So many of us have grappled with the complex, often frustrating dilemma of trying to reconcile our love for a piece of art with our discontent for the artist that created it.

From Caravaggio’s violent proclivities to Ezra Pound’s fascist sympathies and the sexual abuse accusations against Michael Jackson, the prolific but problematic artist is a timeless quandary we are all bound to face at some point.

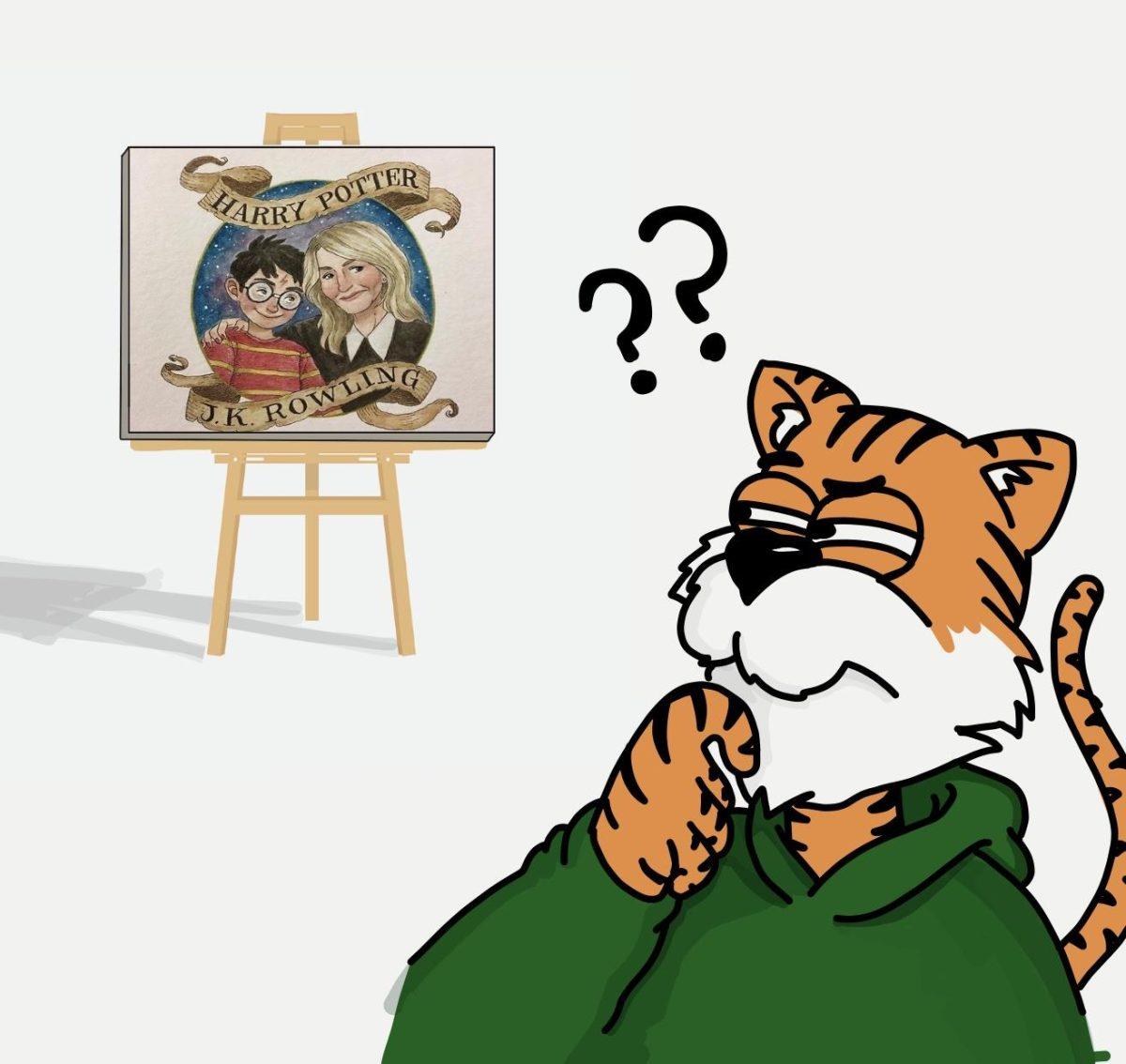

The past few months have given this classic dilemma renewed relevance for members of my generation in particular. In the wake of Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling’s recent remarks on Twitter, which were accused of being transphobic, many who have grown up devoted to the franchise are now having to sort out some cognitive dissonance.

Is it possible to enjoy a piece of art knowing its artist lived and thought in a way that you disagree with? Does celebrating art necessarily glorify the person who created it?

After all, it’s not necessarily self-evident where art ends and where the artist begins since our culture often seems to view art as an extension of the mind that created it.

Traditionally, people have approached these questions in a few ways.

In the case of living artists, most won’t want to financially support behavior they do not agree with. However, someone deciding not to spend money on something because of ethical convictions can be applied to many different scenarios and does not necessarily address the fundamental aesthetic questions.

What if you already own the art in question? In theory, your enjoyment of it would bring no further benefit to its creator. Responsible spending aside, how should the moral fabric of an artist’s life affect the way we experience their art?

In the case of J.K. Rowling, Harry Potter fans have come to terms with these questions in various ways. Some have taken to social media to express their discontent by throwing away or even burning their copies of the once-beloved books. Others are less willing to abandon their love for the series, choosing to simply enjoy the books without considering or identifying with the author.

This popular cliché of “separating the art from the artist” is helpful regardless of who the artist is. However, in order for this approach to be effective, we need to fundamentally reconsider how we understand artists’ relationships to their work.

Our contemporary understanding of the artist is an outdated heirloom from the Romantics of the 19th century, who understood the artist as a divine spark of originality and creative genius; some sort of prophet or oracle whose work is an exterior expression of an extraordinary interior life.

This view that the value of art is intertwined with the artist’s own experiences might very well be the origin of our current troubles in attempting to separate the art from the artist.

In his 1920 book “Art and Scholasticism,” French philosopher Jacques Maritain presents a scathing critique of this sort of Romantic sensibility. He looks back to the medieval understanding of artists as artisans rather than prophets; for Maritain, being an artist is not some higher calling that involves expansive insight. On the contrary, art is, for him, all about quality craftsmanship.

With Maritain’s insight in mind, dwelling on the personal morality of an artist almost seems ridiculous. When we buy furniture, does the personal character of the furniture maker even cross our minds? Of course not; our only concern is that the piece looks nice and functions correctly.

In this sense, the furniture is autonomous. It has a life and identity of its own, completely separate from the individual who created it. It is our furniture now, and it is useful to us so long as it fulfills those basic tenets of aesthetic and practical quality.

Why should the fine arts work differently? Understanding art in terms of craft with its independence from the mind that produced it could prove to be enormously fruitful when enjoying the works we love.

That said, the Harry Potter series is not J.K. Rowling; so if you were considering burning your copy of The Sorcerer’s Stone, it might be worth reconsidering.

Evan Leonhard is a 19-year-old English and philosophy major from New Orleans.

Opinion: We should always separate the art from the artist

September 28, 2020

Separating Art from the Artist