Bathroom stalls across campus and the desks of Middleton Library are littered with swastikas, a symbol that may conjure up more images of human suffering than any other.

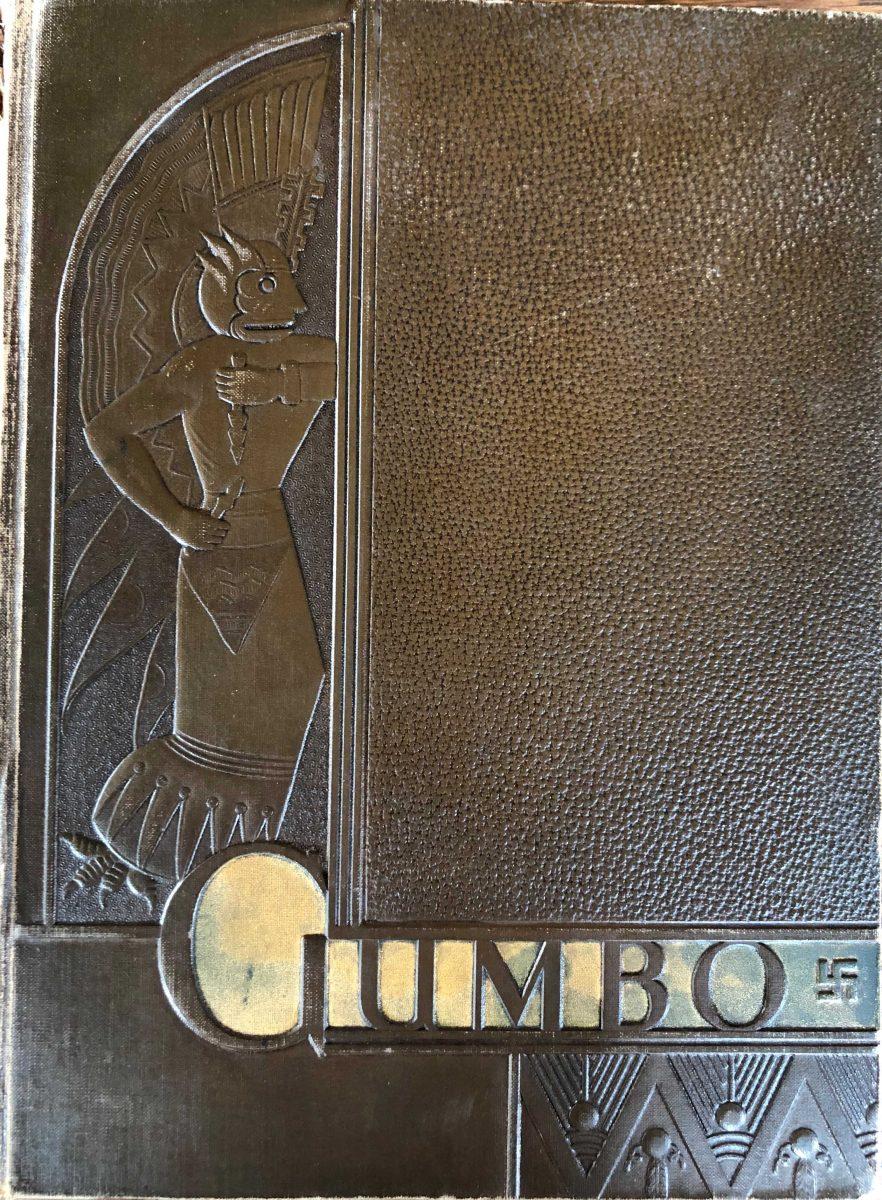

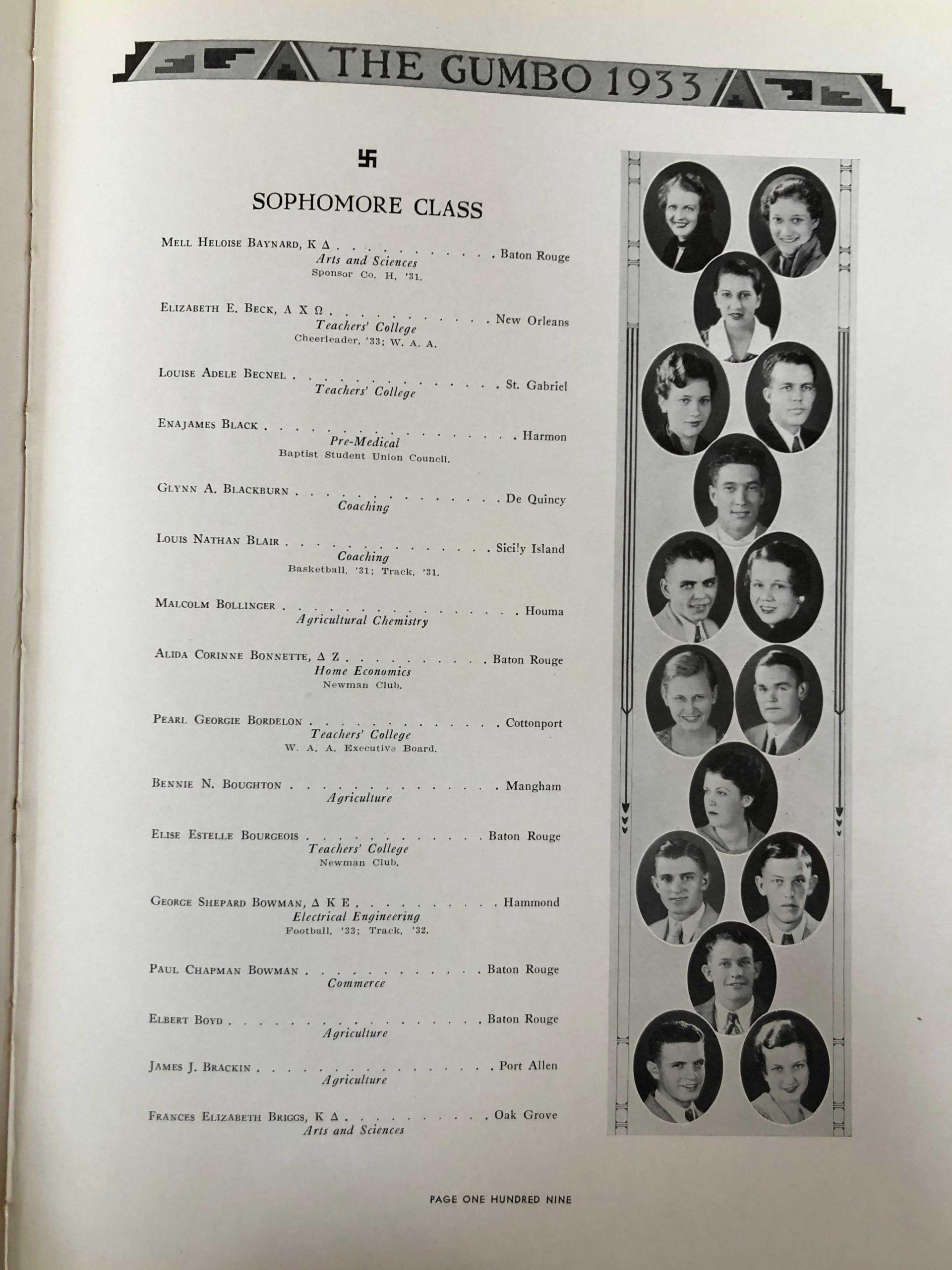

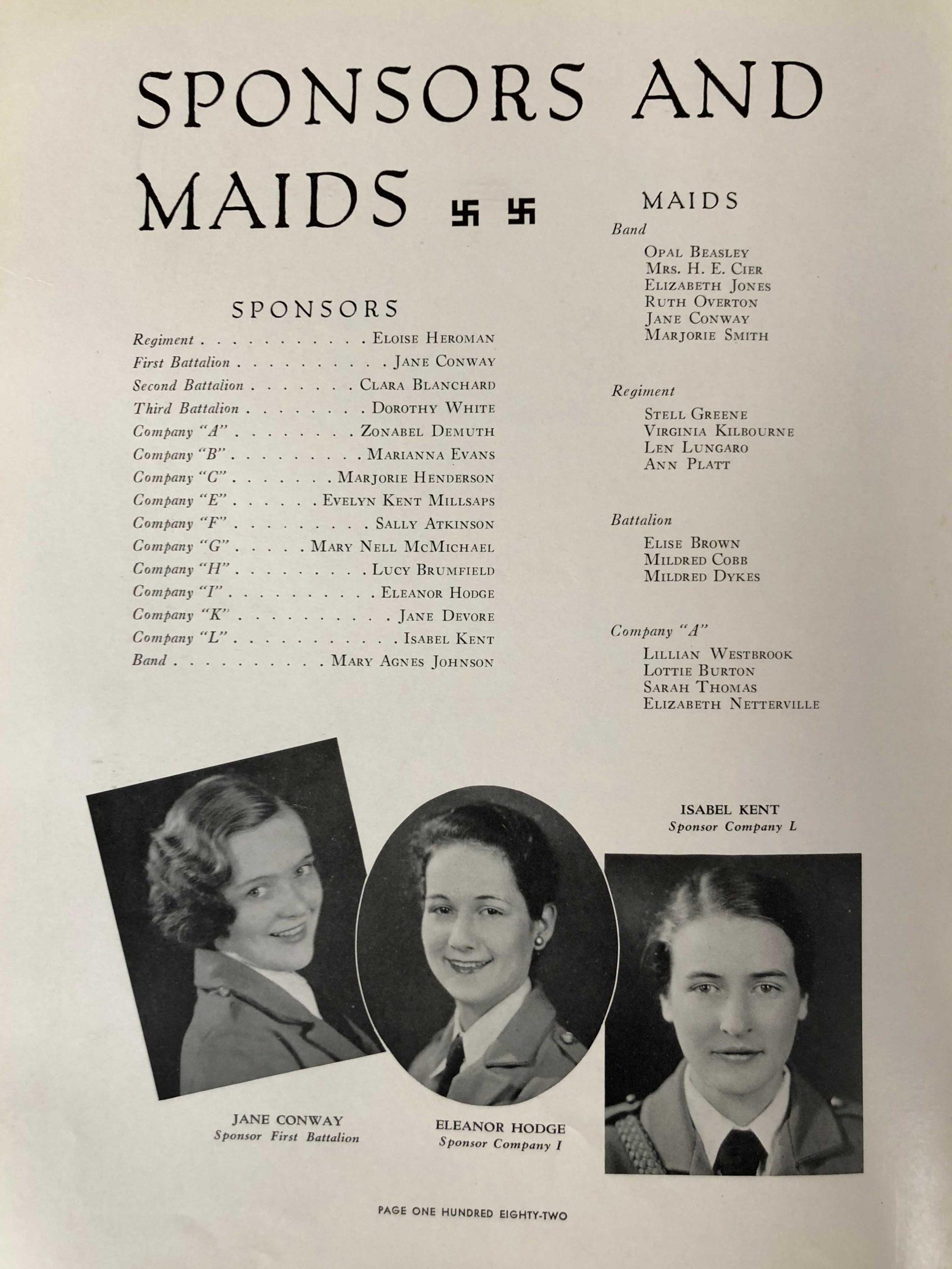

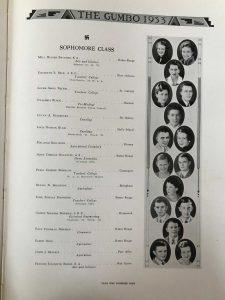

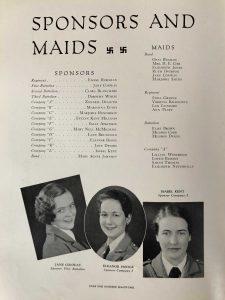

Beyond being crudely drawn images on forgotten desks, swastikas have an unexpected place in the University’s history — the 1933 Gumbo, unapologetically protruding from the yearbook’s hardcover and dotting every page alongside athletic teams and fraternity classes of bygone days.

Adolf Hitler seized the German chancellorship in March 1933. His Nazi Party blackened Europe with total war and ethnic cleansing, leaving Germany a divided land of smoldering debris and bomb craters. Despite this, the University’s 1933 yearbook heavily featured swastikas, the feared symbol synonymous with the Nazi Third Reich.

The yearbook’s theme was the ancient-Native Americans of the University’s burial mounds. Many Native American tribes throughout the Mississippi River Valley historically used the swastika to decorate objects like clothing and pottery before Hitler’s ascension to power.

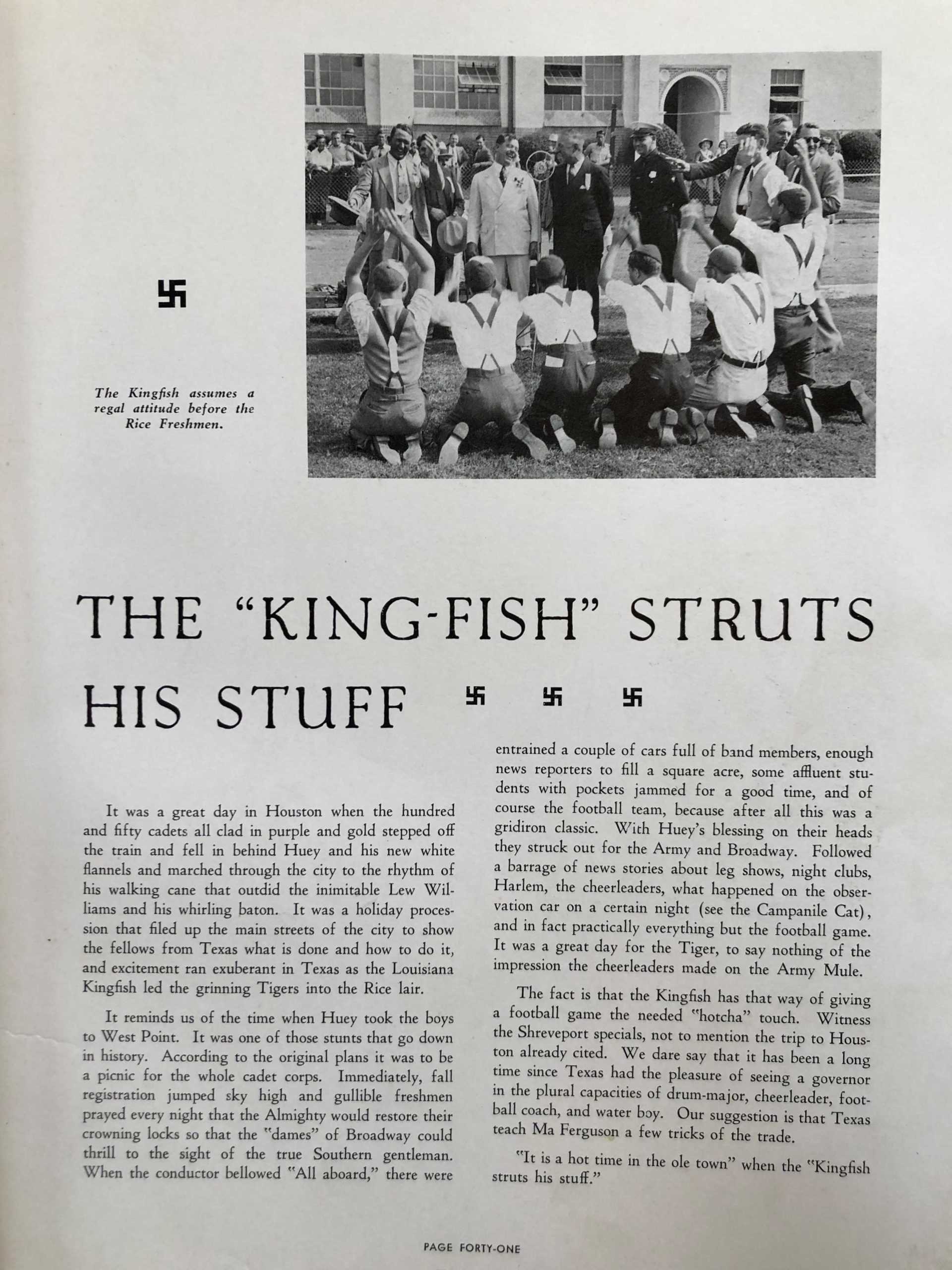

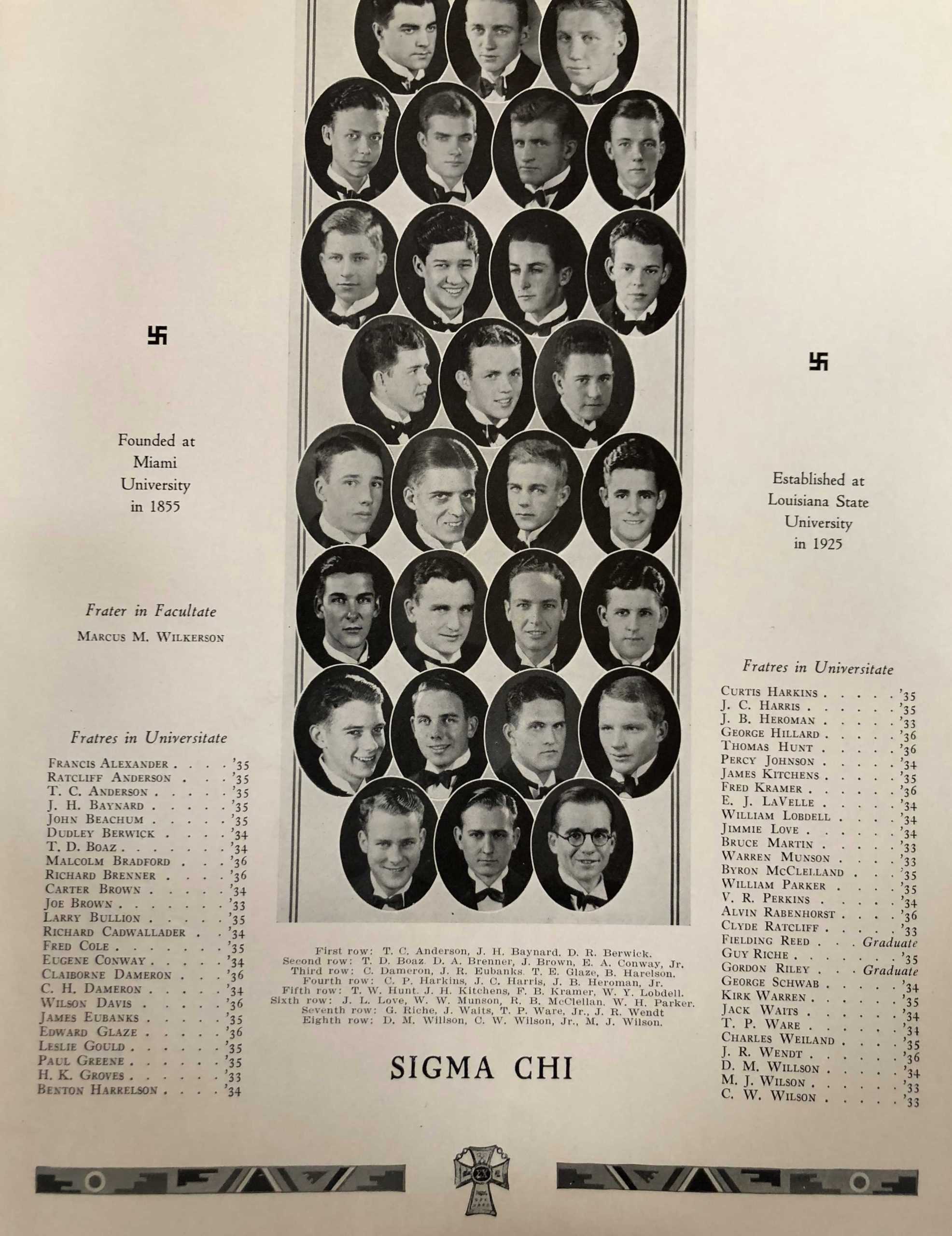

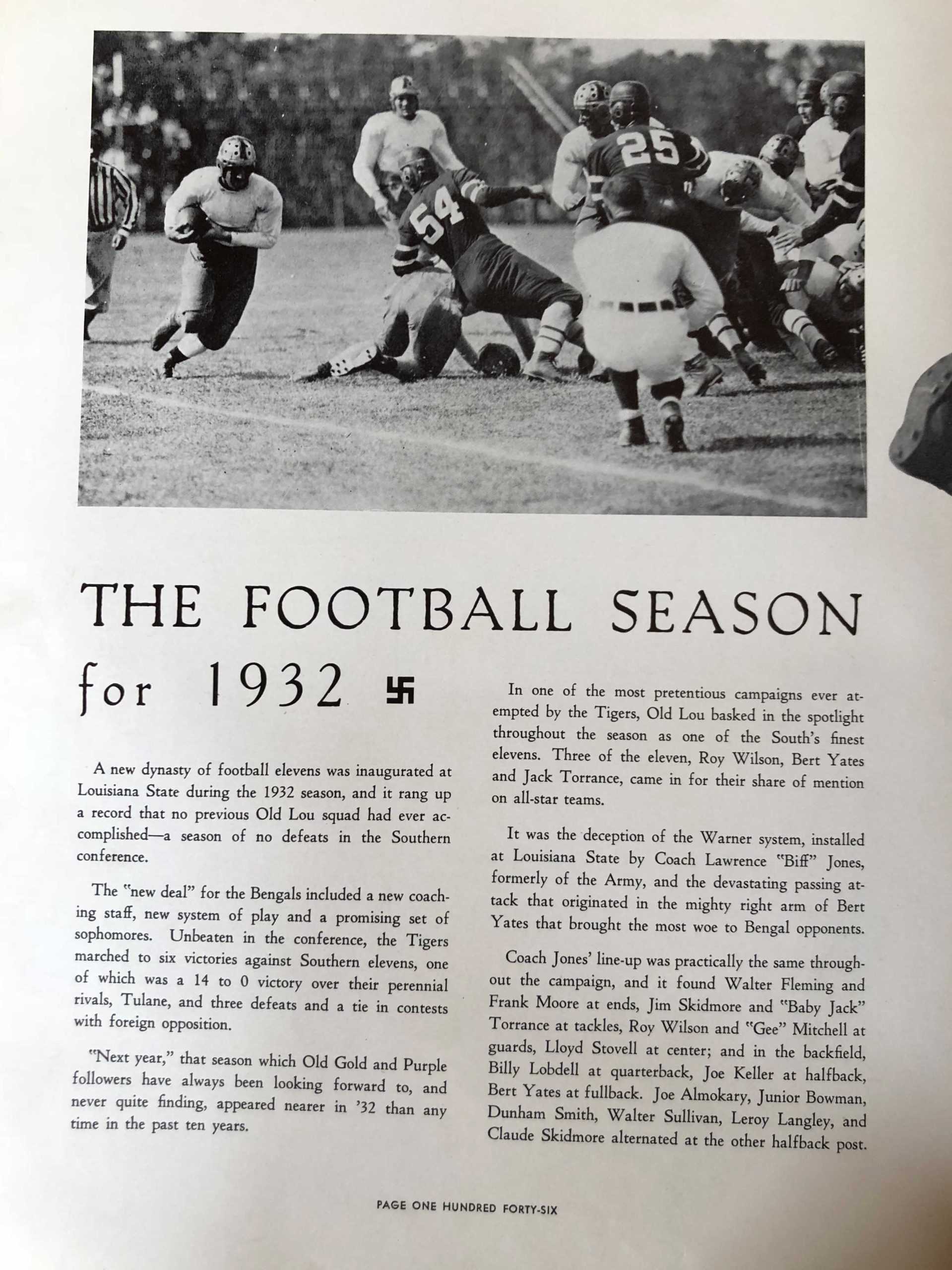

The Gumbo’s editor at the time, Marian Mayer Berkett, in a valiant act of defiance, kept the swastikas in the yearbook. Berkett, who was Jewish, would not allow Hitler to claim ownership of the symbol and re-appropriate its meaning. The swastikas did not endorse the Nazi Party, but paid homage to the University’s Native American ancestral roots.

“Because it really wasn’t the same symbol, I persisted,” Berkett said in an interview with LSU Libraries in 2004. “It was part of the artwork which I was trying to represent.”

Civilizations around the globe used swastikas before the Nazis. In Sanskrit, the word swastika means “well-being”. The symbol is commonly found in southern Asia, symbolizing eternal cycling in the Buddhist faith. Even the U.S. Army is not without the swastika’s presence. The 45th Infantry Division of the U.S. Army used a yellow swastika with a red diamond backdrop as its symbol until the 1930s.

“It was identified with other things besides Hitler,” Berkett said. “If you were to look at the artwork, there were other symbols used. Particularly on white pages where we needed a small symbol, we choose what turned out to be a swastika.”

Berkett’s grandparents descended from Alsace-Lorraine, the historically contested region separating Germany and France. Her grandparents immigrated to the U.S. to avoid being drafted in the Napoleonic Wars. After graduation, Berkett studied law at Tulane University and practiced for 72 years. Berkett died in June 2017.

Lost within the University’s lore, the swastikas of the 1933 yearbook offer students a glimpse at the Great Depression and the era of growing fascism in Europe. The persistence of a Jewish Gumbo editor kept the swastika on the pages and protected the sanctity of its symbolism — a symbol not of horrific murder, but a symbol of well-being and eternal cycling.

“You get the gut reaction of, ‘What in the world are there swastikas doing here?’” said political science associate professor Leonard Ray. “It’s a useful teaching device, though. You see it, and you’re shocked, but once you dig, you see the story take twists and turns.”