After Herman Kelly concluded his class, two students, Alaysia Johnson and Justin Martin, approached the professor to chat with him. It was a normal March day, a couple weeks before the coronavirus forced LSU to close, and it was a routine conversation, between two African and African American Studies (AAAS) majors and their professor. The trio, at the time, had no idea how significant this meeting would prove to be.

Kelly bemoaned the state of LSU’s AAAS program to his students. Only a minor or a concentration of a liberal arts degree, AAAS lacked the support that its professors believed it deserved. The program must be its own department, Kelly told his students. AAAS professors have argued this claim to their administrators in the College of Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) for years now, to no avail.

“We make bricks with our straw,” Kelly said.

Administration cited a lack of student interest and a lack of funds available as reasons to keep AAAS a program. Kelly was seeking student support, and Johnson and Martin were on board. He asked them to gather other students, especially their white peers, to write and sign a letter of support for the program. Martin, a senator at the time, had a better idea.

“We can do you one better than that,” Martin told Kelly. “We can write a resolution.”

If passed, the resolution would have the support of the LSU Student Senate, which represents all 30,000 students. Martin wrote the resolution, and the body would have heard it not long after, if not for the campus’ closure. Instead, the senators passed the resolution when they next convened, in the summer over Zoom.

It was perfect timing. The senate met on the same day LSU students assembled in the Quad to protest racial injustice and police brutality and in the middle of a nationwide resurgence in the Black Lives Matter movement, ignited after the deaths of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor.

Two weeks after the resolution was passed, Troy Blanchard, dean of the HSS College, announced in a statement that he would partner with the leadership of AAAS to promote the program to a department. Those around the program believe that Blanchard has wanted to elevate it since he became dean in December 2019. The protests and the student support were enough to push him over the edge.

“I’m willing to commit to this as long as I feel strongly that the college has committed to this,” said Stephen Finley, director of AAAS. “At this point, I’m willing to give the college the benefit of the doubt and say that the dean seems serious about it.”

Finley and Kelly have long held that universities will not change without the efforts of students. Kelly himself, when he was a student at Boston University’s School of Theology in the ‘80s, marched on the dean’s office, demanding more courses in Black studies and more Black faculty. His meeting with Johnson and Martin was the first step in accomplishing what a decades-long movement at LSU, until this point, could not.

“It’s almost like a cycle,” Kelly said. “Like it’s coming back around.”

The present fight for AAAS has its roots in the civil rights movement of the ‘60s.

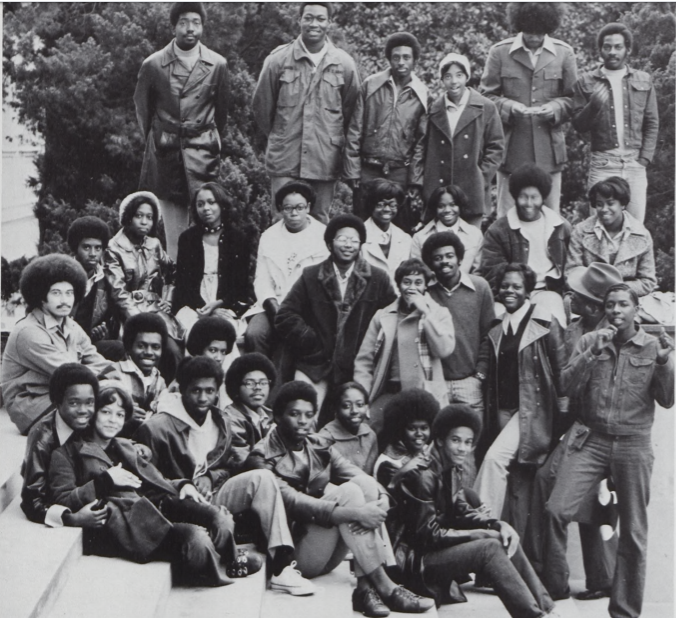

In the ‘60s, Black studies courses were scattered around LSU’s various departments. The Harambe Student Organization, named for the Swahili term that means “let’s pull together,” was founded in 1967. It pushed the administration to establish a centralized Black studies curriculum.

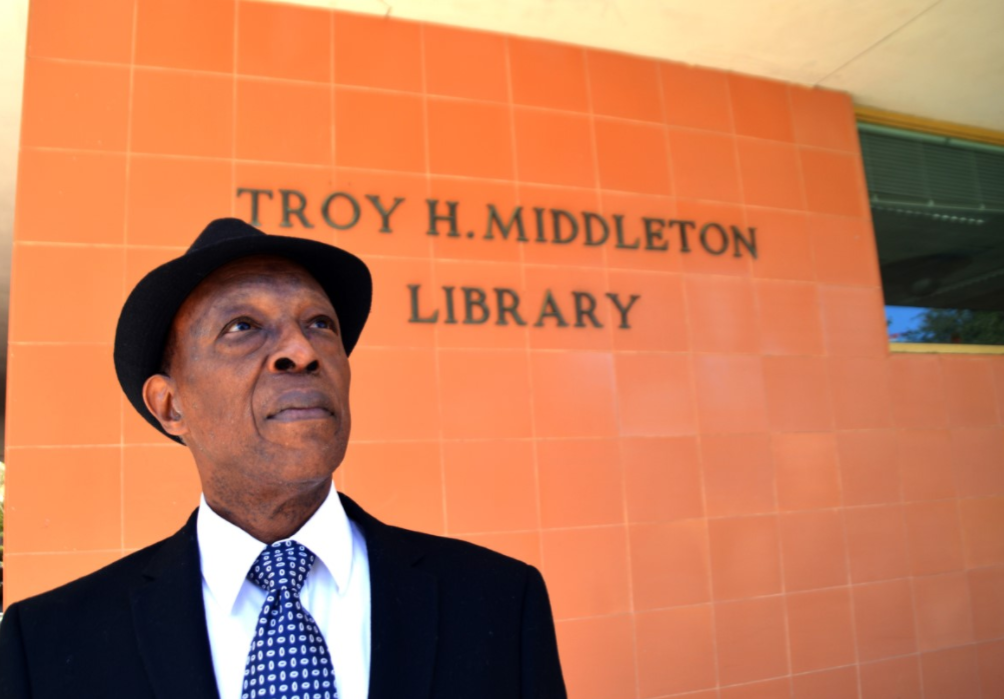

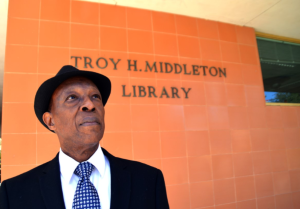

When the AAAS program’s first director, Thomas Durant, arrived at LSU in 1973, he landed in the middle of this student-led movement. The AAAS program wouldn’t be founded until 1994. Durant resided on the committee to establish it, and was appointed the program’s first director in 1997. But he was not content.

“If you’re standing still, you’re not growing,” Durant said.

In 1999, he requested $5,000 to fund a self-study of his program and invited William Nelson of Ohio State University to evaluate AAAS in Baton Rouge. Nelson wrote a 20-page report, recommending that the program become a department right away.

“Since its inception in 1994, [AAAS] has festered as a modest, underfunded, dependent academic unit struggling for the irreducible minimum resources it needs to remain viable,” Nelson wrote.

Nelson found a five-year-old program without a budget and with only part-time professors who split their time working in different departments. Even Durant was jointly appointed — in AAAS and sociology. Nelson recommended that LSU fix these problems, build a research arm in AAAS and organize community outreach programs.

Durant brought the self-study to his dean, who declined to create a department, citing budget cuts from the state legislature.

“I didn’t accept that,” Durant said. “I feel that we should have received top priority, so that even if we were cut, the money that we got, some of it should have been allocated for the purpose of establishing a department. So if you don’t set a goal of having the program in a higher priority category, then it never will get funded.”

“Even in a storm of budget crisis, a first-class university must set aside special funds to support essential programs,” Nelson wrote in the report. “In my view, [AAAS] is not only essential, its potential impact is so great that it should be given priority attention in university budget decision-making.”

In the ensuing years, the directors of AAAS took the report to dean after dean of HSS, and each one commended the program but stopped short of promoting it. They each gave similar reasons: HSS needs more money, and AAAS needs to graduate more students.

“It is clear that the student enrollment base required to justify and sustain an institutional departmental structure already exists on the campus and in the surrounding environs,” Nelson wrote in 1999.

“Well, how can you get more majors and graduate more students with degrees when you don’t have any faculty, not an established budget and all the faculty are part-time faculty whose major allegiance is to other departments?” Durant countered.

Durant retired in 2009 with a few more joint-professors and a few more classes under AAAS, but in his eyes, not enough.

Today, Durant speaks slowly. Given his advanced age, he tends to ramble. But his voice, tinged with fatigue, is still strong, even after decades of fighting institutional racism. He is a living monument to Black studies’ 50-year fight for independence. And now, he may finally get his wish.

“I was pleasantly surprised, but certainly happy after 25 years,” he said of Blanchard’s decision. “Finally, some positive movement toward that goal is underway. I’m optimistic, but at the same time cautious because this is a proposal. We don’t have it yet.”

Durant recently made a $10,000 donation to AAAS to help establish an endowed chair of the program. He said he’s willing to assist the promotion process, if he’s asked, and he’s sent Dean Blanchard a letter, pledging his support.

“Whether or not people realize it, African American people represent one of the strengths of this state and LSU,” Durant said. “And it’s too bad that they didn’t realize this.”

Alaysia Johnson and Justin Martin found themselves in another meeting not long after Blanchard announced the promotion of AAAS.

Blanchard, Associate Dean Elsie Mitchie, Johnson, Martin and two other student government representatives, Angel Puder and Devin Scott, met virtually to discuss the next steps in promoting AAAS. Blanchard told them he expects the process to be complete by the end of 2022. It’s up to the college to approve the request and make changes to the curriculum and budget. Then the proposal ascends to the University — to the provost’s office and the Board of Supervisors.

For Johnson and Martin, spearheading the elevation of their program is a source of pride. The two deans told the students that they gave them a new perspective on what the program provides to the student body.

Johnson was born and raised in Maryland, but her family is native to Baton Rouge. Segregation prohibited her great-grandparents from attending LSU. So after her great-grandfather, Charlie Brown Johnson, was deployed to WWII, he and his children moved to Maryland, where his platoon was stationed. Charlie fought in WWII, Korea and Vietnam.

“I go to LSU for [my great-grandparents], to keep breaking ceilings and accomplishing things for them,” Johnson said. “It’s important for me to break barriers for everyone before me and those behind me. This is why the AAAS department is so important. To keep sharing history and to create it.”

Johnson revived the Black Caucus and the Black Women Empowerment Initiative. She is a political director of LSU NAACP, and she works in the surrounding community and in a public school. After graduating, she wants to go to law school and pursue a career in civil rights.

Some students may be left wondering if the AAAS program is only for Black students or those pursuing careers in activism.

“Obviously that’s not the case,” said Martin, a white rising senior. “These courses are for everyone, and everyone can get something out of them.”

Martin said in AAAS classes, he’s dove to new depths of civil rights issues, drawing inspiration from everyday people starting a grassroots movement to change their world drastically.

“And it was something we could do too, even if it was something potentially small like the AAAS program,” Martin said. “But it could really have a big impact for students going forward.”

Martin wants to attend graduate school for history, specializing in reconstruction and the civil rights movement. Then, he hopes to teach at the community college or university level, and he may even run for office, enacting policies to mold a more just society.

Both students underscore the importance of education, the first step to a more equitable and accepting world. AAAS provides crucial lessons in the history of racial injustice in America.

“We will be the people that they will come to and say, ‘How do we deal with injustices?’”Kelly said. “‘How do we deal with racism?’ We teach a lot of those courses.”

Kelly is proud of his students and hopeful for the future. He’s confident AAAS will finally be promoted, and he knows his colleagues and students are up for the task.

“I would put my students up against any unit on campus,” Kelly said.

So too is Durant, who was “delighted” when he heard the news.

“I think I’m more optimistic than at any time in the past, but I’m cautiously more optimistic,” Durant said.

“Because I won’t believe it until I see that it is done.”