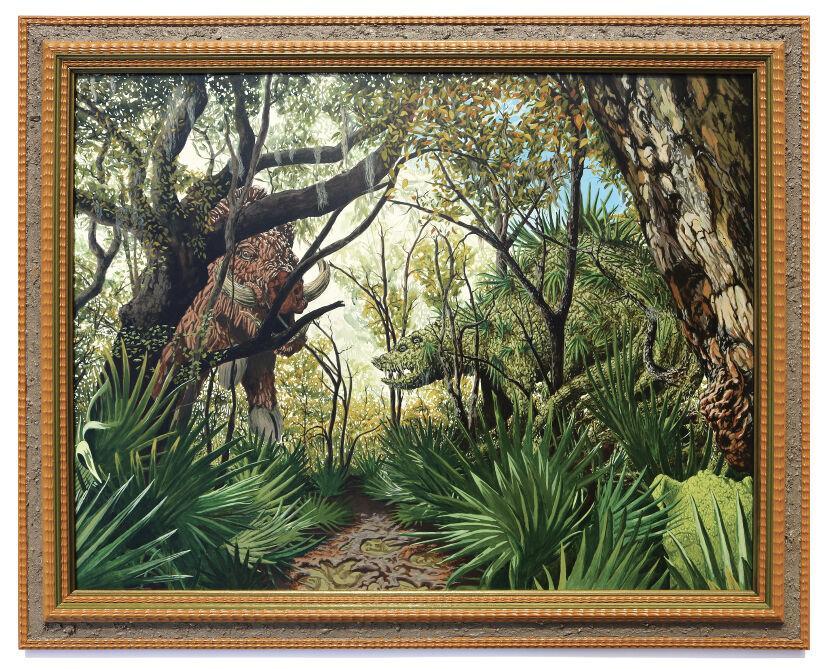

A large, wooded boar shows its tusks to a stegosaurus-like creature with palmetto leaves on its back. The beastly boar destroys the swamp beneath him, while the Palm Guardian battles back.

“In this moment, as the great wooded boar lunges toward the Palm Guardian, one can only hope to see the vindicating strike of père Palmetto’s tail deal a swift death to this plague of destruction,” reads the English translation of the story accompanying the painting.

If you were reading the piece on the author’s website, it would look like this: “En ce moment, lorsque le grand cochon boisé fonce vers le Gardien palmiste, on ne peut que souhaiter oir le coup justifié de la queue à père Latanier qui donne une mort prompte à cette peste de destruction-icitte.”

Jonathan “radbwa faroush” Mayers, a 2007 LSU alumnus, is a visual artist and writer who combines his love of art with his love of language, particularly the endangered Louisiana Creole language Kouri-Vini.

A Baton Rouge native, Mayers learned his ancestors spoke Kouri-Vini, a language that developed in 18th century Louisiana from contact between the French language spoken by colonial settlers and various West African languages spoken by slaves. Fewer than 10,000 individuals speak Kouri-Vini today – Mayers is one of them.

“It’s a language of survival,” he said.

Through the encouragement of family and friends, Mayers took on learning his heritage language.

He became involved with several Kouri-Vini revitalization projects. He provided voice recordings for Google’s endangered language app, Woolaroo. An artist since birth, Mayers combined his newfound passion of language with his art, providing illustrations for “Ti Liv Kréyòl,” a learner’s guide to Kouri-Vini. He also took the initiative to translate the writings on his personal website.

He’s even translated his nickname, or ti-nom, into Kouri-Vini: “Radbwa faroush” means “feral opossum,” a moniker Mayers adopted during his time as a student at LSU. It was born from a conversation with friends, and it’s stuck ever since.

But picking a career path was not as simple as picking out a nickname. Mayers started college as a computer science major before trying graphic design and finally settling on art.

“Going into visual art was, like, very freeing,” Mayers said. “It was cathartic. I could express, you know, any sort of thing that I was thinking.”

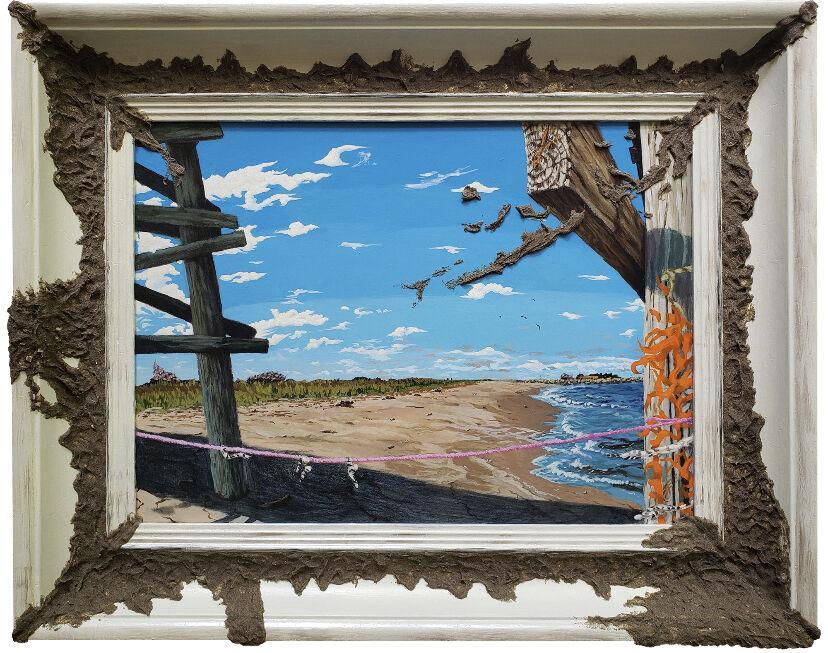

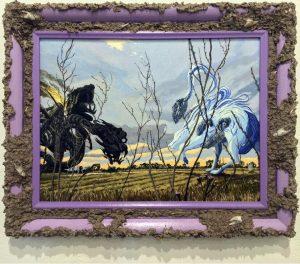

Much of Mayers’ art expresses environmental themes. He paints mythological creatures into southern Louisiana landscapes.

Mayers grew up with a love of the outdoors, fishing and visiting the family camp in Belle River. He said spending that time in the swamp was inspiring and helped him realize just how important the environment is. He believes it’s important to consider all the culture and tradition that is at risk if the environment is lost.

Many of his paintings are accompanied by short narratives, written in Kouri-Vini, that explore human-caused environmental change, like the introduction of habitat-destroying non-native species or the impacts of the oil and gas industry.

“The work is not just the painting,” Mayers said. “The work is the painting and the story, and perhaps how I present it, so then it’s like it can become performance.”

Mayers includes pieces of the physical place in the presentation of his paintings. He incorporates mud, sediment and sand from the locations he is depicting onto the frames of the artwork.

“A sense of place, I think, is important, even if it can be put in sort of a smaller compact thing that you can bring around,” Mayers said. “I don’t get out as much as I would like to, to all these places. Even if I never go back, I will always hold them in high regard—all these places, the people I meet out there—because those are the things that are going to always be important.”

As a cultural activist, Mayers said the overarching goal for his artwork is to elevate the culture and community.

He calls his effort “Latannyèrizm,” and explains it as a style of colloquial visual art that weaves regional language and physical place.

Baton Rouge’s Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome appointed Mayers as Baton Rouge’s poet laureate in the summer of 2021.

“Jonathan’s work inspires others to protect and preserve the historic Creole culture within Louisiana; the combination of both Kouri-Vini and his talents will help keep this language alive for future generations,” Broome told The Advocate. “This unique asset will strengthen the cultural fabric of our community.”

Mayers will be presenting some of his latest poems and reading works in Kouri-Vini at the Baton Rouge Gallery, 1515 Dalrymple Drive, on Sunday, Sept. 26 at 4 p.m.

Mayers said he hopes his work will continue to help put Kouri-Vini at the forefront and build a sense of wonder around the place he calls home.

Mayers said one of the best pieces of advice he ever received was to start making the work you’ll want to see when you look back 50 years from now.

His own advice to current students echoes a similar theme.

“Any of the interests that artists have at LSU, like as students, add that into the work that you’re making,” Mayers said. “Whatever someone’s interested in, bring that into your artwork.”

LSU alumnus combines art with Louisiana Creole language Kouri-Vini: ‘a language of survival’

By Ava Borskey

September 22, 2021

This painting by Jonathan Mayers entitled “Le Grand Cochon boisé contre Le Gardien palmiste (The Great Wooded Boar vs. The Palm Guardian)” includes Jean Lafitte sediment on a repurposed frame.