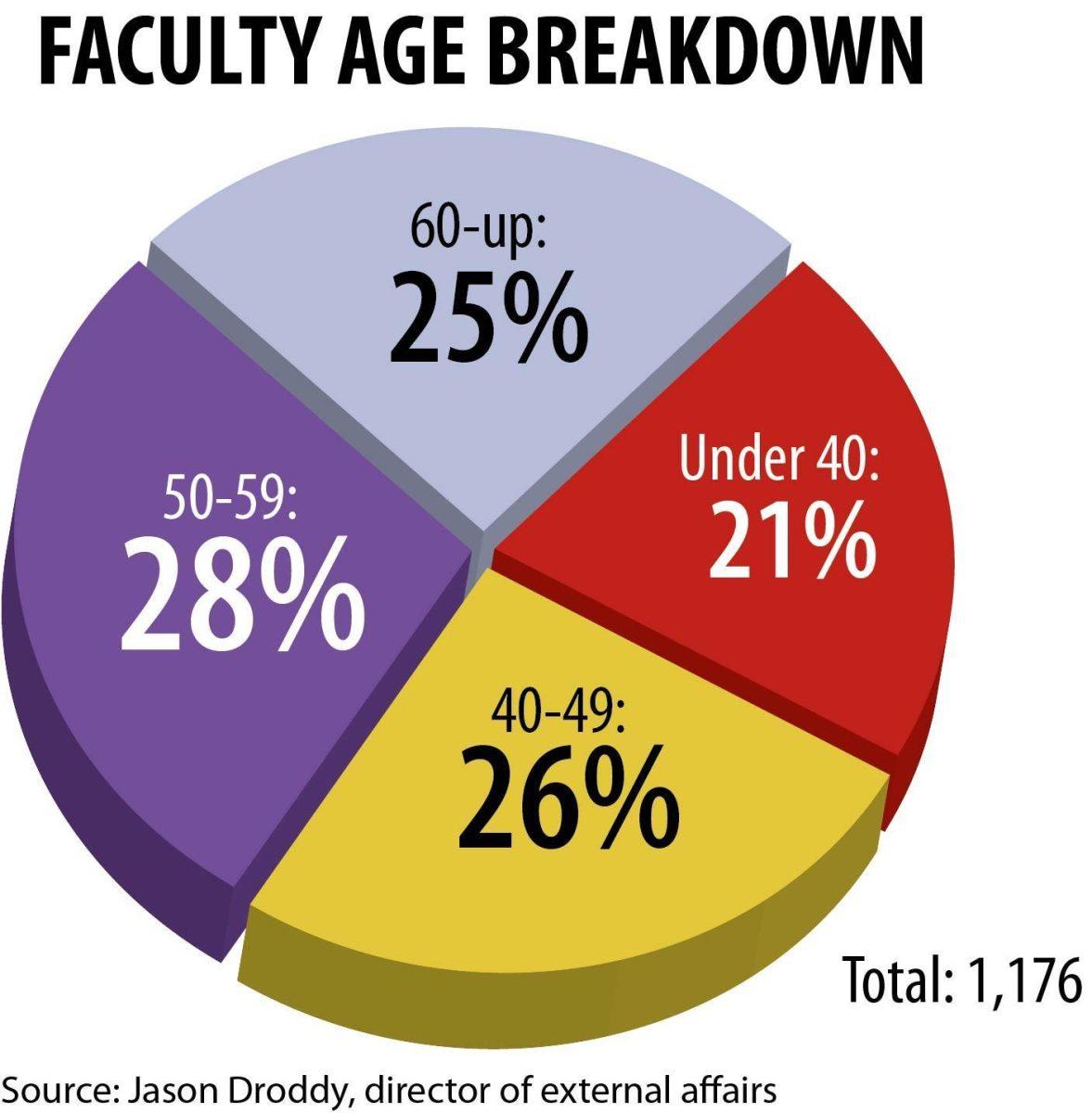

Chancellor Michael Martin said one of his primary concerns for the University is that retirement is looming for nearly 40 percent of faculty, while the amount of incoming faculty members has faded.

The University encompasses 1,176 faculty members, 468 of which are age 55 and older, according to Jason Droddy, the University’s director of external affairs.

Not only does this group boast strength in numbers, but older faculty members are usually the most experienced professors with considerable amounts of strong research, and they will leave en masse, Martin said.

“You’ll lose not only a large number [of faculty], but our most distinguished, most productive faculty, all at once,” Martin said.

Of professors aged 55 and up, 27 percent are 65 and older.

Universities spanning the country are seeing this problem, Martin said, while universities are also undergoing “salary compression,” when entry-level salaries begin nearing senior-level salaries because professors do not receive salary increases. In the past, the University could potentially fill two entry-level positions with the money from one vacant senior position, but that gap in salary levels has dwindled.

Solving this problem will mean collapsing more programs to create efficiencies, increasing the University’s endowment and spiking tuition and fees, Martin said.

Kevin Cope, president of the University’s Faculty Senate, said the first half of the baby boomer generation — those born between 1945 and 1955 — have bolstered universities as educators for generations, but the second half of baby boomers — those born from 1955 to 1972 — did not join the first half in their educational pursuits. Now, the retiring generation has not cultivated its succession, Cope said.

The University also has a backlog of 136 endowed professorships because the Louisiana Board of Regents lacks the money to fill professor endowments, Droddy said.

Martin said if University professors can gain those endowments, they would bring prestige to the academic field.

“There are fewer people going into the academic vocation,” Cope said. “Strictly speaking, the academic career is the best career that there is. But the quality of academic life is valued.”

Government policies also play a role in the academic profession, Cope said, as it is the University’s responsibility to educate its lawmakers about the importance of funds for education. He said the University spends its time treading water to stay alive at the state funding level, but faculty members should be talking to legislators, and legislators should come to the University and see the inner-workings of academia.

Cope said universities need to open more avenues for people who work there, giving professors the ability to shift between areas and departments.

Another way the University could stress educational importance is to return to its old mission of educating the public, Cope said.

He said the University of Arkansas’ chancellor has a weekly TV spot in which he discusses education. Administrators could also underscore the importance of traditional University disciplines because people may question their values if administrators do not hold degrees in those disciplines, he said.

Biological sciences graduate student Kelley Gwin said people generally have three avenues of pursuit in the sciences — industry work, government work and academics. Academics, she said, gives the most freedom for research and the ability to teach.

Gwin said the main hiccup for people entering advanced degree programs in the sciences is funding problems because researchers must have funding from outside organizations, such as the National Science Foundation, which are also facing budget shortfalls.

“If funding were easier, you would have more influx in academics,” she said.

But Kristopher Mecholsky, English graduate student, said graduate students in the humanities are seeing the opposite problem.

“The job market is such that if you’re graduating with a dissertation, you’ll spend years finding a job,” he said.

Mecholsky said there are too many students seeking advanced degrees in the humanities to fill too few positions, but it does not detract him from pursuing a career as an English academic.

“I still believe in the life of the mind. This is what I want to do,” he said. “I don’t care how hard it is right now — I’d still be here regardless of the job

Chancellor worries about losing nearly 40 percent of faculty to retirement

September 29, 2011