The LSU School of Veterinary Medicine and the engineering department have been commissioned by LSU and the city of Baton Rouge to track COVID-19 outbreaks through wastewater samples. This method is being used throughout universities in the U.S. and internationally.

COVID-19 can be detected in wastewater up to 10 days before an individual begins displaying symptoms of the virus and a clinical diagnosis can be made. This method is primarily used to detect potential outbreaks and prevent circulation of the virus, according to pathobiological sciences professor Konstantin Kousoulas.

“That’s the power of this technology, that it can be a predictive tool to project where the problem may be and perhaps take measures to limit further spread,” Kousoulas said.

Some of the research team’s predictions have already come to pass throughout the state. Konsoulas said the team predicted a surge of infection that has been confirmed by case studies both in the city and at the University with incoming students.

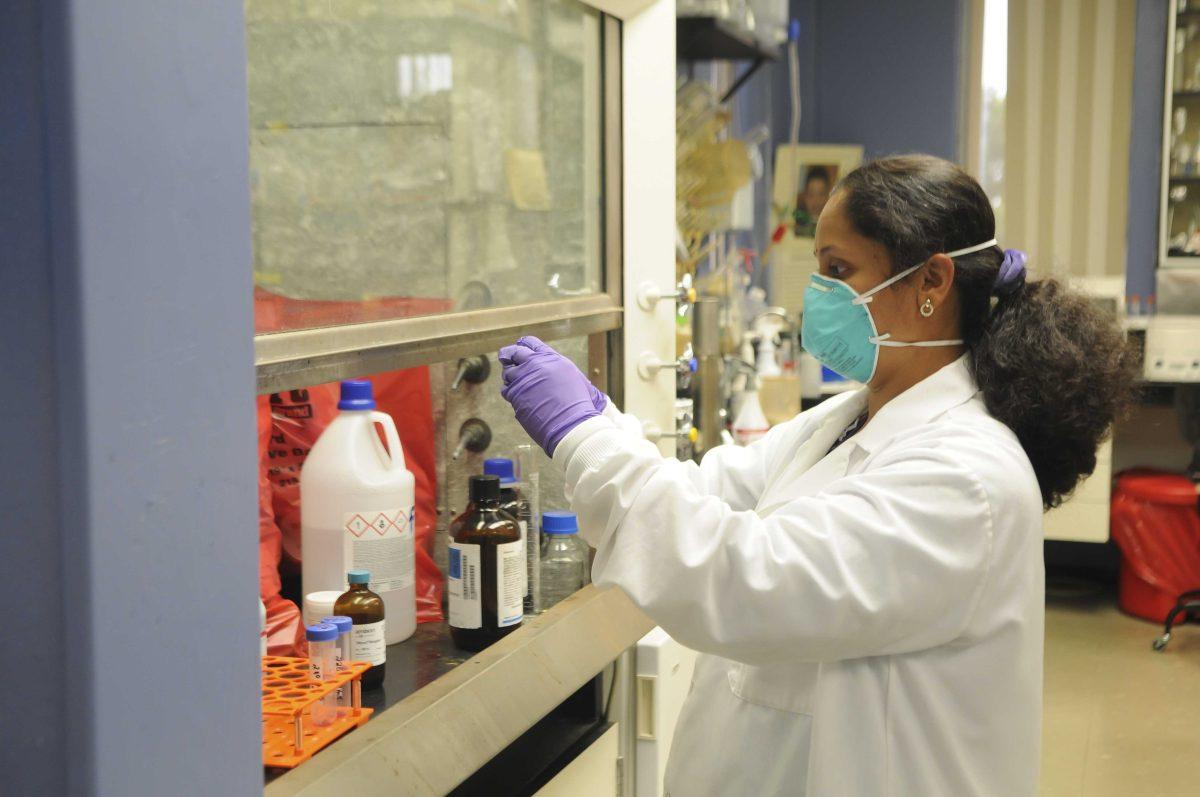

Environmental engineering professor John Pardue said they pasteurize the samples.

“Just like milk is pasteurized, it kills anything in the sample that could cause you to get sick,” Pardue said.

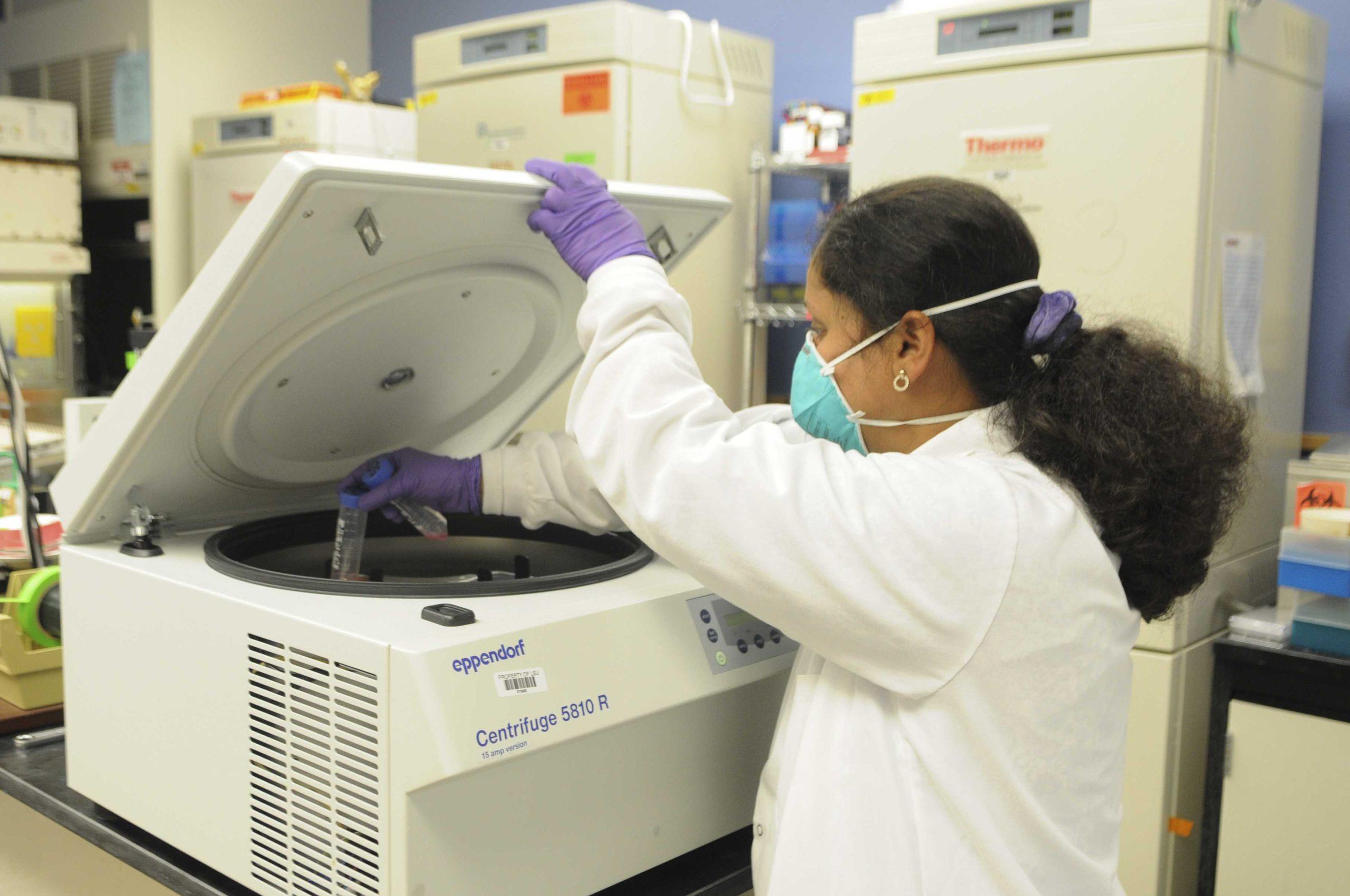

Then, the team uses a chemical to extract the virus from the water and perform a genetic test looking for the RNA from the SARS CoV-2 virus.

“We’re looking for how many copies of that virus are floating around in the water we’re sampling,” Pardue said.

Based on how many millions or billions of RNA fragments are in the sample, the researchers can determine the approximate amount of individuals who have the virus in the building that was tested. This is especially useful in dorm complexes.

The VetMed school also has technology able to decipher which strain of COVID-19 is present in the samples.

“We have the capacity to analyze and track down which strain is circulating. We don’t do that now, but we can do that,” Kousoulas said.

Kousoulas said anyone who has previously contracted COVID-19 should be “resistant or at least partially immunized against any subsequent infection.”

The research team is testing every area of campus once a week, monitoring the viral RNA levels and detecting potential outbreaks. If it comes down to it, everyone in the dorm or workspace will be tested and appropriate actions can be taken based on the results.

“The prediction is, because a lot of these cases are asymptomatic, the number of asymptomatic cases will increase and the result of cases at the student clinic will increase,” Kousoulas said.

This surveillance technique allows researchers to report findings to the appropriate venues and test the effectiveness of certain COVID-19 regulations. If a large surge in cases is noticed in advance, the researchers can warn hospitals in the surrounding area so they’re prepared for an influx of patients.

The data can also help demonstrate the effectiveness of certain regulations, such as mask mandates. Shortly after East Baton Rouge implemented the guideline parish-wide, cases steadily dropped. The same result was seen after Gov. John Bel Edwards implemented the mask mandate state-wide.

“We’re trying to provide another piece of information for the people making decisions,” Pardue said.

Kousoulas said that knowing in advance when outbreaks may occur gives LSU an important advantage.

“Any detection mechanism as an early warning of what may be coming is important,” Kousoulas said.

Although Kousoulas and Pardue predict an uptick of cases in the coming weeks, their goal is to help keep everyone on campus.

“[We’re] not trying to close the campus with this, we’re trying to do the opposite,” Pardue said. “We’re trying to keep it open longer if we can break the transmission.”