer casually ambling Coates Hall.

Roughly a year ago, four students were struck by cars while waiting at a cross walk on the intersection of Nicholson Highway and Skip Bertman. Just last month, sophomore Sarah James was struck by a car and killed while crossing the street near Tigerland.

Earlier this year, female students began discussing and reporting their broad-daylight encounters with coercive men—men posted up in grocery store parking lots, ambling campus pathways and hidden in the stalls of restrooms—who were attempting to abduct them.

Moreover, students began discussing the futility of using the glitchy Shield App, the untimeliness of the Tiger Trails bus route and the few and far in between Rape Aggression Defense Classes available on campus.

These discussions on campus safety are necessary and must come from those who are directly impacted by the University’s failure to do things like provide sufficient lighting throughout the campus and establish a convenient and functioning way to report activity on campus that is overtly criminal.

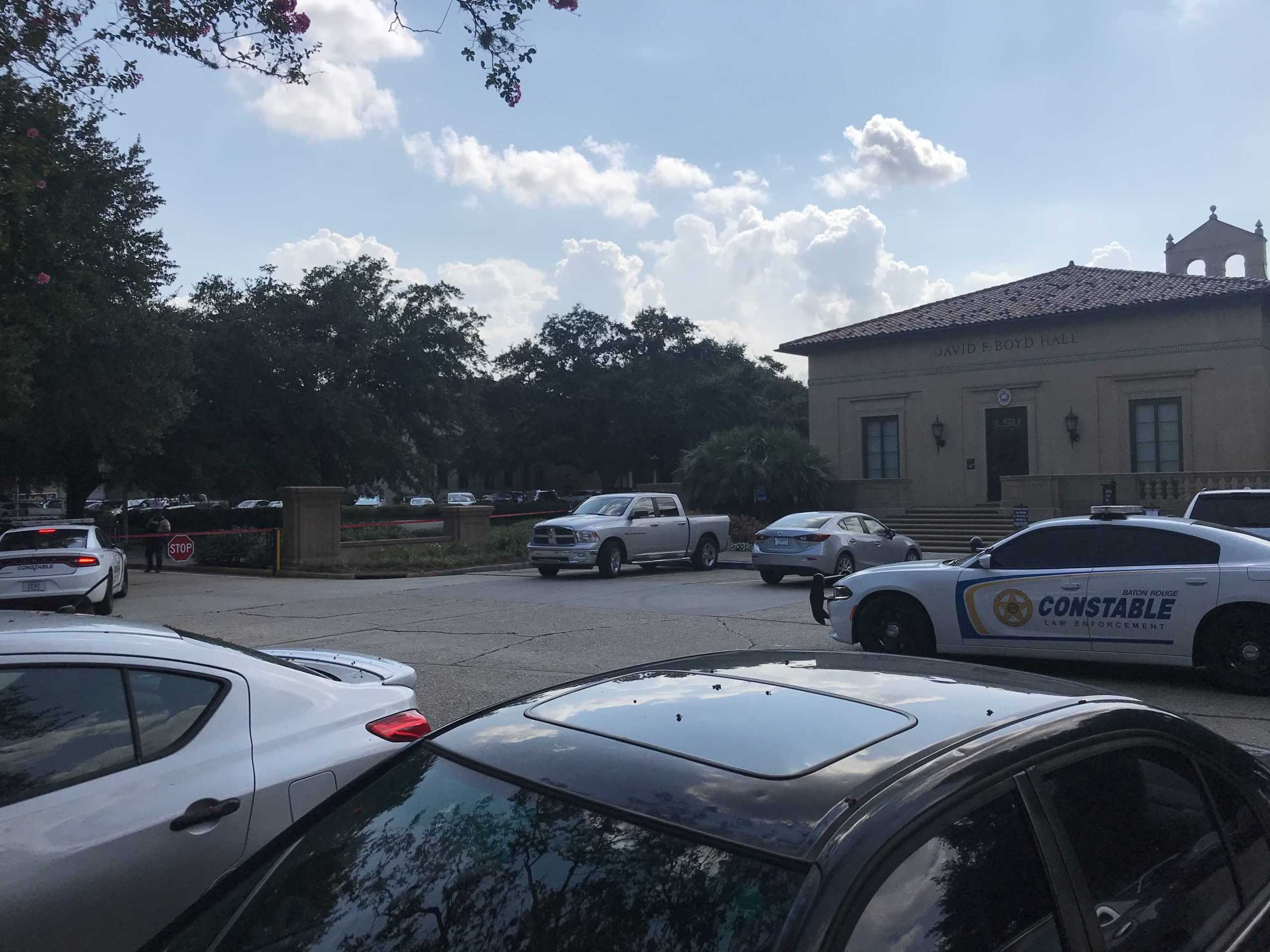

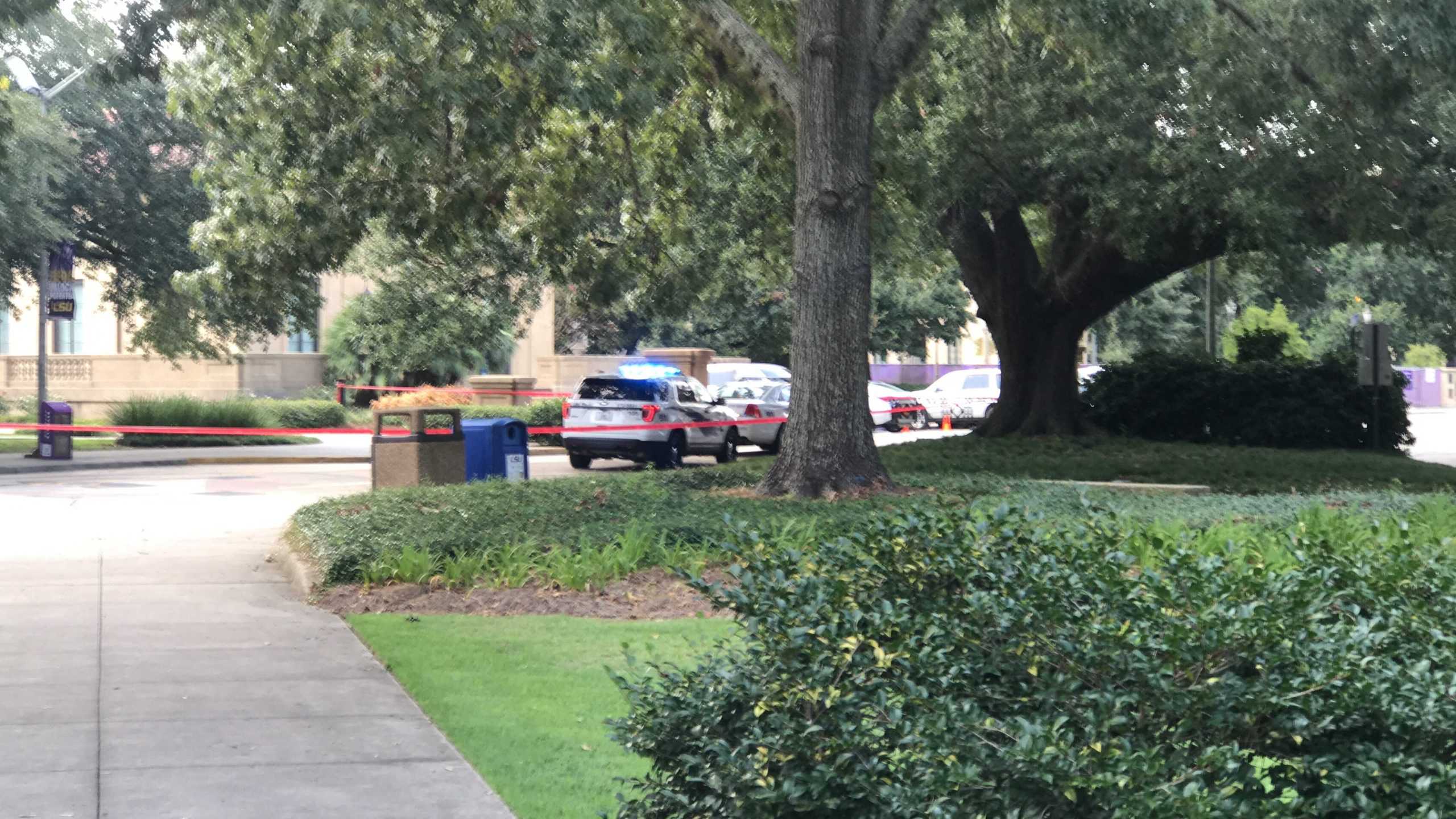

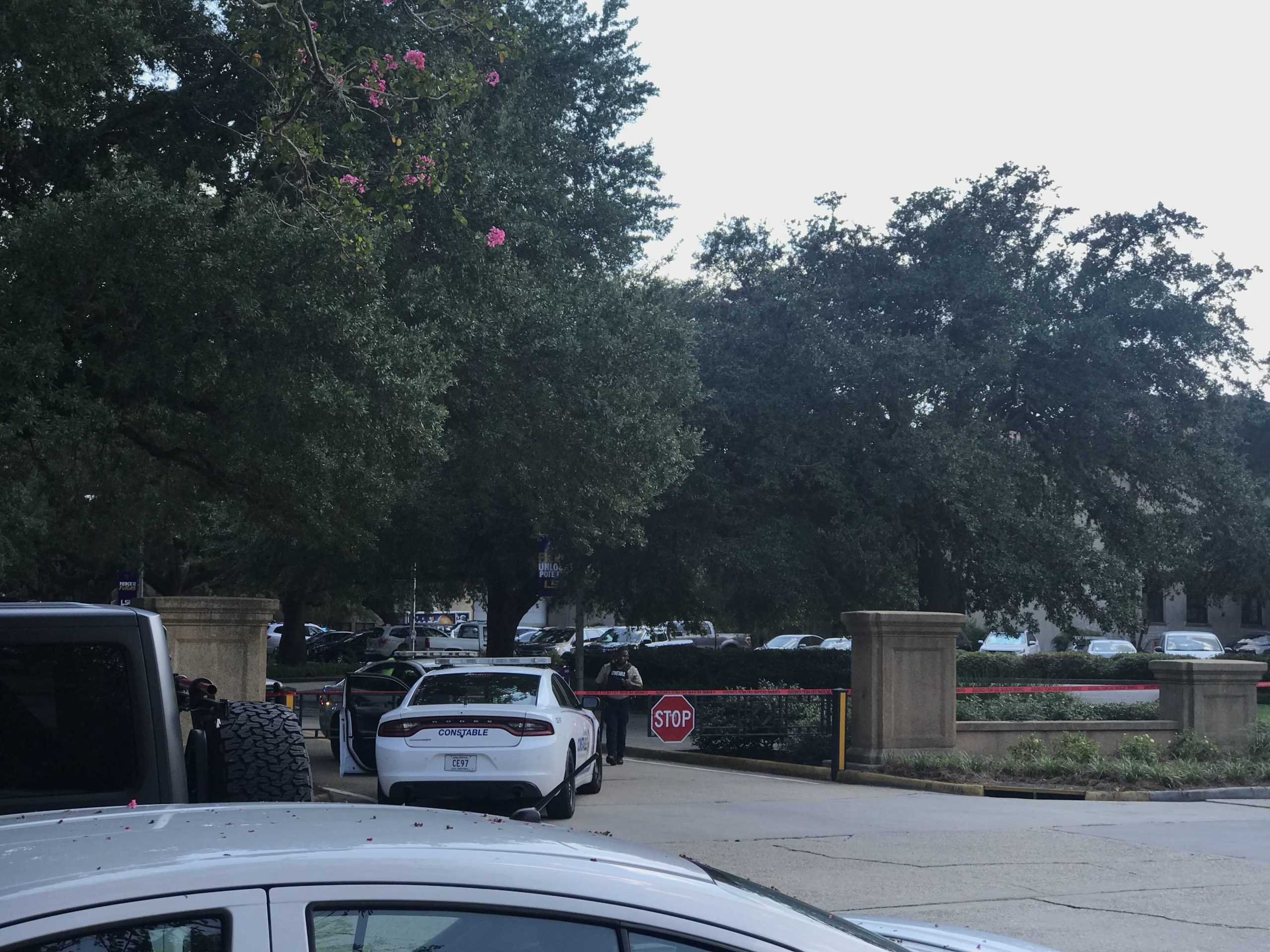

In an article published by The Reveille titled “LSU students concerned, question campus safety amidst suspicious incidents,” reporter Anna Jones interviewed several students who suggested a larger police presence would help prevent crime. An increased visible police presence is not an appropriate response to the violent activity occurring on campus. More police do not prevent crime but contribute to over-policing; a result of which is the incident involving an armed and plainclothes cop being mistaken for an armed intruder this past Tuesday, to which LSUPD suggested students “Run. Hide or Fight.”

Over-policing would only exacerbate the lack of trust between LSUPD and students and does nothing to reestablish confidence in LSUPD’s ability to protect students—made evident by the resoundingly critical response to LSUPD’s suggestion to students, faculty, and staff’s advice to “Run. Hide or Fight.”

LSUPD: Reported armed intruder in Coates Hall. Run, Hide or Fight. LSUPD on scene. Monitor https://t.co/ZpdXns8r3I for further information.

— LSU (@LSU) August 20, 2019

These faulty and harmful alerts are not a first for LSUPD. On Jan. 3, 2015, students received an LSUPD emergency alert for an armed robbery that occurred in the Kirby Smith Hall parking lot. The alert described the suspect as a “black male wearing dark hoodie.” The vague description warranted protest by students of LSUPD for putting black male staff, students and campus amblers in danger of being pursued by the police for simply matching a too vague description. A spokesman for LSUPD, Capt. Cory Lalonde, told The Reveille that the department is “constantly looking for new ways” to improve.

Just two years ago, on Sep. 14. 2017, during my first year as a student at the University, 49-year-old Donald Smart was walking to Louie’s Café near Newk’s Eatery, where he worked as a dishwasher during the night shift. Before Smart could make it to the diner, he was fatally gunned down by Kenneth Gleason, a former LSU student, who just two days prior, had murdered another black man in Baton Rouge.

It is not clear how many times Gleason visited campus in the three days it took the Baton Rouge Police Department to arrest him on drug charges, yet it was clear that LSUPD failed to alert students that the shooting had occurred and that BRPD suspected, but had failed to inform the public, that the shootings had been racially motivated.

Within that same month, the hazing death of freshman Maxwell Gruver occurred, as well as the suicide of senior Michael Nickelotte, who had been missing for over a week before his remains were eventually found in the woods off Nicholson Drive.

Violence and death have been an integral part of my experience at the University. The various incidents that have occurred these past two years make it evident that the University needs to holistically rethink its dedication to student safety.

The University’s medical amnesty policy was a step in the right direction, but it did not make up for the silence of the administration regarding the gender violence, racial violence and domestic violence that has consistently occurred on campus for the last two years needs to be addressed through policy changes and the implementation and better funding of more programs designed to protect students/ mental and physical health as we navigate our campus.

Alden Ceasar is a 21-year-old English senior from Clinton, Louisiana.

An earlier version of this story had misspelled Louie’s Cafe. It has since been corrected.