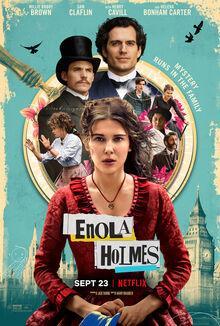

Stars: 4/5

Netflix original “Enola Holmes” starring Millie Bobby Brown as the titular role shook the popular perception of the Sherlock Holmes story, instead following his all but forgotten younger sister raised in isolation by her mother, Eudoria Holmes (Helena Bonham Carter). While her better-known brothers Sherlock (Henry Cavill) and Mycroft (Sam Clafin) play vital supporting and antagonistic roles respectively, their relation to her is hardly the focus. Instead, she explores London and experiences the suffragette cause first vicariously, then firsthand, by following her mother’s sparse trail in the wake of her disappearance.

Fans of the book series or, more likely, the BBC series “Sherlock,” will notice major behavior and personality differences in the brothers. Not as major as Will Ferrell’s rendition, but undoubtedly present. The PG-13 rating sees the traditionally darker side of the Holmes family stripped away to maintain a more childlike, innocent air. Sherlock isn’t a fan of opiates onscreen and Mycroft does not appear to puppeteer any governmental functions. Enola, however, hails from a spinoff series of books by Nancy Springer, and fits more appropriately with her lesser known literary counterpart.

The strong suit of “Enola Holmes” is undoubtedly its dialogue. Most main characters — the Holmes family and the Marquees, most notably — wield quick wits and flick their sharp tongues in entertaining exchanges of quips. While always comprehensible for its intended audience, the subtext of these bouts may sometimes be lost on younger viewers. This practice of sneaking in something for the parents in children’s movies has largely fallen out of vogue since early 2000s Disney animations, but it makes movies age much finer. Cavill and Brown’s conversations carry an authentic spark of intellect that brings believable brilliance to their notoriously bright characters.

At many points in the film, Enola breaks the fourth wall by directly looking and addressing the audience and infodumping. As an introductory tool, this is to no detriment. However, about an hour and a half in, she uses the same audience engagement method as Dora. In a moment of stress and urgency, she turns to the audience with wide eyes and asks, “Do you have any ideas?” The cheesiness of this five second aside is responsible for most of the lost star, the rest for lack of character flaws and development out of them. Neither Enola nor Sherlock have any apparent shortcomings to conquer over the course of the film. This is not necessarily problematic, though it is a crucial missing piece in Enola’s Shero’s Journey (feel free to use that) when the purpose of her mission shifts from finding her mom to “finding herself” and making her own path by taking a first case.

The difficulty with “reviewing” films like “Enola Holmes” is addressing that intangible element of childhood movie nostalgia. The most effective and likely intended method of digesting the movie is during the formative younger years. When the mind is nice and squishy and receptive, and the cynicism many people contract from the world later in life isn’t present, nothing must be taken with a grain of salt. If I watched “Enola Holmes” when I was eight, I’d have spent a lot of my time that year trying to make superhuman observations like Sherlock or learning the fascinating hobbies Enola keeps with her mother like chemistry and cryptology. For the impressionable viewers that leave the DVD in the car seat headrest player rolling every car ride to soccer practice, it could only serve to inspire an inquisitive mind and fulfilling life. Enola’s own exploration of the suffragette cause her mother champions gives an age appropriate (if sugar coated) but fairly realistic look into the woman’s fight to attain equal opportunity, primarily in late 19th century England though with themes relevant today.

It’s the perfect kind of live action feel good but conflict driven movie to grow up on. Adults and critics can watch a movie like this, enjoy it thoroughly, and appreciate its influence on young viewers. But they’ll never be giddy with excitement to revisit it as a grownup and tap into those nuggets of dopamine they forgot were buried in obscure scenes or sounds or lines of dialogue they forgot they’ve been referencing their whole lives.

Unlike many treasures of ‘90s and 2000’s kids’ upbringing, modern kid-oriented movies reflect a greater degree of political correctness and less understatedly raunchy references. I doubt I’ll ever find a reposted Tumblr meme of dialogue found inappropriate in more sensitive times from “Enola Holmes” with the caption “how did they get away with this?” like those that exist for “Shrek” or “Bee Movie.” This is an important ingredient in the cocktail that makes a timeless childhood classic worth shoving into the mush of a developing mind.