This is the fifth piece in a series of first-person accounts of how students are dealing with the coronavirus pandemic, written by the Reveille’s opinion columnists.

There’s nothing eerier than looking at videos of an empty Times Square knowing I was there only a little over a month ago. While I was staying in Manhattan, the first case of COVID-19 in New York City was confirmed, and even saying the word “coronavirus” out loud in public was taboo. I’ll never forget the moment on the flight home when a woman loudly described me disinfecting my tray and seat as “ridiculous” and “overreactive.”

The following day, I’d be back at my retail job, interacting with hundreds of customers during my shift. Over the next couple of days, my frustration with people still visiting the mall grew as I followed the increasing amount of cases in NYC. Unbeknownst to me, in the coming weeks my multibillionaire employer would put 80,000 employees on an indefinite furlough, including all of my coworkers and me.

As classes officially moved online, I moved back into my parents’ house. Unfortunately, my loved ones and I don’t have the luxury of running away to a secluded lake house. Instead, I’m still having to avoid direct contact with my dad, who is an essential employee at a chemical plant in Geismar and has to interact with multiple people daily.

My sister, a hairstylist, is also out of work indefinitely and is struggling to get accepted for unemployment as a small business owner. As she stays home to take care of her 8-month-old son and 4-year-old daughter, her husband is having to work all day to provide for them. FaceTime has come in handy as a way to spend time with my niece and nephew, but sometimes Paw Patrol is more important than me.

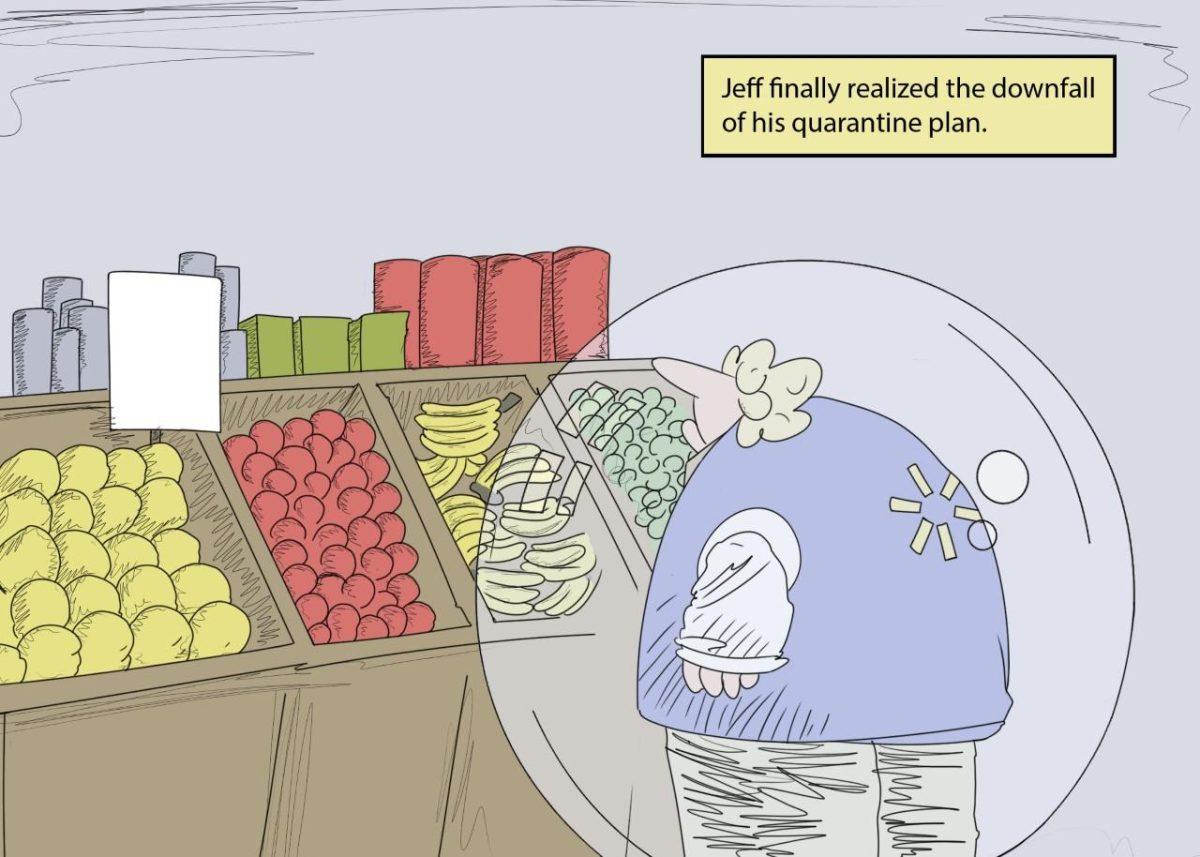

Before this, I spent most of my days at my boyfriend’s house. However, since he’s a manager at a large grocery store chain and an essential employee, we haven’t seen each other face to face in a month. We talk every day about how it’s inevitable that he’ll be infected, and even though I try to convince him to quit or just stay home, rent is still due at the first of every month.

These experiences have made me realize what a luxury it is to be able to consciously make the decision to social distance. The idea of being able to carelessly watch Netflix all day and complain about it online baffles me. Meanwhile, the people still required to work with the public are risking their health daily in order to keep up their income and support their families.

It makes you question how disproportionately this virus is affecting the lower working class. Though my middle class family is suffering, it’s much worse for the people with low-wage jobs and little-to-no healthcare. It’s a privilege to be able to stay at home without worrying about finances, and more people should be thankful that their only gripe is with being bored.

Gabrielle Martinez is a 19-year-old mass communication freshman from Gonzales, Louisiana.