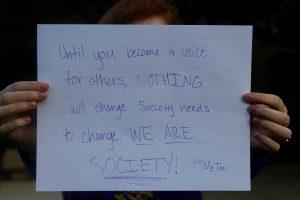

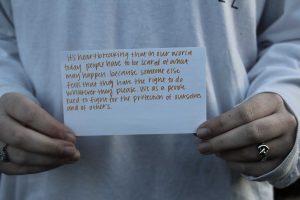

In these trying times, thousands of college students and those in widespread society are doing their best to combat sexual assault and harassment through increased discourse, widened definitions, public testimonies and defense courses.

One may find it baffling that such a devastating global theme is still unresolved and undefined, but through new discussions and definitions, our society has come to a better understanding.

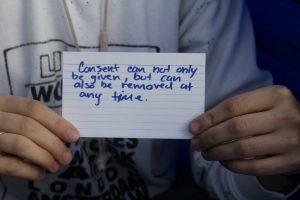

The FBI Uniform Crime Reporting Program’s (UCR) Summary Reporting System’s (SRS) definition of rape went unchanged from 1927 to 2012, reading as “the carnal knowledge of a female forcibly and against her will,” but recently, the definition has adopted more specific language.

As defined, victims are unable to consent from temporary or permanent mental or physical incapacity, including drugs, alcohol or age. The new definition recognizes male victims, includes the use of foreign objects, and physical resistance is not required for the victim to demonstrate lack of consent.

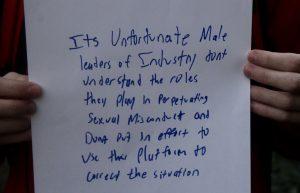

“I think that sexual harassment seems to be really hard to define these days because they have a lot of different opinions on the severity of what sexual assault should mean,” University student Angelle King said. “It’s a tough subject to talk about because nobody is clear on what sexual assault is. The main reason it’s such an explosion right now because [women] are like, ‘I didn’t know that could be defined as sexual harassment,’ so they didn’t understand that [their experience] was something they could come forward about until later,” she said.

The reality is that one in five women and one in 71 men in the U.S will be raped at some point in their lives, according to the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. Annually, rape costs the U.S. more than any other crime ($127 billion) compared to murder ($71 billion). The survey also found that one in five women are sexually assaulted while in college.

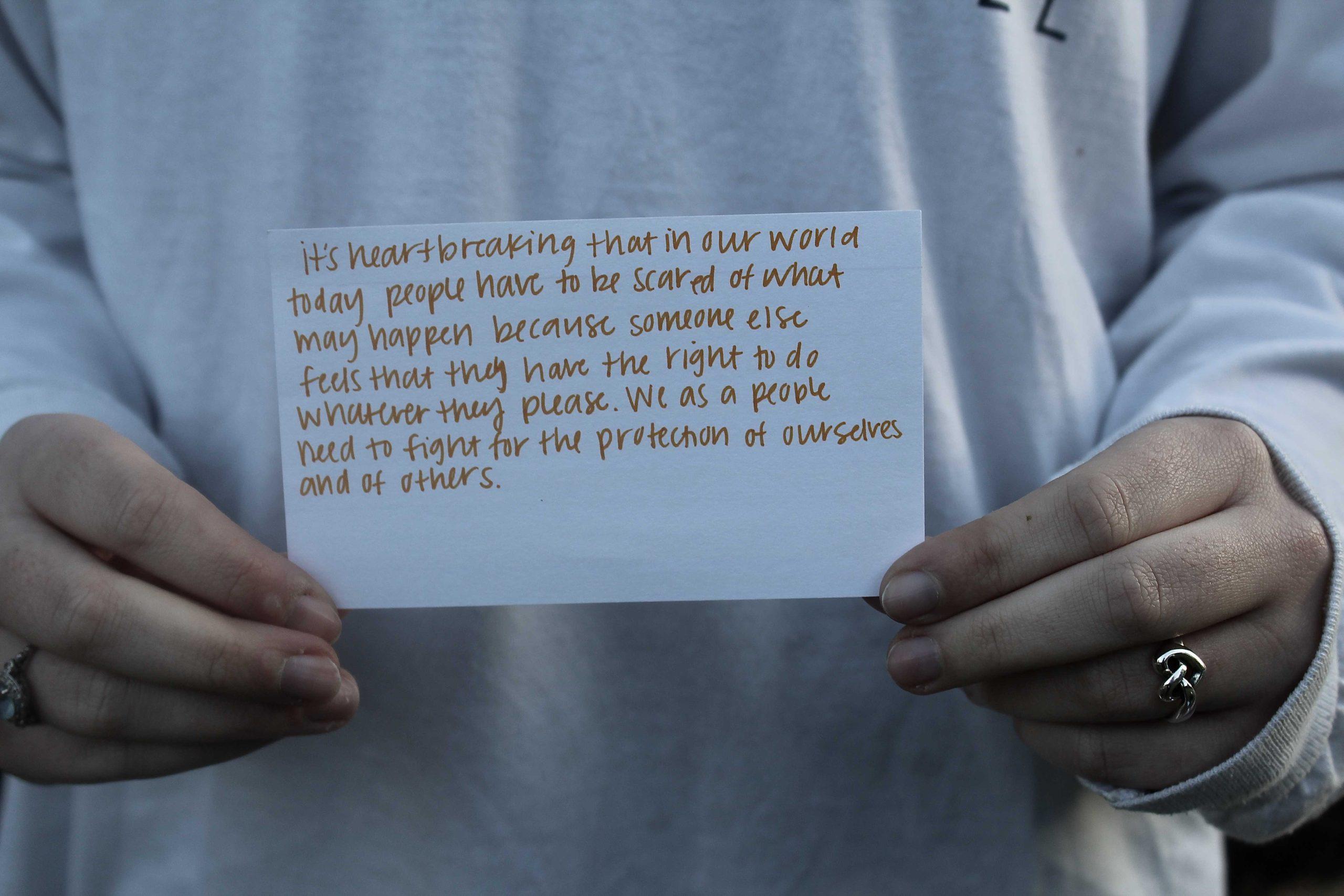

“Why should I have to feel like I have to protect myself and be on guard at all times when I’m just walking to my dorm,” University student Ashley Morgan said.

Morgan said she gets paranoid walking alone at night, especially after hearing about and experiencing sexual assault and harassment. While acts of sexual misconduct often occur on college campuses, many stem from childhood, leaving the victim with life-long effects, such as mental illness.

Take student Chris Smith* for example, whose girlfriend was molested by her stepfather from age seven to 17, which left her with scars of mistrust and trauma. After her stepfather’s actions were exposed, he was sentenced to 30 years at Angola prison, divorced from her mother and subsequently deported, but this is rare; cases like this often go unnoticed, leaving the victim without justice.

“There are still a lot of effects from it— say you come home at night, you jiggle the door and she’s crying when you walk in,” Smith said. “It sucks that somebody you thought loved you would tamper with your emotions and security so badly. A lot of relationships come with sexual things, and [if] you’re traumatized from trusting somebody, even people that don’t have [bad] intentions can seem like they [do].”

Students have access to information on sexual education through school programs, their parents and peers, but some feel that our existing sexual education just isn’t cutting it.

“[Sexual] education could be better, but its hard because [anyone] could take things and apply it or be like ‘whatever, I’m gonna do what I want,’ so I think it’s hard to get everyone on the same page,” University student Haley Gagliano said.

Furthering education and discussion reduces the risks of sexual abuse and assault. There’s a host of programs and resources out there for us, some even on LSU’s campus. Students can take a Rape Aggression Defense Systems course, offered at campuses around the Baton Rouge area, including LSU.

R.A.D. is offered once per semester, with a cost of $25 for students and $45 for the general public, which pays for the manuals and specialized equipment replacements. Recently, a R.A.D. class was held in the LSU Ag Center, allowing for a private session free from public disturbances, creating a comfortable environment for students and survivors, said Kathryn Saichuk, a R.A.D. teacher of 20 years.

“For college students, one of the biggest culprits that compromises our safety is alcohol,” Saichuk said.

But, R.A.D. tries to eliminate some of those risks by introducing students to simple changes they can implement to increase safety.

The only drawback is that R.A.D. is only for females, or people who identify as females. However, a new program— the Equalizer course— is launching later this year. Equalizer, organized by the LSU Police Department, is a male-dominated class similar to R.A.D., but focuses on combat rather than defense.

Though sexual assault is increasingly prevalent in society, we can combat the epidemic by educating ourselves and those around us, training through programs like R.A.D., and practicing preventive methods.