When it comes to racial divisions, American society has proved itself to be a dichotomy between white and black. It’s a fact that makes minorities perpetually feel like outsiders. As a second-generation immigrant, I can attest to the fact that the American experience includes the pressure to assimilate while simultaneously balancing the values of my parents’ culture.

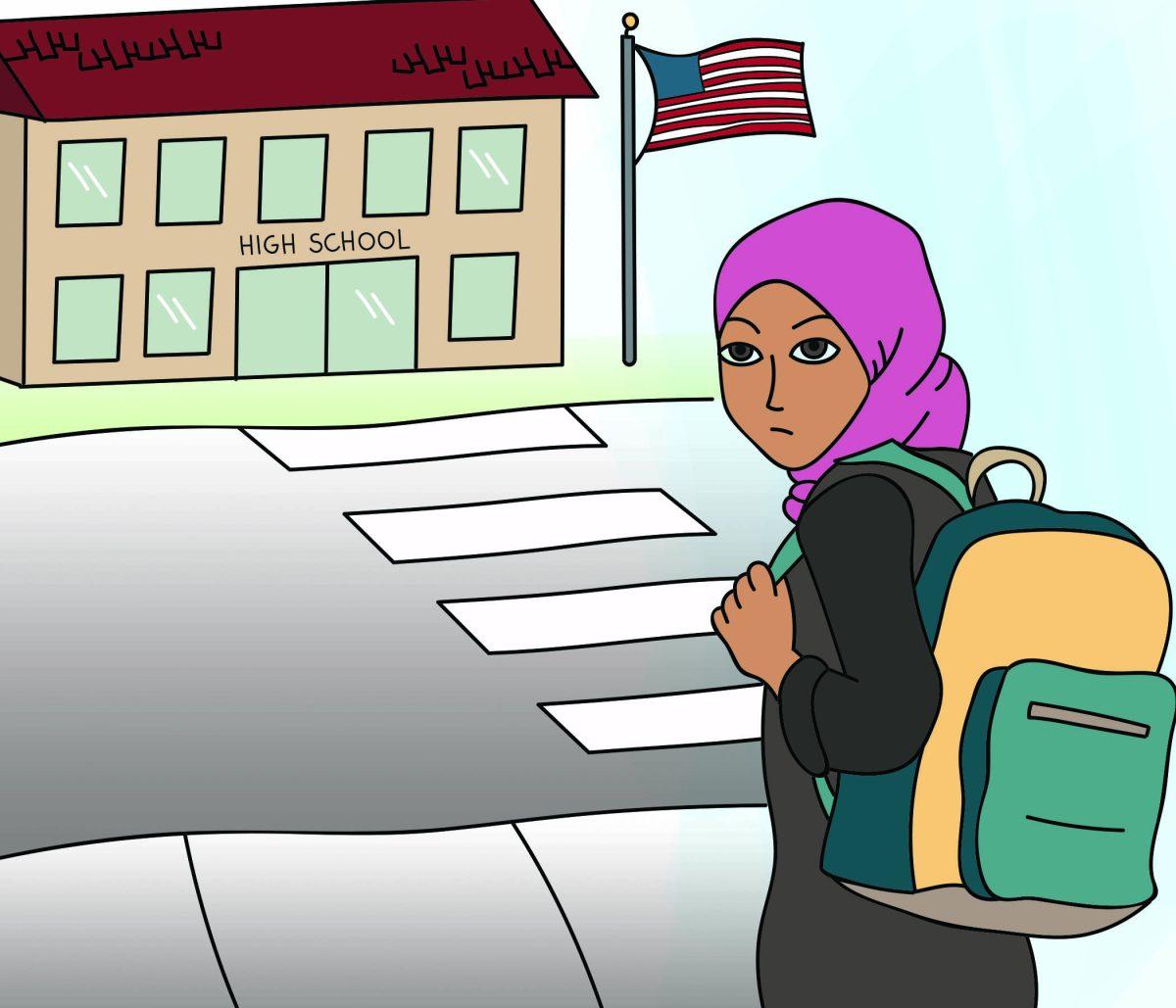

This is similar to the feelings tens of thousands of first-generation refugee teens from the Middle East and Africa who have have been granted residency in America experience. They’ve fled persecution and violence from Iraq to Kenya to Syria, and they feel the United States is a place of opportunity for themselves and their children.

Since I was a child, my parents instilled the idea in me that America was the “land of opportunity,” where you could achieve anything if you worked hard enough.

Immigrants from developing countries or refugees seeking asylum often have different stakes than their natural-born peers. We spend our whole lives making something from nothing so all the suffering before that point was worth it. We aim to be more educated than our parents in order to get high-paying jobs so our families will no longer be struggling.

This creates a difference in work ethic between natural-born and naturalized citizens. Minority work ethic is also driven by the pay gap that exists between the races, which only makes the struggle to build a foundation in this country harder. It usually leads to a cycle of poverty that makes the poor poorer and the rich richer.

The New York Times ran a feature earlier this year on refugees who were high school seniors in Boise, Idaho. Their stories and experiences exemplify the transition of foreign teenagers and their perspectives on fitting in with their peers. It is obvious there is a distinction in morals between the Americans and the refugees.

One refugee, an 18-year-old named Muganza Katanga, lived in a camp in Rwanda for seven years. He says his mom fought to make sure they ate every day, which he said is how he got the mentality that, “Everything is right in front of you. All you have to do is go there and get it. It takes hard work. It takes a long time. But you just have to be patient and know how you’re going to get it.”

Another refugee earns his wages by working as a janitor for five hours a day at $8 an hour, in addition to attending soccer practice each day to ensure he keeps his scholarship. He often can’t do homework because he gets too tired.

A Hispanic coworker of mine once told me she could tell as soon as she had children in America that it was going to be an uphill battle. She was trying to teach the same values of education and hard work to her children that were taught to her, all while they were going to school and unlearning those values from peers of higher privilege. It puts immigrant teens at an awkward crossroads of wanting to conform and imitate their classmates while staying completely focused on school, regardless of the social consequences.

Feeling like an outsider is a constant social consequence I personally face. It wasn’t until I got much older that I realized that America’s “melting pot” didn’t necessarily have a positive connotation. The obvious bilateral racial war makes it impossible to blend into our surroundings from the beginning, just because of the color of our skin.

I used to wish I could melt into the walls when people asked me insensitive questions about my culture, even if their intentions weren’t malicious. It’s the constant reminder that you are an alien, a visitor, and you will never reach normalcy.

Assimilation feels like I’m splitting myself in half to be acceptable on both sides of my life. You edit out the confusion when people make references you don’t understand, the inferiority complex that comes with being surrounded by American nationalism and the subconscious stereotyping from even your closest friends who try to understand but never will.

Over time, you find a way to accept living in two different worlds without ever really belonging to either one. The “land of opportunity” comes at great cost, but sacrifice is the trademark of the immigrant lifestyle. Our parents sacrifice for us, and we sacrifice for them and our children and hope that one day all of the suffering pays off.

Anjana Nair is an 18-year-old international studies sophomore from Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Opinion: Immigrants struggle to find balance between values, pressure to fit in

By Anjana Nair

October 12, 2016