With the discovery of a new species, post-doctoral fellow Sara Ruane is helping define the evolutionary patterns of snakes in Madagascar.

In February 2014, Ruane and a team of researchers from the American Museum of Natural History and the Université de Mahajanga in Madagascar discovered a new snake species in Madagascar’s Ankarana Reserve. The team named the species Madagascarophis lolo, derived from the Malagasy word for “ghost,” because of the snake’s distinctive pale gray coloring and elusiveness.

On Sept. 1, the team published its findings in “Copeia,” a scientific journal dedicated to the study of fish, amphibians and reptiles. The article detailed lolo’s alternating light and dark grayscale pattern, smaller, gracile body type and genetic relationship to other species in the same family, Ruane said.

Ruane focused largely on the snake’s genetic composition, comparing the ghost snake’s DNA profile to other snakes in the same genus. Lolo’s nearest relative in the Madagascarophis genus was only discovered in the last three years, she said, possibly indicating the snakes are specific to the northeast of the country.

Like many scientific breakthroughs, the ghost snake’s discovery happened by accident.

The overarching goal of the two-month expedition was to capture and collect DNA samples from about a dozen predetermined rare snake species, Ruane said. After an unsuccessful weeklong mission in Ankarana, heavy continuous rain forced the team to abandon its search and focus its attention on other areas of the country.

Before returning to camp, the team explored an under-surveyed path near the park entrance that traverses an area of sharp limestone “tsingy” rocks, meaning “where you cannot walk barefoot,” in Malagasy, Ruane said. Malagasy master’s student Bernard Randriamahatantsoa captured the ghost snake while on the path.

At first, the team gave little consideration to the discovery, she said. The Madagascarophis snake family is common in the country, and the discovery didn’t create much initial interest.

It wasn’t until the team conducted further morphological analyses and genetic studies that it realized lolo was considerably different from members of the same genus, Ruane said.

She said lolo’s discovery illustrates Madagascar’s biodiversity and proves the importance of continued study and species surveys.

“The thing that’s most important about it isn’t necessarily the species itself, but that it really illustrates that even among these really common snakes, there’s still this hidden diversity that we don’t know about,” Ruane said. “It just goes to show that even in a moderately well-explored area like Ankarana, you don’t know what’s out there.”

Frank Burbrink, the associate curator of amphibians and reptiles for the American Museum of Natural History, said there are 3,500 species of snakes identified worldwide, but it’s possible the true number is closer to double that. Lolo’s discovery is one piece of a much larger, complex evolutionary puzzle, he said.

“There are many, many more snakes to be found,” Burbrink said. “If you think about it in the old record days, this is a top single, but the record is going to be coming out soon.”

Madagascar is a hot bed for biodiversity and speciation, providing scientists a living laboratory for the study of evolution, he said. Many of the species on the island are endemic to Madagascar, including 99 percent of snakes on the island.

The rarity of the island’s species means their identification and conservation is especially important, Burbrink said. Oftentimes scientists don’t know evolutionary gaps exist until the missing links are discovered. When species die out before discovery, it makes it more difficult to trace the evolutionary processes, he said.

Madagascar’s habitats are suffering from deforestation because of the spread of agriculture and the native population’s need for charcoal. Researchers’ continued discovery of new species is critical for conservation, Burbrink said.

LSU fellow part of team which discovered new snake in Madagascar

September 13, 2016

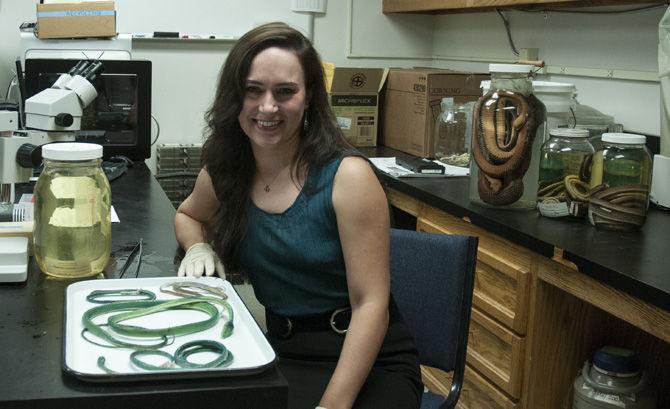

A snake species is held in a bucket for further examining on Sept. 13, 2016 in Foster Hall.

More to Discover