The last thing most people think of when they enter cemeteries is that one day they will disappear. It’s hard to imagine hundreds of final resting places being submerged or washed out to sea, but this is exactly what’s happening in Louisiana’s coastal zone. The Louisiana Endangered Cemetery Project seeks to raise awareness of this growing issue.

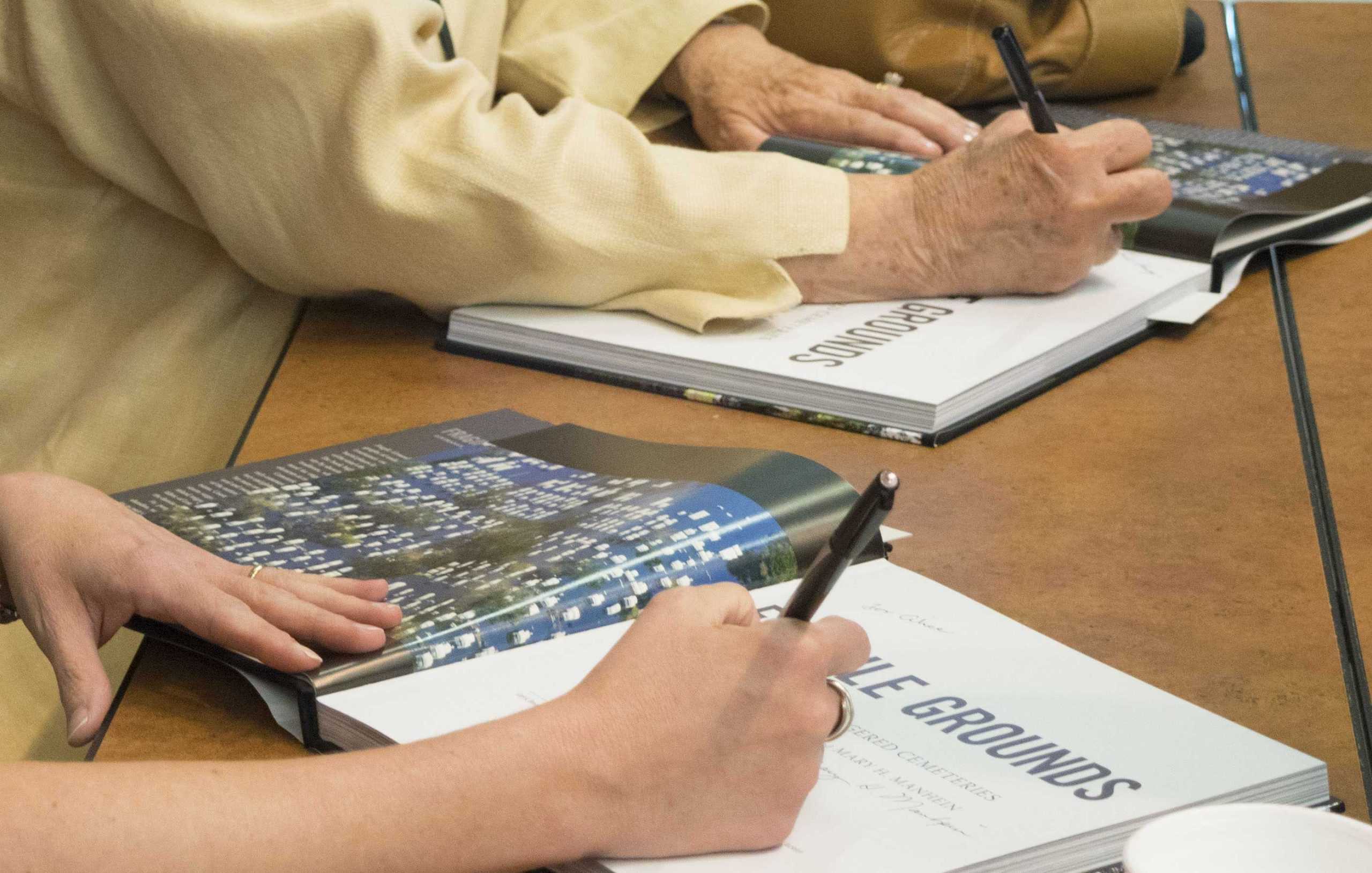

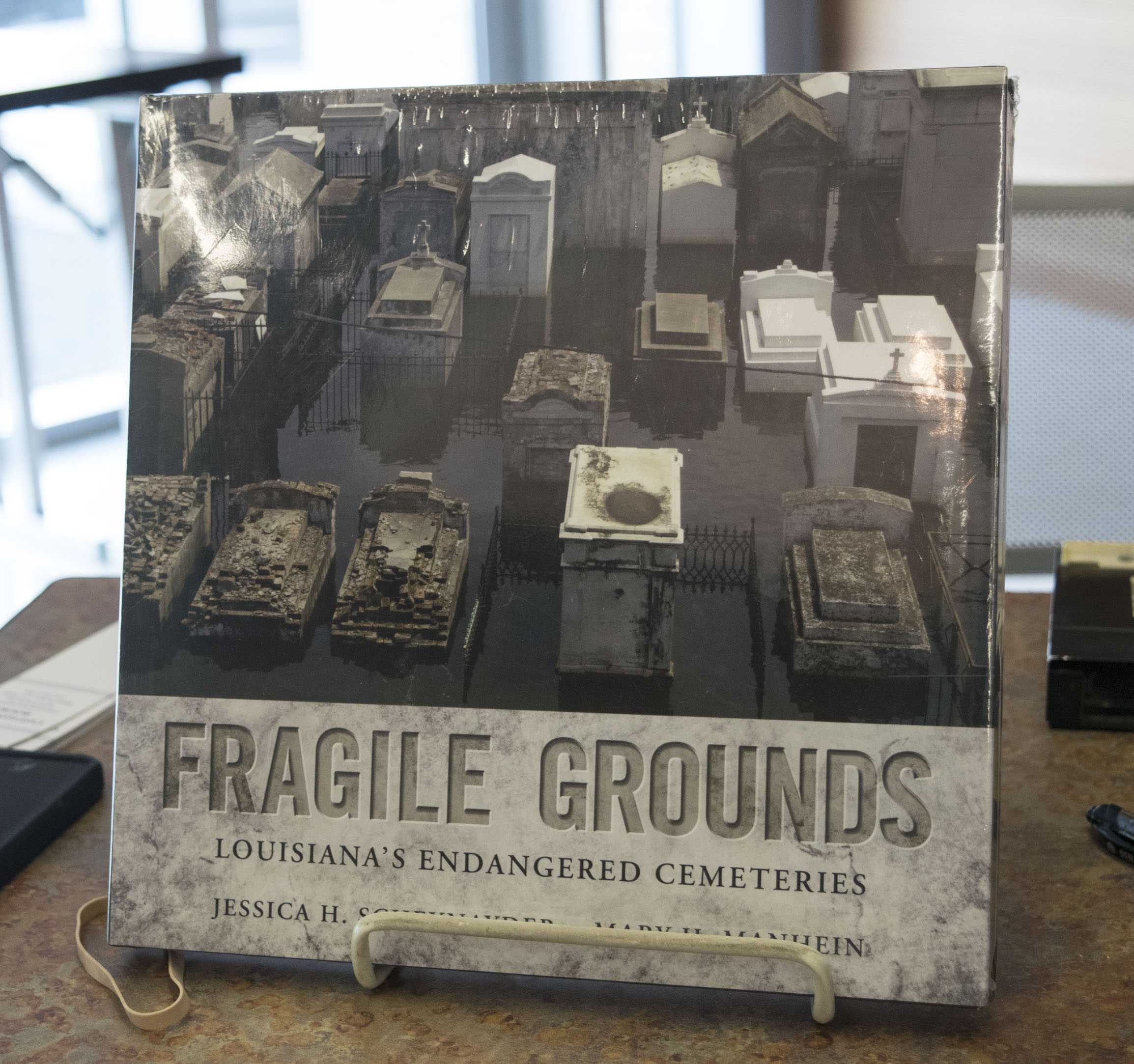

Former University student Jessica Schexnayder started the Louisiana Endangered Cemetery Project after becoming privy to the state of Louisiana cemeteries while writing an essay for retired FACES lab director Mary Manhein, co-author of “Fragile Grounds: Louisiana’s Endangered Cemeteries.” They are currently focused on promoting the book.

“We’re losing land at the rate of an acre every 30 minutes to the Gulf of Mexico, and 80 percent of the nation’s coastal land loss occurs in south Louisiana,” Schexnayder said. “So I was putting two and two together, and I thought, ‘Well what’s going to happen to the cemeteries that are on our coastline?’”

Schexnayder approached then-director of Louisiana Sea Grant Chuck Wilson with the idea to document the cemeteries because it tied to their mission of coastal sustainability. When the project was approved, she recruited her mentor Manhein to the cause, and the Louisiana Endangered Cemetery Project was born.

They decided to use GPS to determine the positions of the cemeteries and map the shape of the cemeteries, instead of using the single-point location method used by the United States Geological Survey.

“You don’t know what you’ve lost,” Schexnayder said. “So what we did was we employed a method of creating points around the polygons of each site, so that it created a geometric shape that will always be there when the land is gone or eroded. You don’t just have that one point. You have the whole shape of the site.”

Schexnayder and Manhein emphasized the importance of cemeteries to understand the immigration patterns of southern Louisiana and the cultures and histories of the individuals who still visit them. The pair collected oral histories and anecdotes from people they encountered during their cemetery surveys.

Both women also have a long-standing personal interest in cemeteries stemming from their childhoods. For Schexnayder, it comes from frequent visits to a family cemetery near her great-grandmother’s house.

“My cousin and I would walk down [to the cemetery], and I was fascinated by the names on the headstones,” Schexnayder said. “They were my relatives, and I wanted to know who they are, about what their life stories were, and I loved looking at the dates trying to figure out how old were they, and what did they do in their life.”

Manhein said her interest stems from the bygone practice of grave cleanings, an annual event common when she was younger during which families would return to cemeteries and tend to the graves of loved ones.

“It gave people the opportunity to share with others and their family, and maybe not in their family, about what had happened that year or two that they had not seen each other,” Manhein said. “It was a way of uniting communities together, keeping communities together, and you just don’t really see that much anymore.”

There are many things to be seen in Louisiana’s cemeteries, and much history lies entombed above and below ground. Schexnayder and Manhein visited the Chenière Caminada cemetery, which marks a part of Louisiana’s history before hurricanes were better understood.

“When we went down there to record what was and still is of the cemetery that is left there, it was a very eerie feeling because you know so many souls had been lost there,” Manhein said. “There’s a blank area out in the front of the cemetery that allegedly is a mass grave for people they could find, but hundreds of them were never found.”

The loss of coastal land in Louisiana is not a new phenomenon. Schexnayder and Manhein faced evidence of land loss during their travels. Schexnayder said they saw areas which were permanently inundated, had tombstones partially underwater or were already gone completely.

“It’s not if it’s going to be lost, it’s when it will be gone,” Schexnayder said. “We’re creating a digital record of that which can’t be physically saved.”

The goal of the Louisiana Endangered Cemetery Project is to preserve people’s connection to the past through “GPS mapping, photography, oral tradition and cultural artifact documentation.”

“I’d like to make this a call for other people to get out there and document,” Schexnayder said. “If they have a family cemetery, or if they’re interested in contacting us to put their cemetery in the list, we’d be willing to do that. I’d be willing to speak with them.”