Even before the new normal of remote learning in a pandemic, college was an emotionally draining experience for many students. Pairing a minimum of 12 hours of classes with jobs, extracurriculars and social interaction is difficult for even the most capable of students, so why do so many professors insist on treating their students with apathy?

We all know the signs of an apathetic professor: overly-anal about formatting, courses designed to confuse rather than educate and the dreaded mantra of “don’t ask; it’s in the syllabus.” To these professors, there’s more to be gleaned from following the rules than from having a true academic discussion.

Rather than sympathetically helping their struggling students, too often do these professors passive-aggressively leave them with little help and a broken spirit during email correspondences. Professors don’t have to, nor should they, excessively shame their students for not recalling minutia of mile-long syllabi.

Regardless of the subject of instruction, the professor needs to understand the emotional and physical plight of the average college student. Instead of providing students with vague directions and expecting them to follow suit with no issue, professors need to be willing to help their students navigate their courses.

Instead of refusing to grade a paper due to poor formatting and waiting to give the student a zero when grades are due, professors should reach out to their students when they receive assignments with incorrect formatting and give them a heads up. The details of college coursework, while important, should not supersede the actual academic content.

“Professors shouldn’t have strict formats in order to email them; you should just be able to email them and get an answer,” biology major Louis Giacona III said. “Usually the students are more stressed than [professors] think they are, so I think if they were more approachable, it would improve the overall college experience.”

While a professor’s job is to impart coursework to encourage students to pass the class with relative ease, the purpose of higher education extends beyond grades to the real-world lessons that make the difference between success and failure in the post-collegiate world.

A good professor’s lessons do not end at the Zoom call’s close; they extend to facets of the student’s everyday life. The professors you remember fondly aren’t the ones who drone on for hours about macroeconomics like Ben Stein’s Mr. Lorensax from “Ferris Bueller’s Day Off,” but those more akin to “Dead Poet Society”’s John Keating, portrayed by Robin Williams.

“We teach critical thinking, imaginative thinking [in liberal arts education], which is of great, if non-quantifiable, value,” history professor Andrew Burstein said. “I’m constantly thinking about how to make discussions serve the purpose of giving students tools to grow self-confident in their critical thinking and writing skills, to become more interesting.”

Especially in a year so full of uncertainty, students need professors who are willing to give them the guidance they need during this important juncture in their lives. Students crave someone to learn real, valuable lessons from; unfortunately, many professors are specters of a dreadful future in the professional world.

“I’ve never considered myself a role model because my goal has always been to keep others from making the mistakes I made,” Manship School of Mass Communication adjunct instructor Freda Dunne said of her role as a teacher. “Maybe I’m a reverse role model.”

A professor should want to be remembered as more than just that one ECON 2001 professor who was more concerned with how you named and structured your Microsoft Word document than what was contained within.

The ideal professor strives to be more than just a “vomitorium” of information. They can be a truly impactful figure in the lives of their students.

Professors, give your students a reason to come to class and pay attention. Give them an experience they won’t soon forget. Provide them something that outlasts the graduation stage and into the mad world of reality. Teach them something they can actually use out there.

Domenic Purdy is a 19-year old journalism sophomore from Prairieville.

Opinion: A good professor is sympathetic, especially in a pandemic

November 9, 2020

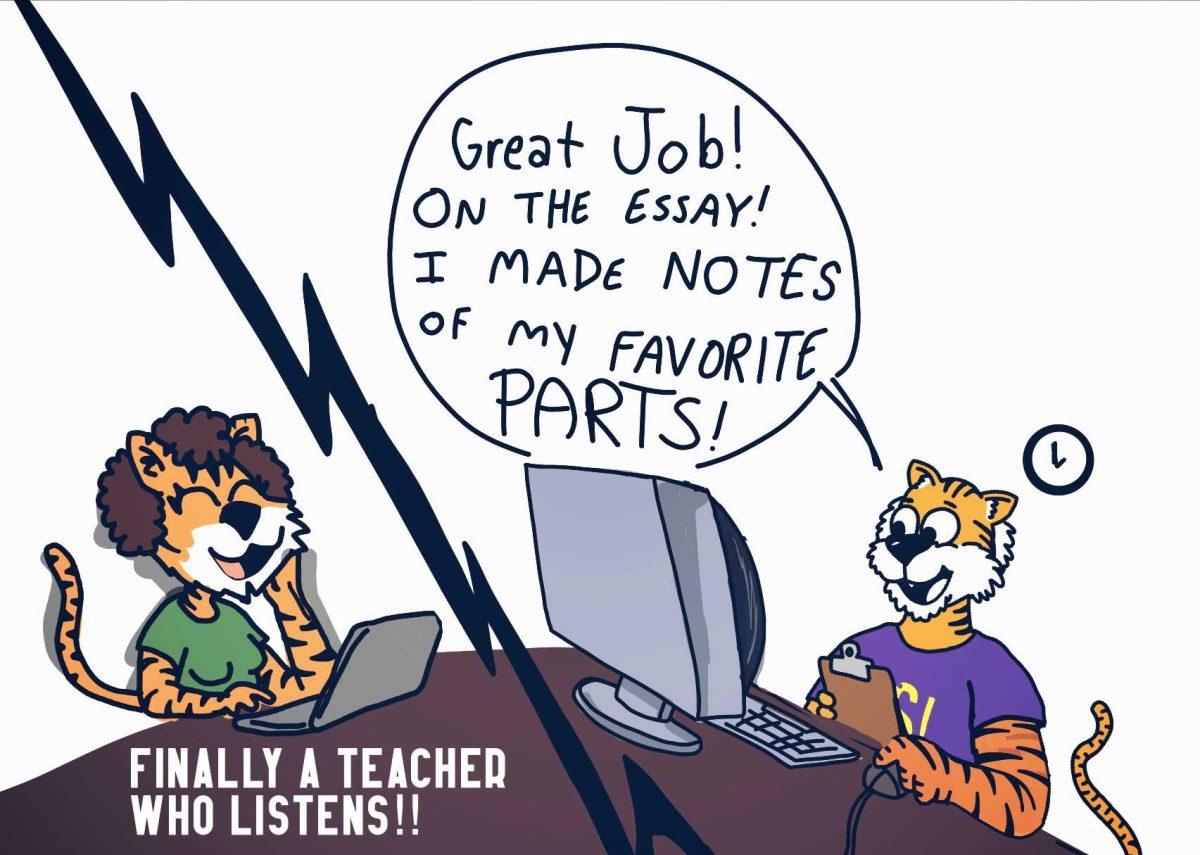

A Good professor listens