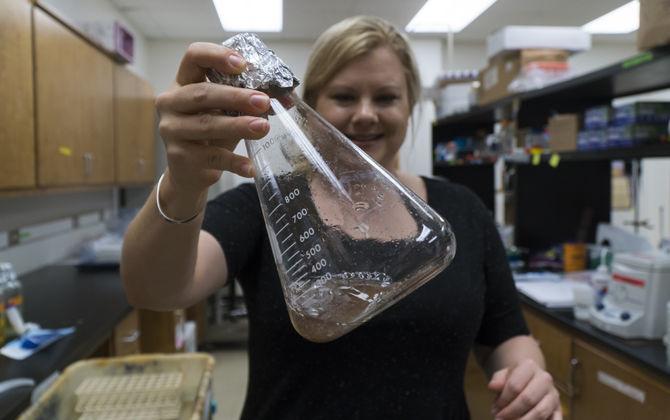

Noelle Bryan researches bugs in space.

Bryan, a biological sciences Ph.D. student, has been researching and identifying the bacteria, or “bugs” as she calls them, surviving in the stratosphere as high as 36 kilometers since 2009 as part of the MARSLIFE project.

MARSLIFE is an acronym for Modes of Adaptation, Resistance and Survival for Life Inhabiting a Freeze-dried-radiation-bathed Environment.

“We wanted to go back and be able to do multiple samples and verify with multiple measurements that there are microbes and things out there and determine if they’re alive — and if they’re alive, who are they and how are they surviving up there,” Bryan said.

She said microbes are captured in a high-altitude balloon and automated mechanical device designed by a team of undergraduate students each year. The variety of students who participated in the creation of the device ranges from electrical and mechanical engineers to design students.

Bryan has consistently worked with adviser Brent Christner, an adjunct faculty member in the LSU Department of Biological Sciences and research professor at University of Florida, physics and astronomy professor T. Gregory Guzik and Space Science Research Group researcher Michael Stewart.

NASA’s Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research and the Louisiana Board of Regents funded the project.

Bryan said the project is unique because it is attempting research on bacteria higher in the stratosphere than any other place in the country.

The purpose of sending microorganisms into the stratosphere is to record and discover the ceiling height of altitude these organisms can survive in stressful conditions, as well as to identify how they change when brought back down to Earth in the lab, she said.

Bryan hopes to actually send the microorganisms to Mars one day.

“It’s a very challenging environment,” she said.

In the stratosphere, environmental conditions including pressure, temperature and radiation levels, are similar on Mars.

Bryan said microbes are measured using microscopes that count the total number of bacteria cells, as well as dust particles and other items found beyond the atmosphere.

The microbe capture device looks like a simple metal box, but is much more complex.

Bryan said the device has two chambers on each side that open at a target altitude. Inside each chamber, bacteria are caught with small sticky rods. Once the device reaches the desired altitude, it seals and returns to Earth.

“I think we’ve laid some really important groundwork for hopefully other people to maybe start giving attention to atmospheric microbiology — that maybe there is a reason to look at higher altitudes and maybe not just limit research to the first few kilometers of Earth,” Bryan said.

Student with MARSLIFE program studies bacteria survival in stratosphere

September 13, 2016

University graduate student Noelle Bryan researches microbes and their reaction to life on Mars by utilizing Earth’s stratosphere as a similar environment in her project, Modes of Adaptation, Resistance and Survival for Life Inhabiting a Freeze-dried-radiation-bathed Environment, or MARSLife.

More to Discover