It was an overcast April day in 2014, and professor Stephen Finley was walking with a graduate student to the Starbucks at LSU for a meeting, when the two Black men saw a couple of LSUPD cars drive up.

The cars stopped, and a few officers and a lieutenant hopped out, Finley said. They told the men to stop and step onto the sidewalk.

“What’s going on?” Finley asked. “I’m a professor. I work here.”

“I work here too,” one of the officers responded.

Finley asked why they were being detained, and the officer said they had received a report of two Black males leaving Coates Hall. Finley said he asked if they could leave, and the officers refused, holding them for 10-12 more minutes.

After he was released, Finley expressed his frustration and told the officers that they would be hearing from him. He later met with the chief of police, the vice provost of diversity, the dean of his college and a lawyer. He considered legal action, but decided against it. He was up for tenure.

“Under the circumstances, I had to consider what I could have potentially put in jeopardy,” Finley said.

Through a spokesperson, LSUPD commented that they only keep records of arrests and citations, and they have no documentation of the incident.

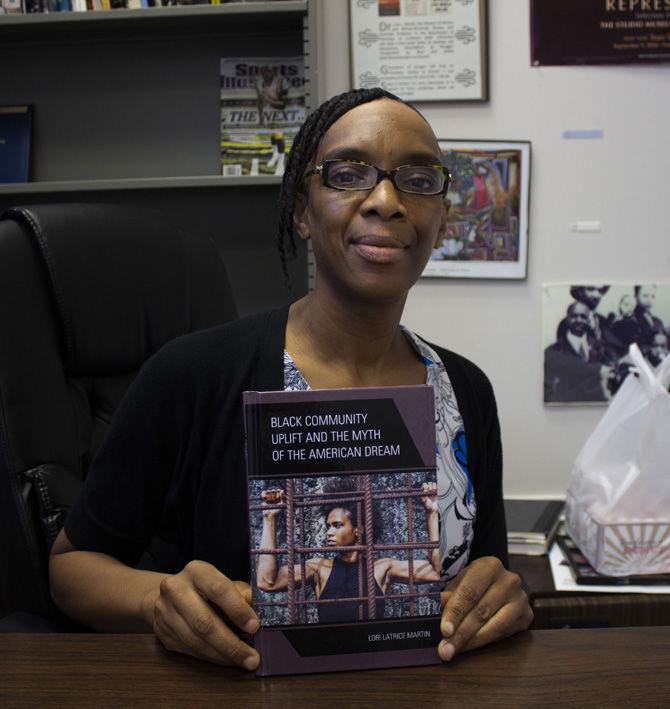

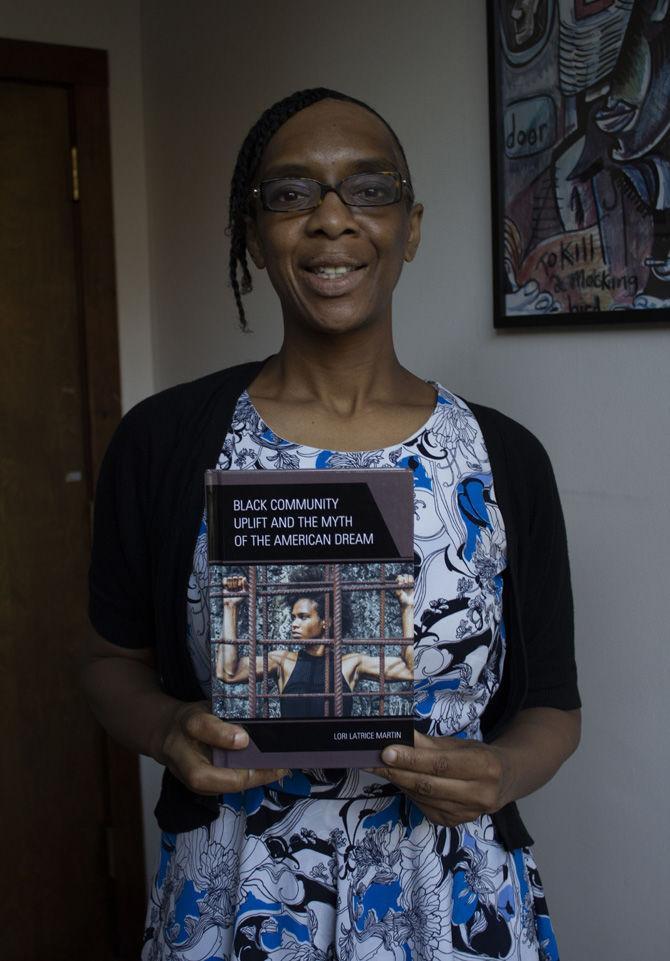

Today, Finley is tenured, working as the director of LSU’s African and African American Studies (AAAS) program. His job is secure, and his words are candid. With his colleague Lori Martin and a young Syracuse professor named Biko Gray, Finley is writing a book that is critical of white university administrators.

In 2015, as Gray was entering the world of academia, Finley said he had to have what he called “the talk” with him. He likens this conversation to the one Black parents are forced to have with their children to prepare them for encounters with police. But Finley was not warning Gray about cops. He was bracing him for the challenges he would face as a Black professor in a predominantly white institution.

“It’s the kind of consideration that other people don’t have to make to do their jobs as scholars, as researchers,” Finley said.

In his young teaching career, Gray said his campus police force has already dubbed him a “problematic professor.” Donors have sent him hate mail, people within the University have anonymously ridiculed him and tried to get him “reeled in” after reading some of his tweets.

“We’ve been hired to do this work, but then ultimately we are castigated for doing the very work that we’ve been hired to do,” Gray said.

The trio joined forces to co-author a book after seeing a few high-profile cases in which a Black professor — Tommy Curry, George Yancy or Saida Grundy, to name a few — received harsh backlash for critiquing whiteness and no support from their white administrators, who said that their teachings don’t “affirm our values” of acceptance and inclusion.

“It could be understood as the institutions that, in some ways, promote whiteness, and in doing so, place Black faculty in a very precarious position,” Martin said.

“My job can be dangerous, just because of the work that I was hired to do,” Finley said.“And I want to feel comfortable that those who hired me to do my job, to do this work, would support me.”

Finley, Gray and Martin agreed that young Black professors are faced with a decision as they enter the world of academia.

“Do I do the work that I do, that I believe in, that I think can make a difference, that can help educate students who might make a difference in the world?” Finley asked. “Or do I do something easier with far less risk?”

“Black professors also might have concerns about where they publish and what they publish, because they’re not sure how that might be received by their colleagues who are charged with evaluating them for tenure and promotion,” Martin said.

But that noise is only external. Black faculty must fend off racism on two fronts — angry trolls in cyberspace and their own peers and students on campus.

Finley said other LSU faculty have used “racially derogatory language” in his presence.

“Use your imagination,” Finley said.

_____________________________________________________________

Cassandra Chaney teaches in LSU’s School of Social Work. A few years ago, she remembers teaching a graduate class of 10-12 students. She had her hair styled in an afro.

She was shocked when one of her white male students made a comment about her hair, calling it “unsanitary.” She calls the remark “extremely unnerving.”

“I felt attacked,” Chaney said.

She also recalls the time that a white colleague told her she was hired only because a white professor advocated for her.

Not long after Chaney was hired in 2006, a Black LSU senior came to visit her during her office hours. Chaney recalls the student sat down and immediately burst into tears.

“I so wish you were here four years ago,” the student told Chaney.

The student told her about all the racism she had endured over her four years at LSU — from professors’ refusing to call on her, to a professor’s arranged seating during an exam that isolated her and clumped together other students, who could then easily cheat. She considered leaving the University many times. In Chaney’s office, she was again close to leaving, but she wanted to be the first member of her family to graduate college. That kept her motivated.

“I know she’s not the only student who’s had that experience,” Chaney said.

Walk past Chaney’s office, and you may see her counseling and mentoring a Black student who is having trouble navigating a nearly all-white campus. Walk farther, past the offices of her white peers, and you’ll see them toiling away — researching, writing, doing the work they were hired to do.

“If [Black students] feel that they are being treated unfairly, then they may go to a Black professor looking for guidance and support, and so that’s added work that Black professors will often times — and many, of course, are happy to do that — but that may be something that non-Black colleagues may not have to address,” Martin said.

On top of that, Chaney said a fellow professor has told her to produce three more publications than her white peers. Gray also believes young professors of color are pressured to overproduce and exceed their institutional standards.

“As my mama always told me, you have to work twice as hard…so there’s no basis upon which my career could be called into question because I’ve met every mark that was measurable or exceeded every measuring standard that is in place in front of me professionally,” Gray said.

“But it’s also the added burden of realizing that I can’t be mediocre,” Gray said. “I have to be exceptional. If I’m not exceptional, any excuse can become the excuse for me to be gone.”

Black faculty must double as counselors, and they must double the work of their white peers. And they have to do it in half the time.

“Those two things are twin, double burdens, that my white colleagues just don’t have,” Gray said.

_____________________________________________________________

In the face of police killings, protests and renewed conversations about race in America, universities have released statement after statement, extolling their own values of diversity and inclusion and promising to be an accepting institution. Gray is skeptical.

“‘We’re good. We’re working towards this thing,’” he pantomimes, “All the while underpaying, not hiring, and overtaxing and overworking the Black people who are employed under their care.”

Young, impassioned, hungry — Gray offers four solutions to any university that truly seeks to foster an inclusive community.

One: strengthen the humanities and social science departments, he advises. Make it the “ethical heartbeat” of your institution.

Two: Change the parameters by which Black faculty are measured for success. Find a way to track and log the informal mentoring work they are doing and tie it to tenure and promotion standards.

Three: Don’t simply strengthen the departments. Strengthen the ranks of faculty who teach race and put their classes in the core curriculum for every student. Academia “has made it very clear that these particular departments aren’t their priority,” Gray said.

Four: Acknowledge that Black faculty do more work. Compensate them appropriately.

These professors devote their lives to teaching vital, humanitarian lessons. They’re asking their universities to devote more resources to them, so that they can not only succeed, but also thrive in their roles.

“It would be important that these scholars are recognized as the intellectual leaders on issues related to race — and race in America, in particular, and that at the time such as the one in which we’re living, should be the go-to source for thinking about ways to make the University more equitable, more welcoming to Black students and students more broadly, and to Black faculty,” Martin said.

“We have to do this,” Finley said. “We have to do this because it’s about these students, and it’s about the world, and for me it’s about something even deeper. I have to do it because it’s true. I can’t not do it. I have to do it

“If we don’t have people who are doing that kind of work, we will continue to repeat this devastatingly violent and lethal circular logic that we are seeing,” Gray said.

They teach about issues that bring people to the streets and rights that people are risking their lives to fight for.

“The reality is that cops run amok because no one has listened to Black folks,” Gray said.

“No one has listened to Black scholars.”