Stars: 5/5

An institutionally enforced addiction to tranquilizers in the formative years of youth and unknowable inherited traits from an unstable mother are an unlikely breeding ground for unadulterated genius. Nonetheless, Elizabeth Harmon (Anya Taylor-Joy) found obsession, glory and purpose in the grand old game of chess from the young age of nine, where it would remain the centerpiece of her existence for a huge part of her life. “The Queen’s Gambit” shares enthrallment through concise storytelling, leaning into Beth’s quiet nature by allowing actions and attention to direct the audience’s information gathering.

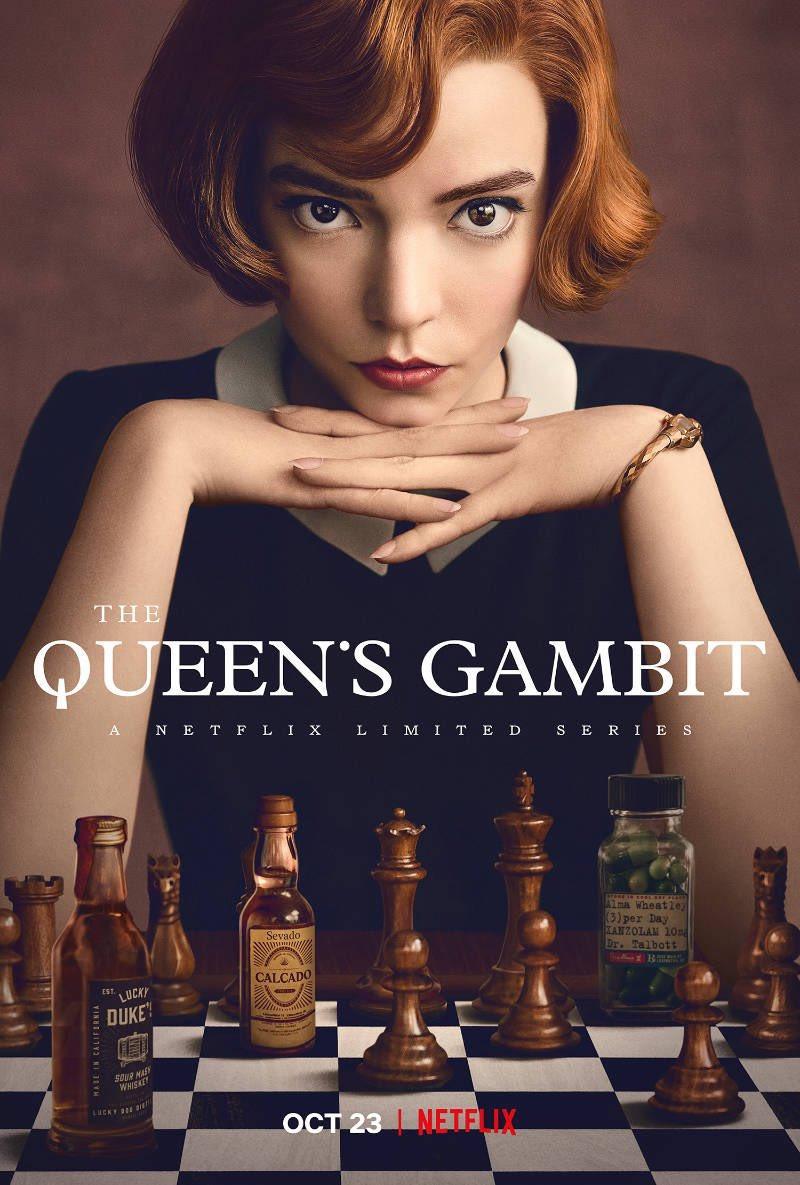

The series of wildly unfortunate events leading up to Beth’s childhood at Methuen are extensively damaging, some brought on by personal circumstance and others by the nature of being an orphan in the 1960s. Mental health was branded as taboo and disregarded on a societal scale due to severe misunderstanding and lack of research. As a result, legislation to legally administer sedatives to impressionable wards of the state raised no red flags until mass withdrawal was unavoidable, at which point they were banned. This fosters a lifelong practice and unhealthy dynamic involving chess analysis/simulation and inducing a substance-assisted mental haze of calm. It sows the seeds for Beth’s intense alcoholism and general tendency to dissociate for an “edge” in chess.

Beth’s adopted mother Alma Wheatley (Marielle Heller) contributes some of the best prose in the series from her melancholy cage of housewifehood in bland suburbia. The soft and rarely spoken “tweenage” girl she finds briefly flickers a hint of purpose into her life before Mr. Wheatley, an archetypical emotionally unavailable male figure of the ‘70s, stamps it out. She is my favorite character by far on account of her positive role in Beth’s life and her proclivity to craft and deliver beautiful sentences throughout the film.

Though brilliantly intelligent and analytical from the start, Beth didn’t exhibit the vibrant personality she grows into until facing adversity in the chess scene. She played it cool and confidently as a strategically-gifted cucumber at the chessboard and was equally calculating in her personal life, except for a few cute exchanges between her and childhood best friend Jolene (Moses Ingram). Losing a match to Benny Watts (Thomas Brodie-Sangster) appears to derail the emotionless march toward excellence Beth anticipated. This event in episode three marks a substantial tone and behavior shift worth exploring as she grapples with her first real shortcoming. The ensuing rivalry between Beth and Benny elicits one of the most cinematic sequences commercially available which single-handedly validates the entire mini-series.

If audiences didn’t understand her soulless inquisition as a child and teen, the character trajectory implied by her new self-doubt and coping method ensures interest. The friendships (and more) she makes during this period grant major insight into her perceived social norms and interpersonal relationships. Themes of the cost tolled by her innate brilliance variably manifest here in showing her struggle to connect with the vast majority of people she encounters. Chess and substances are too pervasive in her life to nurture “normal” relationships, though their prominence waxes and wanes with her mental state. Only people in the chess world, her family or a lifelong friend may find the sharp-witted and genuinely curious-minded side to Beth Harmon. All others may expect one-word answers and overwhelming indifference.

Especially in the realm of sports and competition, absolute devotion and nothing less earns the grandest titles. Chess is not the most broadly appealing pastime available, either. Every character makes their opinion and knowledge regarding chess known in some form, and that directly correlates to Beth’s perception of them. The flip side of being a prodigy is the inseparability of the talent from the individual. Without chess, Beth is a drifting island of misery that consumes itself when left to stagnate. When she plays, chess consumes her. It is the unilateral focus that occupies most waking thoughts, informs her social network, ambitions and level of contentment. If they do not offer chess help or an avenue into an unexplored aspect of life, Beth will not bat a long, pretty lash at their presence or absence.

Its quantitative critical acclaim speaks for itself, but it bears reiterating: “The Queen’s Gambit” has the intangible quality that constitutes a piece of culture rather than simple media. Though undoubtedly a period piece, it captures a timeless sentiment of the loneliness and cost of greatness. For one aspect of life to prosper so thoroughly, all others fall away, and life becomes that sole aspiration.